After 10 years as a busy missionary priest in Africa, I was driven to spend some time in silence, prayer and solitude. I had spent three of those years in Nigeria, witness to unspeakable horrors and atrocities during its civil war. Delivering aid was a matter of life and death. Once, in 1972, at a checkpoint on a jungle road, a group of drunken soldiers stood me up to be shot. Only my ability to speak a local language saved me and the others in my group. I didn’t just feel I wanted to seek respite; it was something I knew I must do. Nor did I know where it would lead or for how long, but I imagined it would be for a week or two. So I asked my Father Superior for permission, then wrote to the abbot of a Trappist monastery in Portglenone, Northern Ireland, asking if I could become an “instant monk” in his community. He agreed, and Father Jim, the novice master, became my mentor and guide.

I fit easily into a daily schedule of prayer and study, work and sleep, each marked by the sound of a bell. My body, however, needed time to adjust to the new regimen of going to bed at 8 p.m. and rising at 2:45 a.m. to attend prayers 15 minutes later.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

I entered deeply into the spirit and rhythm of the place and even learned a little of the Trappist sign language the monks used to avoid speaking. But instead of bringing me silence and solitude, the busyness of the monastery felt noisy. My spirit was calling for something else.

The monastery sat on about 120 hectares of pasture, where Brother Colum managed a herd of hundreds of cattle, a main source of the community’s revenue. It housed 38 monks and a hermit, Father Kevin, who lived in a small caravan hidden in a wood. Father Kevin, tall and bearded, arrived each Sunday to celebrate mass with us and share the main meal, all in silence. Likely in his late 40s — more than a decade older than I was — he’d been a hermit for about 17 years.

I knew I needed a spiritual guide, so asked the abbot if Father Kevin might agree to act in that role. “You can certainly ask,” he said, “but it’s highly unlikely he will agree. He has always refused such requests.”

Father Kevin, skinny and tanned from working outdoors, looked surprised as he opened the door. “Come on in,” he said softly, then added almost apologetically, “I only have one chair, so what if we both sit on the floor?” The place was sparsely furnished but orderly and very clean. “I saw you in the cloister a few weeks ago and wondered who you were,” he murmured.

I wasn’t sure how to begin. I explained why I’d come to the monastery, that I had no idea how long I would stay and that a spiritual hunger was drawing me deeper into a world of silence and reflection. I spoke for more than an hour.

“Why don’t we pray together for a while,” he said and, without waiting for me to answer, moved to the end of the room, where he had a small altar with a tabernacle in the centre covered in colourful Gaelic designs. He squatted on the floor in front of it, and I sat beside him. I’ve no idea how long we prayed in silence since neither of us was wearing a watch; I’d removed mine the day I arrived. The monastery bell rang in the steeple, signalling that the choir monks would be going to the chapel to recite their short mid-afternoon prayers. Father Kevin got up to retrieve his prayer book, and together we recited the Psalms.

“Michael,” he said, “I think the Holy Spirit is telling you something, and you need to respond. I suggest you ask the abbot if you can live in the small hermitage near the river and see where the Lord leads you. I feel certain your vocation is not that of a hermit, but, just like the Lord, you may be called for 40 days into the desert.”

I was shocked. “But even if he approves,” I responded, “I’m sure he’ll want some assurance that I meet with a spiritual director regularly. What should I say? You’re the only person I’ve spoken to. Will you be my guide?”

Father Kevin took a long pause. Then, speaking hesitantly, he replied, “First of all, Michael, I’ve nothing to offer you; I, too, am searching. Tell him if he agrees, we will meet and pray together for an hour each week.”

So, armed with a small library of books (I was interested in Eastern Orthodox spirituality and intended to do some research), several notebooks, a collection of spiritual and educational cassette tapes, a stack of magazines, a stock of food and a few sets of clothing, I headed out across the fields to my hermitage.

It was a small wooden shed, just over three metres square, with a tiny window, a one-ring gas burner for cooking, a simple wooden table, a small electric lamp, a plug for my tape recorder, a chair, a prayer stool and a wooden bunk bed. In one corner were three narrow shelves for my clothes, and hooks to hang my working clothes and religious habit. The River Bann was just 15 metres away.

