I’ve always found Mary Magdalene to be a bit of a cipher, a two-dimensional figure in a story filled with complex characters. I can empathize with the all-too-human disciples when they ask silly questions or boorishly fall asleep in the garden. For a long time, though, Mary left me cold. That may have been because she isn’t given any family history or much context. The only bit of backstory we’re told is that she was once possessed by seven demons. It makes for a memorable entrance, but the fact that it’s never explained or even referred to again somewhat dampens the effect.

Her final appearance is just as dramatic: she’s the one who discovers the empty tomb and, at least according to John, she has an intimate encounter with the risen Christ. These two scenes that bookend Mary Magdalene’s presence in the biblical narrative hint at an important and fascinating woman, but beyond them there’s not much to go on — she’s only mentioned about a dozen times by name throughout the four canonical gospels, often as part of a laundry list of Jesus’ female followers.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In spite of this, Mary holds an outsized place in Christian popular culture, perhaps because the large gaps between the sensational details leave plenty of room for speculation. Her legend has grown enormously over the past two millennia, mostly at the hands of men. She’s presented by turns as a fallen woman, a penitent, Christ’s lover or some heady combination of all three. In art, she’s frequently nude, sometimes lounging in a cave, repenting at the viewer’s leisure. Trying to unravel her myth means digging through layers and layers of male gaze, but I think doing so is both possible and necessary.

More on Broadview: Forget meek and mild, the Virgin Mary was a slam poet

A good place to begin tugging at loose strings is on an Easter weekend in Rome back in the sixth century AD. At Good Friday mass in 591, Pope Gregory I, also known as St. Gregory the Great, launched a campaign to redefine the legacy of Mary Magdalene. Mary, he said, was the unnamed sinner woman with the alabaster jar who appears at Simon the Pharisee’s house to anoint Jesus’ feet. In another homily delivered soon after, Gregory embroidered on this theme: not only was Mary the sinner woman, but her greatest sin was lust. “It is clear,” he added, “that the woman previously used the unguent to perfume her flesh in forbidden acts.”

No scripture supported any of Pope Gregory’s assumptions, but that didn’t matter. In these two sermons, he laid the foundation for a version of Mary Magdalene that would overshadow everything else. Gregory was not the first man to try to diminish or alter the story of Mary’s relationship with Jesus, but his words would finally seal her fate for the next millennium and a half. With them, a new tone was set, one that would see the role of women in Easter increasingly sidelined over the years.

Before we can understand how and why Mary Magdalene’s story has been reshaped, first we have to look at what we do know about her based on scripture. She’s one of a number of women with the same name: out of the 16 named women in the gospels, six of them are called Mary. There’s Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, Mary the mother of James, Mary of Clopas and “the other Mary” from Matthew 28:1. To add to the confusion, some of these women might actually be the same person, just referred to differently by various gospel writers. Then again, maybe they’re all unique individuals. According to historians, enough women in Judea at the time were named some variation of Mary, Maria or Miriam to put even the Jennifer trend of the 1970s and ’80s to shame. The reasons for this popularity were almost certainly political — Judea was occupied by the Romans, and the name Miriam had links both to Jewish history as well as to the dynasty that had ruled an independent Judea before Rome.

I find the wording of Mary Magdalene’s name to be interesting in and of itself. In the original Greek, she’s never actually called Mary Magdalene, but “Mary the Magdalene,” “the Magdalene Mary” or “Mary called Magdalene.” Some scholars speculate that she may have been from a town called Magdala, which makes sense since there is one on the coast of Galilee. Others, however, have suggested that “Magdal,” which translates as “tower” in Aramaic, is an epithet given to her by Jesus. He was fond of nicknaming his followers, referring to his apostle Simon as Cephas (rock) and his apostles James and John as Boanerges (sons of thunder). Given this, it’s possible that she wasn’t Mary from Magdala at all but Mary the Watchtower.

So if Mary was “The Watchtower” to Jesus — someone who, like him, was watching out for the safety of the flock — maybe one of the reasons for that name was because she was funding his mission. We know that Mary was a Jewish woman from the Galilee area, and based on the relative freedom she seems to have had, she was likely wealthy and of high social status. In the Gospel of Luke, we’re told that as Jesus makes his way through the countryside preaching to crowds, he’s accompanied by his 12 disciples, “as well as some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, Joanna, the wife of Herod’s household manager Chuza, Susanna, and many others. These women were ministering to them out of their own means.”

Her legend has grown enormously over the past two millennia, mostly at the hands of men.

