Dear Sacha,

On my desk, if you could see it, there is a disorganized pile of papers, things half-started or half-finished, things to read or write or do that I have set aside to do later. Seized with New Year’s resolve on this late December day, I have taken your letter, dated June 13, 2020, out of that pile and am ready, finally, to answer you, maybe even with a handmade card, something colourful for you to look at in your jail cell.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“Hello James,” you began, “I dont know if you remember me, my name is Sacha Bond. I had wrote you back awile ago, my mother had given me your address after you had mentioned my name in a article you had wrote caled James Loney: Canada Came to Rescue Me. Why Not Arar, Khadr, Mohamud?”

Yes, Sacha, I do remember you. We have an unfortunate thing in common. I was once, as you still are, a Canadian in trouble abroad. In November 2005, I was kidnapped by Iraqi insurgents while leading a Christian Peacemaker Teams delegation in Baghdad. Three other men were with me: another Canadian, a Brit and Tom Fox, an American who was killed two weeks before our release.

More on Broadview:

- Canadian Jesuits call for the release of 83-year-old human rights defender

- Detained abroad? Turns out, Canada isn’t legally required to help you

- During COVID-19, former prisoners are re-entering a world with fewer supports

The envelope your letter came in had a red stamp on it that said “MAILED FROM STATE CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTION.” In the upper-left corner, you had written your name, prison number and return address, “Apalachee Correctional Institution East/unit.”

