Social etiquette says that talk about money, religion and politics in public doesn’t mix, but discussing the last two were how my partner and I introduced ourselves to each other on our first date. It was the only way we would know there would be a second.

I am a Black woman who grew up in the church and attended a Christian elementary, high school, and summer camp. He is a white man whose Catholic father stopped attending church when stories of abuse broke from an orphanage run by Catholic educationalists. God was everywhere I looked, but my partner believed God could have shown up more.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

When my partner asked me about religion after noticing the Christian songs and Bible verses I posted on Instagram, I told him I loved Jesus, but my qualms were with the institution. I preferred to be called spiritual. He agreed with the dangers of religious systems, but his issue was with a God who would allow such pain to exist. He preferred to be called agnostic.

“God was everywhere I looked, but my partner believed God could have shown up more.”

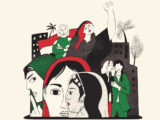

As a Black woman, marginalization is a consistent hum of snide looks, backhanded compliments, and slurs to the backdrop of my political existence. It’s a different terrain than the arthritic ache of racism my partner felt while reading about hate crimes. While he had to reflect on his past for episodes of complacency, I was reminded of being the brunt of racist jokes as early as elementary school.

Suffice it to say, I was surprised when the internet seemingly exploded with anti-Black racism awareness, from protest safety tips and etiquette to avoiding optical allyship and calls to action in various industries last summer. In the midst of this chaos, silence was deadly. Many of my Black friends expressed distrust of non-Black people’s lack of anti-racism discussions online and in reality — especially if they were white. I agreed. How can you claim to love someone, yet turn your back on them as the world contributes to their deaths? Even more troubling was how some churches did not acknowledge this, centered whiteness in their statements, or refused to listen to their black congregants’ concerns.

More On Broadview:

- Why I find it hard to accept a Black Jesus

- Why are American men are more likely to identify as non-religious than women?

- Is George Floyd’s death the start of my daughter’s ‘Black list’?

At the height of these tensions and my inner monologues, I met a man who protested for Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, condemned the homophobia, pedophilia, and colonial history of the church, and was altogether a great man… who just happened to be at odds with two identities that shaped how I see the world.

To be honest, I was worried. Would I find dormant racism? Would he reject my love for God while I grappled with the abuse of His followers? Instead, he asked questions that helped me deconstruct the harm and inconsistencies of a religion; ones that elevated the message of love from its deity. I found the compassion and social justice advocacy I struggled to find in Christians who preached they loved everybody, while their actions and inaction said otherwise. I found a man who apologized for what his unconscious bias missed, and assured me of what his actions would no longer allow. I found a man who cradled me when I shared just how painful a colour-blind world could be.

Our empathy assured us that our differences would not bring harm to those we loved most. He told me he was ready to explore the God I spoke about because the Christianity I practiced didn’t damn our queer friends or deny women’s right to choose. Instead of just saying I wasn’t part of the problem to differentiate myself from other Christians, I began actively condemning and separating myself from the oppressive forces of a community I grew up in.

Within these decisions to choose justice for the people around us, we found love with each other. We did not choose the families we grew up in or the skin we inhabited. We made choices about the kind of people we wanted to be — and those choices have made all the difference.

***

Sherlyn Assam (she/her) is a freelance journalist, blogger, and philanthropy and nonprofit leadership master’s student living in Ottawa.

As Christians, for the most part, we have no say in whether or not we get baptized or confirmed. It’s only as we grow do we realize the pain and suffering that organized religion has caused in the world. However, when we focus on the teaching of Jesus we can learn to live the way he taught and when we do that, we can focus on God, and how God acts and moves in our life. Love brings us beyond the mechanics…the dos and don’t of religion. Love gives us the power to move beyond the writings and the ceremony. What matters in a relationship is God’s love which drives communication, sharing, love, acceptance, laughter, self-giving and much more. We can’t choose which tent our parents place us in but as we get older we can make choices of who we will be. Love can flourish when we focus on the essentials. When we find such a person to share our life with the result is truly deep and spiritual.

Thank you for this article. The way to choose wisely is to have the facts. Much of the debate on racism in the UCC is predicated on US experience. The facts as reported by numerous black and white commentators dont support the thesis that systematic racism is the prevalent social ill in American today. For instance contrary to the MSM focus on interracial violence, roughly 11% of all murders in the U.S. are interracial. The other 89% involve people of the same races slaying one another. Contrary to progressive media- black and white people are typically arrested, prosecuted, and sentenced at rates that accord with the frequency and severity of their criminality. And statistically police are 42 percent less likely to use lethal force against Blacks than Whites in the US. All this to say that our opinions and policies in the Church must not be shaped by leaders who see the world as primarily a contested power struggle between races. This is the trap the UCC leadership has fallen into today as a result of uncritically embracing critical race theory.