In his depiction of her, Pope Gregory I interpreted Mary Magdalene’s seven demons as representing the seven deadly sins. This was around the same time he codified what would become the standardized list of cardinal sins, so perhaps he thought this would be a good chance to offer his audience a concrete example. Whatever his reasoning, there’s nothing in the text to support his theory. Demonic possession within the context of the gospels is commonly mentioned alongside physical and mental illnesses, never as a suggestion that someone has lived a sinful life. I agree with the theologians who have said that it’s much more likely Mary suffered from seizures or some kind of psychiatric illness. If the number is significant, it’s probably because seven symbolizes completeness in Jewish tradition, meaning that Mary had been entirely overwhelmed by her condition before being healed.

The next time Mary Magdalene appears in the Bible is at the crucifixion, when Luke tells us “all those who knew Jesus, including the women who had followed Him from Galilee, stood at a distance watching these things.” This is the point when women, who I can only assume have been with Jesus all along, begin to take prominence in the narrative. They are the ones who stay and witness Jesus’ death after the disciples have fled. They are the ones who follow Joseph of Arimathea to the burial site. And, of course, they are the ones who first learn of Jesus’ resurrection.

The gospels vary in their accounts of who first visited Jesus’ empty tomb. In Luke, it is just “the women”; in Matthew, it is “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary”; in Mark, it is “Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome”; and in John, it is just “Mary Magdalene.” The common denominator in all these accounts is Mary Magdalene, and even when multiple women are mentioned, her name always comes first.

In John’s version, she meets the risen Jesus face to face. Their closeness seems evident to me from her panic at discovering that Jesus is gone; she kneels by the empty tomb and weeps, thinking that someone has moved or stolen the body. When she realizes that Jesus has risen, she cries out the Aramaic word for teacher and tries to embrace him. Between that moment and the one when she relates to the disciples what has happened, she alone is the entirety of the Christian gospel on Earth. She becomes the apostle to the apostles, the first one to preach the Good News of the resurrection.

After this pivotal scene, Mary disappears from the Bible. She is not mentioned in any of the books that follow the gospels, although she might be one of the unnamed women present at Pentecost. It’s obvious that she was a devoted follower and believer, so I find it strange that she would choose this moment to fade into the background and let the others follow Jesus’ command to spread his story. The fact that she’s never mentioned again feels more like a deliberate omission on the part of the men writing the New Testament than an accurate reflection of what happened. This feeling is only strengthened when we look at Mary Magdalene’s role in the non-canonical gospels.

Sometimes referred to as the gnostic gospels, these early Christian religious texts were rejected for one reason or another when the New Testament was being assembled in the late fourth century. In the centuries between Jesus’ death and the creation of the New Testament, Christian communities had sprung up in different parts of the world, and many had their own texts. It’s important for us to remember that these gospels were not considered unorthodox by the communities that used them. They may seem heretical to some Christians now, but that’s only because the idea of the New Testament as the one true account of Jesus’ life has become so deeply ingrained.

We also have to remember that the councils that chose which gospels to include were made up of powerful men who had a particular narrative that they wanted to promote. This is what early Christianity scholar Karen King of Harvard University refers to as the “master story,” which she says “asserts that an unbroken chain stretching from Jesus to the apostles and on to their successors — elders, ministers, priests and bishops — guaranteed the unity and uniformity of Christian belief and practice.” The non-canonical gospels, many of which had existed for as long as some of the canonical gospels, had to be declared heresy in order for the orthodoxy of the canonical gospels to be established.

It’s in several of these texts that we learn a lot more about Mary Magdalene. She features heavily in the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Philip. In each, she’s described as being both the follower closest to Jesus as well as the most understanding of his message. In the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, which is not purported to have been written by her, she appears to be the leader of the disciples after Jesus’ death. At one point, Peter says to her, “Sister, we know that the Saviour greatly loved you above all other women, so tell us what you remember of his words that we ourselves do not know or perhaps have never heard.”

The Gospel of Philip describes Mary as Jesus’ “companion,” and has a damaged passage that is usually translated as “Christ loved her more than all the disciples, and used to kiss her often on her mouth.” When the disciples ask Jesus about this favouritism, he replies, “Why do I not love you like her? When a blind man and one who sees are both together in darkness, they are no different from one another. When the light comes, then he who sees will see the light, and he who is blind will remain in darkness.”

Reading these passages was like having a blurry image come into focus; all the shapes that I’d been struggling to make out were suddenly thrown into sharp relief, and they weren’t at all what I’d imagined. Mary made sense to me for the first time. I could finally understand the scene at the tomb, her profound grief at the missing body, her attempt to embrace the risen Christ.

Pope Gregory I had tried to recast Mary’s relationship with Jesus as being somehow scurrilous — at least on her end — and his followers had readily believed him. In a patriarchal monotheistic religion, having a woman as Christ’s closest follower doesn’t fit with the “master story,” which positions only men as Jesus’ successors. It’s no wonder the early church might have felt threatened by gospels that showed any woman other than the pure Virgin Mary in a divine feminine role. Mary Magdalene was an inconvenience that had to be erased.