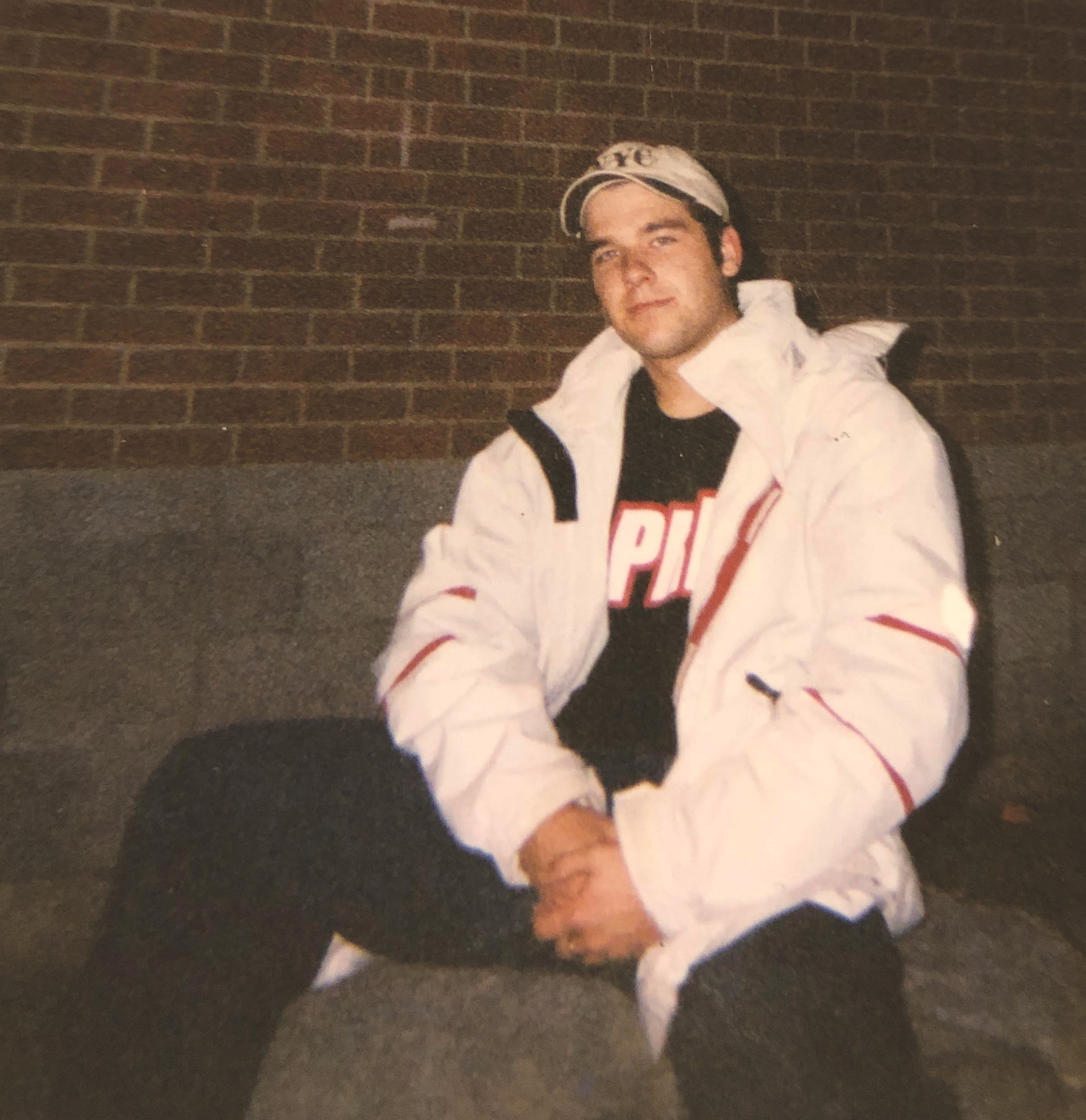

Your life changed forever after a Saturday night outing went horribly wrong. You were 19, off your meds, on a family vacation in Florida visiting the man who was your stepfather at the time. You took his car to a strip club on Jan. 31, 2004, and they let you in even though you were underage.

What happened next is a blur. The official version says you drank too much and got kicked out after getting into an argument. You found a gun in your stepfather’s car, went back, pointed it at four different people and pulled the trigger. The chamber was empty.

You, however, remember leaving peacefully after being forced to pay for a lap dance you had already paid for. Then you blacked out. Conflicting accounts surfaced, and key witnesses did not come forward. In the end, it came down to the word of the bar staff.

You were convicted on four counts of attempted murder and sentenced to 20 years without parole — the same crime would have gotten you 10 years in Canada. Apparently the jury asked three times for the meaning of “bipolar disorder,” something you had been diagnosed with just six months before.

I immediately felt guilty when your letter arrived. I’m sure you can guess why. It has been seven years since we last exchanged letters, since I was last in touch with your mother, Diane Levesque, your roaring lion and inexhaustible champion, who has been reaching for you across a border, over a barbed-wire wall, through metal bars, seeking out anyone who will listen — her member of Parliament, the prime minister’s wife, the Canadian Consulate, the media, friends and family, me — trying to find a way, any way, to get you home to Canada.

“Canada did nothing to come get me. Boy even today I still got my hopes that they would come for me.”

Letter from Sacha Bond

You reached out to me; I reached out to your mom. We corresponded, talked on the phone. I went to visit her at her home. I promised to help and started to, but something inside me, whatever the thing is that generates life purpose, sputtered and then collapsed.

You see, I had just finished writing a book about my kidnapping experience. It took me three years from the first word to the last edit. I could see it coming, the publication date, April 2011, as if I were rowing a boat toward shore. When the day finally came for me to get out of the boat, I found myself on a strange shore without a map, unable to make decisions, incapable of taking initiative.

I did whatever people asked me to do — a talk, an interview, a workshop, a piece of writing. To the world, for a while, I was a leading peace activist, but on the inside, I was in anguish and I didn’t know why. I continued along in my activism, even with plans of building a youth social justice network anchored in a summer leadership camp, because that’s what I had always done. That’s what I felt was expected of me.

I started therapy. Months passed, and I felt endlessly stuck. Then it happened. My pilot light came back on, I don’t know how or why. I was on a bus to Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., travelling to see my mother. The driver stopped in Blind River for a 15-minute coffee break, and I went for a walk down the main street of the town. Maybe it was the June flowers or the new-budding trees or the river flowing by — how you must long for those things! Whatever it was, the eyes of my heart opened with tears, and the feeling of wanting-to-do-something spontaneously returned.

