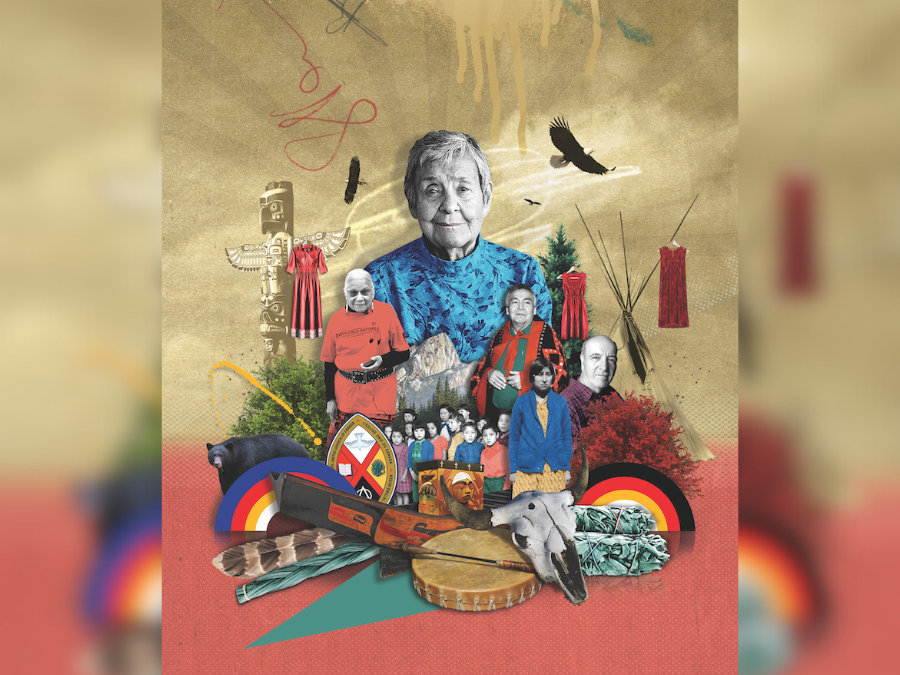

The centennial of The United Church of Canada is something to celebrate. Yet, most United Church members know little about the Indigenous Christians who share the name United. The following is a brief retelling of the journey from government wards to partners in mission. Scripture tells us to care for our neighbour as self, but how can we do such caring if we don’t know our neighbour’s joy and pain? Let me introduce you to the neighbours.

The Methodist Missionary Society began its “missions to Indians” in 1824. A century later, with the stroke of a pen, these missions became part of the new United Church of Canada. There was no consultation; most Indigenous congregations were largely unaware they had become members of a different denomination. So began the United Church’s Indigenous ministries.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The history of Indigenous ministries in the United Church is fraught with challenges and steeped in colonialism. The relationship could be described as two steps forward, one step back. The past 100 years have seen the closure of residential schools, the rise of Indigenous spiritual leadership, two apologies from the national church and an ongoing commitment to healing and reconciliation. Alongside that, Indigenous Christians have faced lingering racism, bureaucratic barriers and a resistance to true autonomy that continues to this day. If contemporary Christians are to be in right relations with Indigenous people, then this full story of our relationship must be shared.

The Canadian historical narrative of empty lands, or terra nullius, discovered and tamed by intrepid explorers, farmers and industrialists from Europe has become our national myth. This colonial origin story underlies the subsequent oppression and exploitation of Indigenous Peoples. The United Church of Canada, as a national church, absorbed this myth, carrying on the efforts of its forerunners who sought to assimilate Indigenous Peoples and convert them to Christianity.

When the Methodist Missionary Society started its work in 1824, two missionaries were sent to the colony of Upper Canada to spread the Gospel among Indigenous communities. Over 100 years later, by 1926, there were 52 Indian missions, 50 missionaries and 60 other “paid agents” — teachers, assistants, doctors, nurses and interpreters — serving Indigenous people.