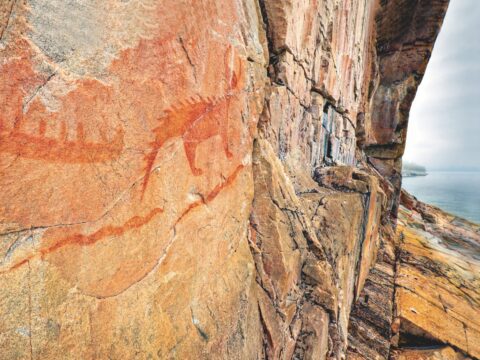

This was also true for all the women present at the crucifixion. Another possible reason for diminishing their roles might have been the early church’s efforts to distance itself from nearby pagan religions, even as it co-opted some of their traditions. In the region surrounding Judea, several faiths had resurrection narratives that predated those in the Bible. In Egypt, the god Osiris was brought back from the dead by his wife, Isis, so they could conceive an heir. In Anatolia, mother-goddess Cybele’s consort Attis mutilated himself, died and came back to life. In Greece, Demeter’s daughter Persephone was forced to spend a portion of each year in the underworld but was reborn each spring. Further back in time, the Sumerian goddess Inanna was dead for three days before being revived. What links all of these stories is both the central role women play and the agency, often sexual, that they have.

Mary Magdalene was an inconvenience that had to be erased.

As Christianity spread, it began to borrow iconography from some of these older faiths. One example is the similarity between images of the Virgin Mary with the infant Christ, and images of Isis with her infant son, Horus. This was smart marketing, an easy way to help the new religion appeal to possible converts. But church leaders began to see some of the blurred lines between Christianity and other faiths as dangerous to their orthodoxy.

It seems likely to me that the men who were invested in the “master story” of male succession in the church and society were frightened by the similarities Mary Magdalene had to these sexually expressive pagan goddesses. So it became important for men like Pope Gregory I to alter Mary Magdalene’s story into that of this lustful yet repentant woman, with any hint of sexuality either condemned or erased. Given what we know of Jesus, it’s hard to imagine that he’d be impressed.

Women in first-century Judea lived with strict gender roles and were limited in the ways they could participate in religious rites. The fact that Jesus included women in his mission at all was unusual given the time and place. His close interactions with women outside of his family, such as allowing them to anoint him and wash his feet, were a departure from the cultural norms. The women themselves must also have been radicals, travelling independently with Jesus and bankrolling the whole expedition. It’s clear to me that they had very different views of what a woman’s role in both society and religion could be.

Instead of highlighting these possibilities, the church leaders chose gospels in which Mary and other women are silenced, sidelined and diminished by their male counterparts just days after Jesus’ resurrection. In Luke, the disciples react with disbelief and scorn when the women tell them that Christ has risen. The same thing happens in the extended version of Mark.

This erasure continues to this day. Even though Mary Magdalene plays a significant part in the resurrection narrative, she is often ignored or downplayed in modern celebrations of Easter. Every Easter service I’ve ever attended gives more focus to the disciples, from their attendance at the Last Supper to their dawning realization that Christ really has returned. Even King Herod and the two thieves crucified alongside Jesus tend to get more attention. Mary’s experience of the resurrection is treated as a footnote, even though Christianity might not even exist without her.

The things Jesus did and preached were revolutionary, including his treatment of women. He foresaw everything about his death and resurrection, even Peter’s denial and Judas’ betrayal; if Mary Magdalene was the one who discovered the empty tomb and carried the message of Christianity to the rest of the world, I think it was because Jesus chose her to do so.

Thanks to the spin Pope Gregory put on Mary Magdalene’s story, we tend to view her relationship with Jesus as some kind of parable to prove how tolerant and forgiving Jesus was. Can we change this script and accept that instead of loving Mary in spite of who she was, he loved her because of who she was? Can we accept the possibility that, as the non-canonical gospels suggest, Mary Magdalene was the follower who most profoundly understood Jesus’ message? Or is that idea still too radical for Christians even 2,000 years later?

If Mary has been a mirror that reflects men’s anxieties about women and sexuality and power, she can also be a mirror for women who are looking to see themselves in Christianity. Scholars like Karen King have tried to create an environment where that’s possible by dismantling the mythology surrounding her, but it’s an uphill battle. The image of Mary as a half-clad penitent persists even in modern adaptations of Jesus’ story, offering her body up for titillation or admonition and rarely granting her the autonomy she deserves.