A question formed in my mind: maybe I could go back to school and learn how to share trauma healing work with others? No, I chided myself, you need to work on changing the systems that cause all the trauma —capitalism, militarism, colonialism, racism — this is the better thing to do. I hurled myself into activism, hoping this new desire would go away. That’s about when I got in touch with your mother.

But, try as I might, Sacha, I couldn’t change what my life-purpose generator wanted to do, and every activist thing I tried fell through my hands like sand. I feel a pang in my heart as I imagine saying this to you and looking in your eyes.

In January 2013, I applied to do a master’s in social work. I graduated in 2015 and am now a counsellor. I love my work and feel it is a great privilege to accompany people in their healing journeys. Yet I still feel uneasy about having exchanged the public voice the kidnapping gave me for the quiet invisibility of therapeutic work. I do hope that someday my desire for activism will return.

I never communicated this to you or your mother — I didn’t know how. There wasn’t a word for it back then, but I ghosted you. It is this feeling of guilt that has kept me from answering your letter.

“Im writing you to keep in touch with you,” you wrote, “and to keep you updated about my situation. Well first Im still here in Florida, and very much still mentally ill. Unfortunately for me Canada did nothing to come get me. Boy even today I still got my hopes that they would come for me all kick ass just as they did for you.”

You are right, Sacha! The Canadian government activated a command centre, sent a task force to Baghdad, appointed liaisons who stayed in regular touch with my family and partner at the time, and joined a multinational intelligence operation to find us. It took four months, and when they did, American and British special forces closed down the street, surrounded the house we were being held in and rushed in with sound grenades exploding. It doesn’t get any more kick-ass than that, does it?

That, of course, is why I wrote the article that you mention. As you know too well, who gets helped and who doesn’t is an arbitrary matter of Crown prerogative and has led to “inequity, unfairness and inconsistency” in the provision of consular services. That’s according to Gar Pardy, a former director general of consular services, who in a 2016 report called for a law to enshrine the right to government protection for Canadians detained abroad.

Across the years of your imprisonment, the Canadian government stonewalled, resisted, delayed, obfuscated, then acceded to your request for a transfer to Canada. When Florida denied the request, the Canadian government subsided into the silence of its bureaucracies. Meanwhile, your detention continued along its grim course.

You told me in your letter that you were in solitary confinement to escape a gang that beat you up and tried to make you pay them $500. When the warden sought to put you back in the general population, you refused; it was still not safe. You wanted to be transferred to a different institution. That didn’t happen.

“Its been a very long 17 years, of beat downs, extortion, fighting the police not to get killed.” You were nonetheless hopeful and looking forward to your release in a few years. “I keep my head up knowing that god has a biger plan for me after this.” You dreamed of getting a settlement, just like Omar Khadr received, and using the money to open a bistro that would help kids with cancer, as well as donating to other important causes.

“I dont have everything figured out still but its a project that I want to have… My faith in god is very strong that he will helpe me accheue that.” Above all else, you were looking forward to seeing your mother.

Your spirit sounded strong. I thought you were doing okay. I should have written you right away. I didn’t. Days passed into weeks, and weeks passed into months.

Sacha, no! I stopped writing for a moment to Google your name, following an impulse to see if anything has changed with your situation. What I learn shocks and horrifies me.

You were not okay. Shortly after writing to me, you refused the warden’s demand to join the general population because you didn’t feel safe. They put you in the “hot box” with another prisoner. The walls were dripping wet, there was black mould everywhere and the cell smelled of raw sewage. You said it was like being locked inside a car with the windows rolled up on a hot summer day. You wrote to the Canadian Consulate, desperate for help. They did not come.

In the last letter you ever wrote your mother, dated July 5, 2020, you told her you were sweating constantly and a heat rash covered your body. “This should be illigal….I dont know what to do, nobody is agnoleging me.”

On the morning of July 13, they found you lying on your side, unresponsive, vomit spewed out of your mouth. You were taken to a hospital with a temperature of 41 C and put on life support.

It was a prison inmate who alerted your mother to what happened to you. A consulate official confirmed you were in the hospital; they couldn’t say which one. Neither would the prison, until a sympathetic worker broke the rules and told her off the record. When she finally found you, when at last she could touch-you-kiss-you-shed-her-tears-on-you, your blood was infected, your lungs and your liver and your kidneys were failing, your brain was irreparably damaged.

