Rabbi and theologian Julia Watts Belser brings disability justice perspectives to ancient Jewish texts, uncovering fresh insights that challenge traditional religious understandings. A professor of Jewish studies and disability studies at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., Belser also connects queer, feminist and environmental ethics with Judaism.

In her 2023 book, Loving Our Own Bones: Disability Wisdom and the Spiritual Subversiveness of Knowing Ourselves Whole, she invites us to reimagine disability not as something to be overcome, but as a source of sacred wisdom.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Belser’s theological innovations recently earned her the prestigious 2025 Grawemeyer Award in Religion. She spoke to Amy Panton, assistant professor of practical theology at Emmanuel College in Toronto and editor at Mad and Crip Theology Press.

AP: Your book begins with the striking image of God on wheels. What led you to reimagine divine presence in this way?

JWB: This moment is really grounded in a particular experience of revelation. As a wheelchair user, I was sitting in synagogue during Shabbat when Jewish communities worldwide chant from the Book of Ezekiel. The Hebrew prophet has this startling vision of God’s divine chariot, and he keeps coming back to these huge, glorious, gleaming wheels. It landed so powerfully in my own body — this sense of knowing, this sense of kinship, this recognition that God has wheels too.

God on wheels has been a powerful way to claim the theological significance of disability joy — the beauty that wheels can bring into this world. But wheeling through this world isn’t always a pleasure. It’s also become a potent image for thinking about inaccessibility, how so many of us get shut out of so many aspects of life. God, too, faces barriers to access and knows the pain and frustration of being shut out.

AP: You write about disability not just as a medical condition but as a source of wisdom. How does this challenge religious understandings of disability?

JWB: I take a political view of disability. When we talk about disability, we need to think about social and political barriers. Disability is intimately intertwined with ableism — systems, practices and policies that stigmatize disability and deny disabled people access, agency, resources and self-determination.

Whenever I talk with religious communities, I always want to emphasize that disability is a justice issue. We want to think about disability in relation to power, inequality and injustice. When we approach disability that way, I think it becomes a lot easier to see how disability gets bound up with normativity. It’s not just about stigma; it’s about how we’ve built the world. We live in a society that’s set up to enable certain kinds of bodies and minds while disabling others.

AP: Many faith communities approach disability primarily through healing or charity. What shifts when we centre disabled people’s own spiritual experiences?

JWB: In disability spaces, people are often deeply hesitant to engage with religion, for good reason. Religion has been weaponized against disabled people through narratives of faith healing and those frustrating cultural tropes — “disability is our greatest teacher” or “God doesn’t give us more than we can bear.” Religious communities have often treated disabled people as symbols of suffering or exemplars of tragedy. But I’m not a symbol. I’m a self. We need religious narratives that honour the full, gritty complexity of our actual lives.

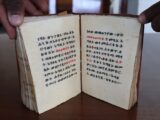

AP: Your reinterpretation of biblical figures like Moses offers new perspectives on disability. Could you share an example?

JWB: Moses is an extraordinarily significant prophet in Jewish and Christian tradition, and I recognize him as a disabled prophet. When God first calls to Moses and sends him to speak to the Pharaoh, Moses says no — God, you’ve got the wrong guy. He describes himself as having a “heavy tongue,” which scholars often associate with a speech disability. God’s response is powerful: “Moses, who made your mouth?” It’s a recognition that disability is part of God’s own design, not an aberration.

But Moses is completely unmoved by this response. He says, “Don’t send me to Pharaoh. Don’t make me go talk to that cruel, harsh man.” It’s such a powerful reading of ableism in action — Moses understands that his disability will be used against him. In response, we see what we might call the first reasonable accommodation in the Torah: God responds by redesigning the plan, saying, “Take Aaron your brother; let him be your voice.”

When God sends Moses to speak to his own community, Moses has misgivings: “What if they don’t listen to my voice?” God responds by granting Moses the gift of signs — visual, gestural language. It’s a radical reorientation, saying, “Express revelation in the language most kin to your own heart.” This moment cracks open our expectations of what divine communication might look like, inviting us to reimagine how revelation itself might manifest in the world.

More on Broadview:

AP: A radical reimagining of divine power through the lens of interdependence is a focus of your work. Could you elaborate on this vision?

JWB: So often, conventional theologies imagine God as all-powerful — it’s like all ability, all the time. But I think it’s theologically interesting to consider God as experiencing disability, as knowing something about disability experience from the inside. When I think about God, I’m drawing on contemporary Jewish thought that sees God as someone who needs us, who is in fact dependent on human beings to partner with and show up for God. As far as I can tell, God can’t pick up a single stone without a human hand to do it.

I think about how much of my own life as a disabled person is built around recognizing limits, not always being able to do everything for myself. While there’s incredible vulnerability in that, it can also open up a profound invitation for intimacy. So many disabled folks rely on other people to help us navigate daily living, and we get really skilled at organizing and directing other people. I love thinking about that as a skill that God also has — God is also in the business of marshalling a staff, orchestrating sometimes unreliable humans to do God’s work in the world.

AP: You write about the importance of rest and Shabbat — taking 25 hours each week to deliberately unwind from work — through a disability justice lens. How might this perspective inform how faith communities think about productivity and worth?

JWB: We live in a world that emphasizes more, more, more — faster, faster, faster. This is one of the most pernicious ways that ableism affects all of us. While it’s crucial to recognize how ableism is weaponized against disabled people specifically, increasingly I see that ableism isn’t good for anybody.

We’re continually living in a world that demands and expects us to be productive at all times, judging our worth on the basis of our work. It’s such a lie.

As someone who often lives a very high-pitched, fast-paced work life, this spiritual practice of unbinding from the expectation to do and make and perform has been one of the most profound calls to reclaim a sense that my worth is grounded in who I am, not in what I can do.

This is a truth I’ve learned most acutely from working in the disability community, especially from folks with chronic illness, chronic pain and energy-limiting disabilities. They have helped school me in a different way of being, in recognizing my own bodily limits and acknowledging that tending to the sustainability of my body-mind matters — that it can, in fact, be spiritual work.

AP: How might disability wisdom help us reimagine our relationships with our bodies and the divine?

JWB: Disability wisdom invites us to reckon more gently with our limits and needs. When I have an ache in my knee or hip, I’ve learned to lay my own hands upon these places and offer love and care to my own bones. Choose your own adventure, but for myself, I often think about inviting divine attention, God’s presence, into those places of love and ache — to hold them with tenderness, to recognize that they are a site of both possibility and vulnerability.

One of the things that’s been so incredibly beautiful to me is to watch the extraordinary artistry of disabled artists and activists, the way so many of us are working to hack an inaccessible world that wasn’t built for us. In doing so, we create ways of being that are creative, capacious, joyful, gritty and filled with the possibility of reimagining life itself.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Amy Panton is assistant professor of practical theology at Emmanuel College in Toronto and editor at Mad and Crip Theology Press.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s June 2025 issue with the title “Reimagining God on Wheels.”