I divided my day into three parts in the traditional way: prayer (meditation, spiritual reading, religious study) for eight hours, manual work for seven, sleep for seven and food preparation and other tasks for two. I drank black tea or water and ate twice a day. My main meal was a hearty vegetable soup.

Since I could hear the monastery bells throughout the day, I always knew what time it was. At night, a single bell rang inside the monastery to wake the monks but not people in the surrounding villages or me. I borrowed a small alarm clock so I, too, could get up for the first prayer of the day. After celebrating mass on my own at 7 a.m. and eating a light breakfast, I began my manual work.

I had arranged with Brother Colum to work on the farm. That meant cleaning ditches, seemingly by the mile, trimming and laying hedges, repairing fences, building new ones, installing fence posts, planting trees, scything weeds and any other work he required. Every day I dressed for work, hiked across the meadow and checked my message box for work instructions and tools if needed. Every night, once the monks had retired, I walked to the monastery, took a shower and replenished my supplies. An hour later, I, too, was in bed. I met with Father Kevin every Friday for an hour. On Sundays, I attended community mass and joined in the silent midday meal. With no manual work that day, I wrote letters, prayed and studied.

The hut had no insulation and could get bitterly cold at night. I needed not just extra blankets but also a thermal sleeping bag. I slept wearing two T-shirts and a sweatsuit. On winter mornings, I lit the gas ring to warm up the hut, just so I could function. After years in Africa, my body was simply not attuned to the Irish seasons. Working outside, I was warm enough in a heavy parka, beanie and thick gloves.

I began my hermit’s life in early February. The naked trees and the tilled land, often covered with hard frost, created a sense of peace. I enjoyed the quiet and the solitude and went to bed each day tired but content.

On day six, something happened. I was walking in a field, trying to pray the rosary, when my head seemed to explode with noise and interruptions. Gone was my new-found tranquility. I was bombarded with thoughts, images and all kinds of distractions, both holy and profane. Intuitively, I knew what I needed to do. I gathered my library of books, cassettes, magazines and articles and everything not essential and stashed them in my cell back at the monastery. I kept just two books: New Seeds of Contemplation by the 20th-century Trappist monk Thomas Merton and a French edition of L’Abandon à la Providence divine (Abandonment to Divine Providence) by the 18th-century Jesuit Jean-Pierre de Caussade, which had made such an impression on me when I was a novice.

I shared my experience with Father Kevin, who nodded and said: “God calls us to silence and solitude, and we want to fill that precious time with noise and distraction, albeit with seemingly religious and holy things.” Then he quoted Merton: “Every one of us is shadowed by an illusory person: a false self. This is the man I want myself to be, but who cannot exist, because God does not know anything about him. And to be unknown of God is altogether too much privacy.”

As my prayer life deepened, so did my self-awareness. I was acutely conscious of the presence of God in my life while realizing my body, mind and emotions were pulled in a different direction. I felt like two different people. I craved food when I wasn’t hungry; I wanted sleep when I wasn’t tired; an inner voice urged me to cut down on meditation and prayer even though my purpose was to maintain both. At times, I wondered if I was just playing at being a hermit.

Father Kevin gave me the perspective I needed. “We’re not very good at recognizing illusions, least of all the ones we cherish about ourselves. Contemplation is not and cannot be a function of this external self.” I bared my soul as we prayed together, and he gently guided me. “Prayer and love are learned in the hour when prayer becomes impossible and the heart has turned to stone,” he said one day as we discussed contemplation. And in helping me understand my call to the hermitage, he explained: “In silence, God ceases to be an object and becomes an experience.”

Days were turning into weeks and weeks into months. I had no expectations, no plans. I was simply trying to live each day. I knew I was in the right place.

And then something else happened.

It was a cold, blustery night, raining hard. I was trudging back to the hermitage after my shower. The manual work had been particularly demanding that day, and I craved sleep. With my parka zipped up to my chin, my hoodie pulled on tight and my backpack slung over my shoulder, I leaned into the driving rain. I can’t remember what was going on in my head, whether I was daydreaming, trying to pray or just grumbling to myself about the weather when an interior voice — as clear as if the person was next to me — simply said: “I am with you, Michael.”

