Mumilaaq Qaqqaq was elected as the member of Parliament for Nunavut in October’s federal election. She’s since been named the New Democratic Party’s critic for Northern Affairs and the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency, as well as deputy critic for Natural Resources. She spoke with Alex Mlynek.

Alex Mlynek: What is your biggest priority for Nunavut?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Mumilaaq Qaqqaq: To get basic human rights for those in my territory. Clean drinking water, lower living costs and tackling housing issues.

I find we talk a lot about opportunity — but how can anyone expect someone to be able to live to their full potential if they don’t even have their basic human rights? So that will be my focus over my term.

AM: At 26, you’re a reflection of the demographics of Nunavut, where two-thirds of the people are under 35. What are young Nunavummiut calling for?

MQ: Aside from basic human rights, the availability of child care needs to be improved, as do post-secondary opportunities in our territory so that we don’t have to leave to pursue education. Housing is another huge one with growing families. Lowering living costs, creating job opportunities.

And for the next generations to be able to thrive, we need to be given control over what happens in our communities.

AM: The other big challenge is the climate crisis. What effect has that had on Nunavut?

MQ: That’s definitely a concern. We see migration change. With the colder season shortening, we see polar bears not able to be on the ice for the time they should be, so they wander into town. We see an increase in seals in our waters.

And then we have a bunch of people down south telling us that we shouldn’t kill the cute little seals or the majestic, wonderful polar bears, when in reality, seals are a source of income and a source of food that help with the high living costs. And polar bears are a threat to the safety of individuals in our communities.

We’ve also seen sinkholes. We’ve seen permafrost starting to melt, which affects our infrastructure, our buildings.

We see it in so many ways. So even though we don’t see the big factories that are polluting, and we don’t see masses of garbage in our waters yet, we’re being directly impacted. And it’s unpredictable, which is the scariest part.

More on Broadview: Sheila Watt-Cloutier on the disappearing Arctic

AM: You grew up in Baker Lake, Nunavut, and now live in Iqaluit. What do you love most about your home territory?

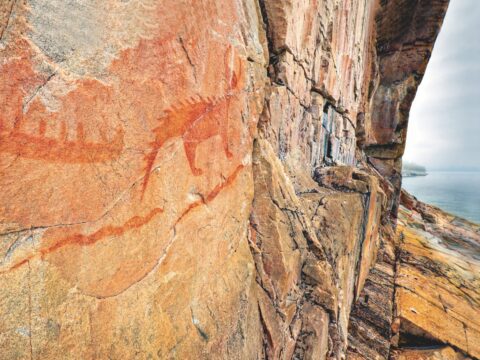

MQ: Everything. The people, our lands, our animals. My brother is a full-time hunter-trapper, and last spring, I walked into my mom’s and there was a fox pelt and a wolverine pelt hanging there. Then, when I walked into the furnace room, there was a muskox carcass. I usually help my brother with the butchering; being able to pack meat and butcher meat, that’s home to me.

And no trees, honestly, is one of my favourite things. We’re in a place where we can see oftentimes for a very far distance. To me, that’s comfort. I’ve lived in P.E.I., in Peterborough, Ont., and in Ottawa, and I didn’t like living around trees and tall buildings.

And I love the fact that we don’t knock here; when you’re at someone’s house, you just walk in. We sit on the floor, we eat our country food on the floor, and that’s what makes sense to me. There are a lot of things that may seem small to other people, but they’re big things to me.

AM: There’s also the language. What does Inuktitut mean to you?

MQ: I’m half Danish and half Inuk, and I’ve decided to take certain parts of both those aspects. But I lean much more to being Inuk and those values and beliefs.

My brain thinks in Inuktitut, but I only speak in English, and Inuktitut covers so many things that English can’t.

English is a very basic language; when we talk about things like healing or love or positivity, we just say it like that. Whereas in Inuktitut, it’s not just a feeling you say — it’s something that’s embedded in who you are. So when I hear Inuktitut, and when I hear stories being told in Inuktitut, to me that’s not just a different language; it’s a different way of expressing and showing emotion.

AM: It sounds like working in Ottawa will be a big change for you.

MQ: I’ve lived in the South before, and I have family in the South who I visit, but it will definitely be an adjustment again. I’ll be spending about half my time in Ottawa when the House is in session. Then, on our off months, I’ll mostly be in the territory.

“There are a lot of things that need to change, and I think your day-to-day Canadians are ready for it.”

AM: What worries you about Nunavut’s future?

MQ: I’m worried that I’m still going to be having the same conversations in four years as I am today. That things won’t shift even though I’m in the House of Commons now.

We need a lot of things to happen and a lot of people to be more understanding at the federal level for us to see certain things change.

I don’t want my nieces and nephews to have to be talking about the same things that I was talking about growing up. I don’t want future generations to talk about friends and family that they’ve lost to suicide. I don’t want them to have to be worried about starting a family or getting a job or pursuing post-secondary studies or taking care of a family member.

In order for those kinds of things to happen, there are a lot of services that need to be created or drastically increased.

AM: What resources would you recommend for learning more about Nunavut?

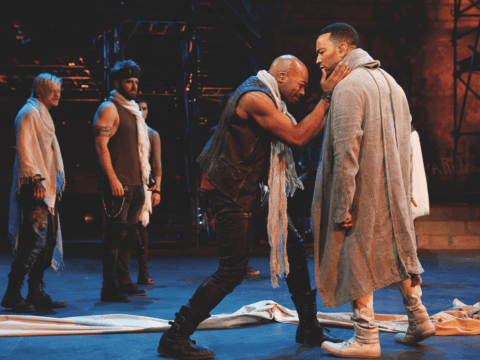

MQ: We have amazing musicians, performers and artists. There’s also the Qikiqtani Truth Commission, which talks about the history of the communities in the Qikiqtaaluk Region. You could look up Stacey MacDonald, Celina Kalluk, Ippiksaut Friesen, Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory, Tagak Curley, Paul Okalik, Paul Quassa, Natan Obed and Kilikvak Kabloona. And, I’d say watch Angry Inuk. I know [filmmaker] Alethea Arnaquq-Baril personally, and she’s amazing.

AM: Is Canada ready for reconciliation?

MQ: I think Canada as a whole is. But I don’t think it’s coming from the individuals it needs to come from. There are a lot of things that need to change, and I think your day-to-day Canadians are ready for it. I’m not sure if the individuals with power and the ability to make change are ready, or what they’re doing about it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity. It first appeared in Broadview’s April 2020 issue with the title “Mumilaaq Qaqqaq.” The print version of this article states that Qaqqaq is 27 years old; she is actually 26. This version has been corrected.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.