In a report in the United Church’s 1926 Year Book, Rev. Arthur Barner, superintendent of the Evangelistic Missions to Indians, observed that “the Indian mind is strong in memory, but not in logic. He believes that since the white man took possession of his country, therefore, he owes the Indian everything in the way of a living.” Barner complained that the missions weren’t self-supporting in terms of pastors’ salaries. “However, the people assume a good deal of responsibility in erecting church buildings and providing for local expenses, and their missionary givings amount to about one-tenth of the entire appropriation of the Board for Indian work.”

Of the roughly 105,00 “Indians” in Canada, the United Church bore responsibility for about 18,000 in 60 evangelistic missions from Montreal to the Pacific Coast, according to the 1927 Year Book. It also operated 13 residential schools and 45 day schools with nearly 2,500 students.

In 1927, Barner opined that “the Indian himself has constituted a special economic and social problem. Possessed of certain remarkable qualities inherited from many centuries of noble ancestry he should have made a much larger contribution to the progress of Canada than has been the case. Contact with the whites has not always been to his gain, indeed it has been oftener otherwise. He has too frequently taken the path of least resistance and copied the vices rather than the virtues of his white associates. He has found it extremely difficult to give up the care-free habit of a wandering life for the more fixed and stable custom of ‘taking thought for the morrow.’” This condescending, paternalistic attitude was typical of the United Church at the time.

Barner quoted a young doctor as saying, “What a great thing it is that the Church keeps these centres of hope and encouragement for the native people. Whatever would become of them if the Church neglected them?”

What indeed? Several lessons can be learned from the early years of the Indigenous United Church. Most of these lessons are about the non-Indigenous church. The majority of United Church members were Euro-Canadian in heritage. As Deanna Zantingh observes in her 2014 paper in Direction Journal, the Christian tradition of mission regards western religion and culture as superior. “‘Christian’ came to mean ‘white’ — clean, prosperous, civilized, well-mannered, hardworking, and patriotic,” she writes. Anyone who deviated from this blueprint required reformation.

The United Church attempted to impose its standards upon Indigenous people, but it was not an easy sell. “The Indians…do not take kindly to the new civilization which is being brought to them, in the introduction of which our missionaries must do much spade work,” lamented Barner in 1930. “Very seldom can we mark much progress in any given year.”

As early as 1931, reports from the Woman’s Missionary Society expressed concern over the trajectory of home missions. Effie A. Jamieson, the WMS general secretary, quoted a mission worker who observed that “there can be no vitalizing life in an Indian community unless there is leadership.” Moreover, this leadership needed to come from Indigenous people: “Unless all the work of the Government and all the work of the Church is directly related to the transfer of the load [economic and otherwise], we shall have to continue to work for them indefinitely and the lethargy of expectancy will tend to grow.” This acknowledgment of the need for Indigenous leadership is critical. It points to the dawning understanding that mission work is bound to fail without the co-operation of the Indigenous communities themselves.

More on Broadview:

Being part of a church was a nuanced decision for Indigenous people. It is important to note Indigenous self-agency. Some joined because they had experienced a genuine conversion. Others decided to adopt colonial Christianity because they thought it would benefit their children, who were forced to live in this new world. Still others rebelled and were Christian in name only, if at all.

By the mid-1930s, it was clear that the approach to missions wasn’t working. Representatives from the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian and United churches created a joint committee to share ideas and best practices “in the interests, not simply of the children in the schools, but of the Indian people as a whole.”

Writing in 1936, Barner’s successor was pessimistic, noting “very serious problems in human conduct, including intemperance, laxity in marriage relations, and in some cases a recrudescence of heathen customs.” Intensive colonization had left Indigenous communities worse off than they had been before the imposition of Christianity.

***

The Second World War changed everything. A global reorganization of countries led to widespread decolonization among the European colonies. In Canada, the colonizers did not leave, but an immigration surge in the postwar period helped the United Church change its perspective by learning about other world religions and expressions of Christianity. Slowly, there grew a new openness to Indigeneity. Perhaps, thought some in the church, Indigenous culture wasn’t evil after all.