I stopped and straightened up, riveted by the sense of this somebody, someone around me, next to me. I knew who it was. It was an old friend I had spoken to for years, but as if from a distance. Now he was here. “Jesus,” I said.

I have no idea how long I stood there in the pouring rain. I was filled with a sense of peace that I had never before experienced. Tears of joy mingled with the rain streaming down my face. Back at the hermitage in dry clothes, I just wanted to revel in the warmth of his presence. I kneeled on my prayer stool, transfixed. Meditation became contemplation as I basked in the sunshine of God’s spirit. I didn’t need any words, scripture or spiritual reading to lead me into God’s presence. I did not want to leave. But eventually, my exhausted body took over. I went to bed, wondering if this extraordinary spiritual experience would be gone by morning.

- 10 spiritual hikes to rejuvenate your soul

- A pilgrim seeks meaning on St. Cuthbert’s Way

- This couple embarked on a 28,000-km journey across Canada and haven’t looked back

I tried to follow my usual routine, but it had all changed; the experience of my prayer time and celebrating the eucharist were different. I was simply aware of a presence that radiated love. It seemed almost to be within me, to envelop me. I didn’t want to do anything other than pray; I no longer needed my faith. God was real. God was an experience, just as Father Kevin had prophesied.

As I started my manual labour that day, clearing several ditches that had been blocked by a storm, I only had to pause for a second to be reassured I was not alone. At one point in the afternoon, when I was still removing fallen limbs and debris, a voice seemed to say: “Stop what you’re doing. I want to talk to you.” So I stopped and walked slowly up and down alongside the hedgerow, back and forth for what seemed like half an hour, locked in God’s presence. We were beyond words. My heart felt as if it was ready to burst with God’s love, the two of us simply connecting, becoming one. Only the monastery bells brought me back to earth. Although I did not feel hungry, I knew I needed to follow my schedule and fix my main meal of the day.

As I prepared my food, doubt began to enter my head. Am I having a psychological breakdown? Is this solitude getting to me? I needed to talk with Father Kevin, but that would not happen until the following afternoon.

“God works in mysterious ways; the Spirit breathes where it will,” Father Kevin counselled with his usual brevity. “Let’s just pray about it and come back in three days or before if you are troubled. Meanwhile, just follow your normal routine.”

I didn’t want to do anything except spend time in contemplation, but I did what Father Kevin suggested. “You are blessed with an experience of God, Michael, and it will change you forever if you allow it. It is powerful and vibrant, but it will not last. Only the Lord will show you when the Lord will withdraw from you, and then you will have to rely solely on your faith and your memories. That might happen in a day, a week. Only God knows. And be assured, you are not going out of your mind!”

As the seasons changed, so did my prayer life. For eight months, I was privileged to enjoy an extraordinary experience of God’s presence that was as real as the air I breathed and the land I walked. But in the late fall, my meditation shifted subtly. I continued to enjoy the stillness and solitude of the hermitage, but my contemplation was no longer immediate. I didn’t feel God’s presence constantly, as I had in the early days. I began to struggle again with distractions, but understood this was a return to normal life.

Now I had to exercise the new-found faith I had been given. I felt an impetus to share my experience, a call to help others. It was a gentle whisper at first, but an unmistakable voice. I listened to it for several weeks, then one Friday, after we had shared our prayer time, Father Kevin simply announced, “I think it’s time, Michael. The Spirit is calling you back to ministry.”

I’d been in the monastery and my hermitage for almost 11 months.

***

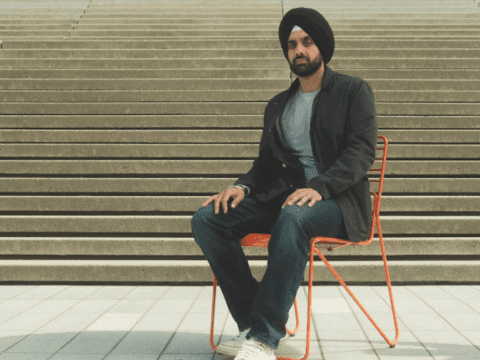

Michael Barrington is a writer of novels, short stories and essays. He lives near San Francisco.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “My Year as a Hermit.”