It was like “watching someone getting squashed in a garbage compactor in slow motion.”

Eric Bond, Sacha’s brother, on the hospital stay

Your mother took you off life support on July 31. Then she waited with you, sleeping in a reclining chair next to your bed, as your body and spirit struggled, breath after breath, to keep on living. She cut your hair, shaved your face, put drops under your tongue when you coughed and played your favourite music — while two armed guards kept watch day and night. Your legs were like sticks, your feet were swollen, your ankles bandaged to cover up the oozing wounds caused by the shackles that still bound you. The guards would not remove them. “He’s still ours,” one of them told your mother. “He still belongs to us.”

You took your last breath on August 16, 2020, at 8:07 p.m. Your mother was not allowed to be with you. She had to leave at 7 p.m., the regular conclusion of visiting hours. The guards did not remove the shackles from your body for another three hours. Your brother, Eric, told the Canadian Press it was like “watching someone getting squashed in a garbage compactor in slow motion.”

Dear Sacha, words fail me, but let me try. You were condemned to a living hell and eternal state punishment for an impetuous act in your youth. You were left to rot in a steel tomb and died chained to a bed in a coma, a human being desecrated and forsaken, your family watching helplessly as your life was snuffed out, like someone crushing a used-up cigarette with their foot. The cruelty of it is impossible to take in.

A new year is coming, and these words, for what they are worth, are too late. You will not read them; they will be of no consequence to you. The things I have not done cannot ever be undone.

Sacha, it is a fact, and I must say it. I, who did not find the time to answer your letter, am as much a part of the chain that bound you as the Florida voters and taxpayers and politicians who enacted the laws and paid for the prison system and hired the warden that commanded the guards who watched over you. As much as the voters of Canada who elected the governments that determined the responses of the consular staff who did not, or could not, do enough. As much as the voters and taxpayers of Quebec who elected the governments that have failed, year after year, to create an accessible mental healthcare system that could have helped you. As much as the bouncer who let you into the bar that night; your stepfather who left the gun in his car; all the people who insist upon the unlimited right to buy and keep guns; a culture that compels young men to assert their masculinity with their fists or a weapon — these, and a thousand million other complicities and omissions, accumulated and exponentiated and diffused a thousand million times to knit an invisible chain far stronger than the one that bound your ankles.

The thing about an undone thing is that you never see it. Because it never happens, it can seem not to exist, or even not to have consequences. But my undone thing does exist. It lived in your suffering and now perpetually in your death. And this is why, maybe, words do matter, and why they must be spoken, even if it seems to be too late. They can make visible what is invisible. You were trying, by your letters and phone calls — by your words — to make yourself visible. Being seen and heard is life itself.

Sacha, your last words to me were words of friendship. “Well anyway’s,” you wrote, “I hope that this letter finds you in good health and are keeping your head up also” There was no period. And then you signed, “your friend Sacha Bond” Also without a period. I liked that. Good wishes and friendship are open-ended possibilities and should never be punctuated with periods.

Yes, a new year is coming, dear Sacha, and though it is now too late for you, it is not too late for me. To see again, to act again. I have never been able to keep a New Year’s resolution, so I dare not make one now for fear that, in my characteristic way, I may not follow through. But this I can promise: I will hold your memory close to my heart as a living reminder of what I allow when I fail to act.

I am truly sorry. This should not have happened to you.

Your friend in spirit,

James

***

James Loney is the author of Captivity: 118 Days in Iraq and the Struggle for a World Without War. He works at Anishnawbe Health Toronto as a counsellor.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Quotes from Bond’s letters remain faithful to his original spelling, as per his family’s wishes. Irregularities in capitalization and punctuation have been edited for readability.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s June 2021 issue with the title “Letter to a Fellow Prisoner: Former Hostage James Loney Writes to a Canadian Inmate in Florida.”

Excellent editorial. The boilerplate “keep the peace and be of good behavior” is probably the most significant bail condition. That hasn’t changed as a result of the decision.