In 1947, the denomination prepared a brief to Parliament on reforming the Indian Act, recommending the closure of residential schools and denominational day schools on reserves. The Home Missions board understood that the residential school system had failed. Over the next two decades, the church quietly divested itself of its interests in residential schools, dropping from 10 schools in 1946 to only six by 1960. In 1969, the United Church withdrew from its last residential school. While the church no longer ran the schools, it also went silent on the harm it had caused by participating in these institutions. As Joëlle M. Morgan points out in her 2018 dissertation, “Restorying Indigenous-Settler Relations in Canada,” the record also “seems to be quiet on the growth, development, and emergence of Indigenous leadership in the church.”

In the latter half of the 1960s, the United Church made what Morgan describes as a largely symbolic shift toward acknowledging the autonomy of Indigenous people by changing oversight of Indigenous church communities associated with reserves. Instead of being part of Home Missions, they were incorporated into the geographic Conferences and Presbyteries in which they resided.

Unfortunately, these well-intentioned decisions were made with inadequate local consultation and had major consequences for the Indigenous missions, now called churches. Cultural differences, language barriers and church-wide divisions between the rural poor and urban middle class made it extremely difficult for Indigenous church leaders to make their voices heard.

At the same time, the 1960s were an incredibly fertile decade for the advancement of civil rights. As the American Indian Movement and the National Indian Brotherhood, both founded in 1968, promoted change within Canadian politics, their calls to justice were also heard in the church. The United Church provided financial support for a series of meetings called the Indian Ecumenical Conferences, which drew thousands of Indigenous participants from across North America in the 1970s and ’80s. One of the lead organizers was Rev. John Snow, the first Stoney Nakoda minister ordained in the United Church, who became chief of the Nakoda-

Wesley First Nation in 1968. Indigenous people also began to abandon Christianity and explore their ancestral spiritual practices.

The church had a dawning awareness that it had failed its Indigenous members. Indigenous leaders began to step forward with concern, pointing out the ingrained racism within the denomination. Project North, an ecumenical coalition that helped Indigenous communities under threat from resource development, began in 1975 with United Church support. In northern Manitoba, an Elders council took shape to work on common goals and address problems in churches caused by language and cultural divides and by isolation. Rev. Stan McKay of the Fisher River Cree Nation raised these issues in a 1973 profile in The United Church Observer. “The Manual of the United Church has no concept of needs in the North, and the Church has failed to deal very effectively with leadership in these special conditions,” he said. “Some of the elders are ministers in every sense and should be so recognized.” McKay also spoke to the deep spirituality of Indigenous people. White people, if they listened, would have much to learn, he said.

The 1977 General Council decided to initiate a review of the church’s work with Indigenous people. A questionnaire distributed to all the Indigenous United Church pastoral charges frustrated some who felt it was yet another study at a time when action was needed. In 1980, the United Church began a series of national consultations with Indigenous leaders that would last for 25 years. Some Elders remember these consultations as a turning point in their experience of the United Church; perhaps there was a place for them in this church, and perhaps it was time for their voices to be heard in governing bodies. This began the movement to self-government and sovereignty in The United Church of Canada.

After the initial consultation in Saskatchewan, McKay was appointed in 1982 to the newly created position of national Native ministries co-ordinator. “There is a Native church now,” he told Mandate magazine the following year. “We can now tackle some of the difficult problems that face us and we are really prepared to begin dialogue with the United Church about concerns for training and about the inability of church structures to accommodate the uniqueness of the Native church.” Another action arising from these meetings was the formation of an Indigenous Presbytery in northern Manitoba and northwestern Ontario, known as Keewatin.

During this period, the conversation turned to opening community-based theological education centres. The first was the Dr. Jessie Saulteaux Resource Centre in Beausejour, Man., in 1984, named after the Assiniboine Elder who dreamed of a learning centre “run by Aboriginal People for Aboriginal People,” as Rev. Janet Silman describes it in “A First Nations Movement in a Canadian Church.” Within a few years, two more programs would open: a summer school for Indigenous ministry at the Vancouver School of Theology, and the Francis Sandy Theological Centre in Paris, Ont. (The latter amalgamated with the Saulteaux centre in 2011 to become the Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre.)