I find myself imagining a different narrative, one where Mary was the watchtower to Jesus’ shepherd. It’s not easy to counter a lifetime of teachings, but I’m trying to hold on to that lens through which I was able to see her in focus, a powerful and important figure in Christ’s life. I don’t feel like this ruins any of my beliefs, but rather joyfully complicates them. Faith is a living thing, something that should be allowed to change as our understanding shifts. Jesus knew that; we can know it, too.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s April 2020 issue.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Your narrative proves people just don’t read their Bibles, they take what has been told them as “gospel”. If we read it we would understand Mary’s role in the gospel.

I’m also offended by today’s thinking that Jesus married Mary Magdalene (da vinci code).

Sadly, your narrative seemed like “male bashing” and took away from the positive position the women had in the Gospel narratives. Some cut and paste from Wikipedia didn’t help either.

This is an inaccurate, unhelpful, regurgitated comment that says much more about you than the piece itself. Add yourself to the long line of weak men offended by strong women throughout the ages and feel ashamed.

I’ll assume you were writing to me. Perhaps the author could do a topical discussion on the disciple James (the lesser) He was mentioned in 3 gospels, and Acts (only in lists). How deprived, especially with his position.

Women in the days of Christ sponsored religious leaders, as the religious leaders devoted their time in learning and leading, it was cultural, not demanded, or demeaning. Mary Magdalene had the distinction of being mentioned in all four gospels, and the right to proclaim a risen Christ (women in those days were considered unreliable witnesses). Aside from the birth of Christ, Mary Magdalene is mentioned more times the Mary the mother of Christ.

Aside from that I hope you feel better – for a weak man I have broad shoulders.

A well thought out piece which challenges the reader to examine their view of Christian male-female equality. The veil of ancient paternal power and control is lifted for a peek at how Jesus viewed woman.

I am simultaneously moved, and relieved, by Anne Theriault’s article on Mary Magdalene. This is deep, making surface in my soul, and defies adequate summation.

As the author states, “Faith is a living thing, something that should be allowed to change as our understanding shifts. Jesus knew that; we can know it, too.”.

There seems to be a growing suppression of women in the New Testament. Paul in Corinthians says that a woman should not pray or prophesy with her head uncovered (or hair unbound) which may have been simply enforcing decency according to the standards of the day, but she was still praying, presumably aloud, and prophesying. The Pastoral Epistles demand that women be silent.

However, I suspect the Gnostic Gospels as they were probably written in the second century, whereas the canonical gospels were written in the first, and they seem to deny the divinity of Christ. Valentinian Gnosticism as portrayed by Irenaeus (who praised the woman martyr, Blandina, and does not appear to me to be misogynist) posited a series of aeons and denied the Incarnation. They also devalued the material creation, which Genesis said was good.

A few years ago listening to the account of Mary and the “gardener” I had a bit of an epiphany: Mary Magdalene was OLD!

Excellent. Well written and researched. I presume the women following with Jesus could be considered disciples given my understanding of the word and not just mindless and ignored servants. Also from some of the comments, I can’t forget that a council of men representing many sects of Jesus followers were forced to decide the substance of Jesus: man, God, or both. Meaning different sects had opposing views.

Wow, “… I think it was because Jesus chose her to do so” really got me. After more than a decade of religion classes growing up, I realized there was probably a good bit missing or mistranslated from the Bible. The class even asked once if it was possible the Gospel collators chose what to exclude to suit their needs, and the response was “no, the Holy Spirit guided them.” Might have even been about the Gospel of MaryM come to think about it.

I am not a Christian, I am a Jew. We Jews spend much of our study time discussing, arguing, considering what a word means, who translated it from what language, if perhaps that translation could have been in error, etc, etc, etc. We consider this as bringing us closer to our faith. Blind acceptance of words written by men is always risky: only G-d is without error.

This article, to me, embraces the style of deep scholarship that Jesus, as a Rabbi himself, would have engaged in. It was a pleasure to read and gave me a great many things to think about, as well as adding to my reading list.

Thank you for bringing this topic to light again. I appreciate your scholarly references and your perspective. I too have been a follower of Mary Magdalene and wondered about the reality of her relationship with Jesus. You have proved that she does indeed deserve more thoughtful discussion and raised status in the church. We are lucky that there are very open and radical Christian sects that permit this discussion without being offended. Women indeed are powerful and influential followers of Jesus and can bring a fresh new perspective to Christianity in the 21st century. Well done!

I have always thought that it was logical for Jesus to choose Mary Magdalene to be the first to proclaim His resurrection.. Having been healed of terrible mental and physical suffering (perhaps epilepsy) she already felt a resurrection of sorts in her soul, mind and body.. Who better could have proclaimed the power of Jesus’s resurrection with conviction.