The demand for the first apology came during a 1985 meeting of the General Council Executive when the National Native Council was presenting a report. Alberta Billy, a We Wai Kai Elder and one of the presenters, shocked the Executive when she said, “I think the United Church owes the Native Peoples of the Americas an apology.” It was a definitive moment in United Church history. The Executive, realizing that an immediate apology would not suffice, began an education process with the broader church. The result was an official apology at the 31st General Council in Sudbury, Ont., in August 1986.

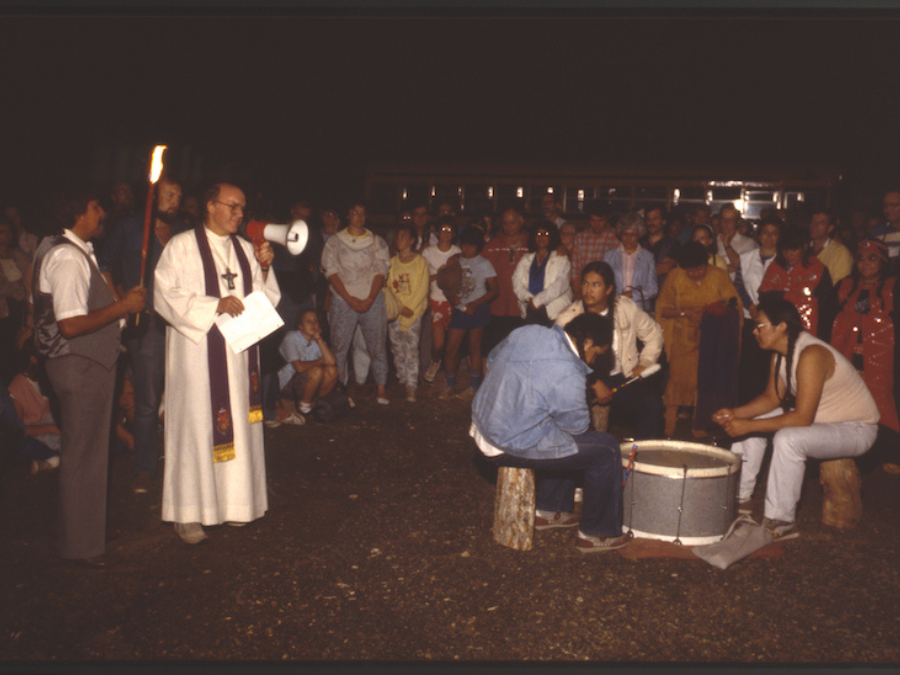

The debate before the apology was heated, with some commissioners worried it meant saying sorry for the Gospel and others concerned that acknowledging the integrity of Indigenous Christian faith would somehow dilute “real” Christianity. During these debates, the Indigenous commissioners withdrew from the court and reassembled outside near the Sacred Fire. Moderator Rt. Rev. Robert Smith came to the gathered Elders that evening and apologized: “We tried to make you be like us and in so doing we helped to destroy the vision that made you what you were.”

Afterwards, there was much celebration, yet the Elders were cautious. Just as there had been time for the United Church to form and embrace the apology, so too was time needed among the Indigenous churches. The Elders acknowledged the apology and took it back to their communities for discussion. Reactions were mixed. Some were pleased with the statement, while others were bitter about the losses of traditional ways and fractures within families.

One effect of the apology was recognizing the need for a new Indigenous Church structure. The challenge lay in fitting the circular model of Indigenous work into the hierarchical model of the dominant United Church. What emerged was the All Native Circle Conference (ANCC), constituted by the 32nd General Council in 1988. (It should be noted that not all Indigenous pastoral charges joined the ANCC. Some congregations chose to remain in their dominant church Presbyteries.)

These major structural changes were made while another crisis loomed. Throughout the next 20 years, residential schools became a major issue for both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous churches. The United Church had to recognize the ways that colonial thinking had forced Indigenous people to reject their own culture and traditions to become Christians. Moreover, survivors of residential school launched lawsuits, forcing the denomination to struggle through humbling legal processes. In 1992, McKay became the United Church’s first Indigenous moderator. Two years later, the church created the Healing Fund to help Indigenous communities respond to the damage caused by the schools. Donations were initially slow. Marion Best, a lay leader from British Columbia who followed McKay as moderator in 1994, said in a 2017 interview that “there was total fear in the national church that we were going to be bankrupted” by the residential school lawsuits. People weren’t yet ready to accept the church’s culpability.

One effect of the apology was recognizing the need for a new Indigenous Church structure. The challenge lay in fitting the circular model of Indigenous work into the hierarchical model of the dominant United Church.

Finally, in 1998, the United Church took another step. Moderator Rt. Rev. Bill Phipps delivered a second apology, aimed mainly at residential school survivors and their families. The 1998 apology acknowledged the pain caused by “this cruel and ill-conceived system of assimilation.” It also spoke of the physical, sexual and mental abuse students had suffered.

Reflecting on the apology several years later, Very Rev. Stan McKay wryly observed that “real change requires a great deal of focus that is not always evident in a white, middle-class church. We are still trying to deal with the [first] apology in many ways. What did the residential school apology mean in the sense that the previous one is still on the table?” Words mean little if not backed up by transformative actions.

In 2006, the United Church signed the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, acknowledging responsibility and committing to financial compensation and actions to promote healing and reconciliation. This gave the United Church a framework to live up to its promised commitments. One result of this agreement, which was also signed by the other denominations involved in the schools, was the establishment of the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Zigzagging across the country between 2010 and 2015, the commission invited survivors to share their experiences, often for the first time, and have their stories included in the official historical record. The stories of abuse amounted to nothing less than a cultural genocide.

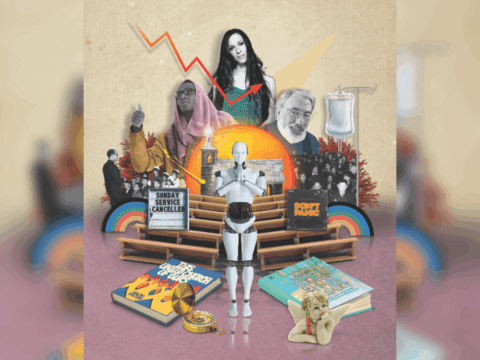

In the wake of the apologies and TRC report with its recommended actions, the United Church and Indigenous Peoples are in a delicate place again. While much excellent healing work has happened, much work remains. It is no longer sufficient to provide resources for healing — structural justice and sovereignty are a must. As Marie Wilson, one of the three TRC commissioners and a United Church member, told Mandate magazine in 2015, “One truth that the church must learn is the role it plays in undermining the relationship between Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal people.”

In recent years, the difficulties between Indigenous and dominant churches have continued. In the restructuring process that began in 2013, each Conference in the United Church met with the Boundaries Commission. Indigenous leaders were clear that they had fought hard to get the Indigenous structure of the All Native Circle Conference approved, and they were strongly opposed to its dissolution. The boundary commissioners heard their concerns and promised to return for further discussion. They never returned. In 2019, all Conferences of The United Church of Canada were dissolved and restructured into 16 Regions. ANCC, along with the others, was gone. The pain among Indigenous communities of faith was palpable. In place of the ANCC, the United Church held space labelled as the National Indigenous Organization, to be led by a National Indigenous Council. Unfortunately, nothing remained of the ANCC and its circles of responsibility. Again, the Indigenous Church was left to redevelop itself from scratch.

The last five years have been challenging. Redeveloping leadership structures has taken considerable time. Two National Indigenous Councils have been formed, each under very different approaches. The first was elected without regard for status or location in the country. The result was that many parts of the country didn’t have representation. The second approach focused on structuring the Indigenous Church. Like the ANCC, geographic circles were formed: British Columbia, Plains, Keewatin, Ontario-Quebec and Urban Centres. These five circles, in turn, appoint two people to the National Indigenous Council. The 10 individuals, along with a representative from the General Council Executive, are supported by the denomination’s executive minister for Indigenous ministries and justice. This is the National Indigenous Council. The Indigenous Church recognizes a second body: the National Indigenous Elders Council. Nominated by Indigenous communities, the Elders provide wise counsel when asked.

The National Indigenous Council of 2019 agreed that structure was necessary, and it requested changes to the Basis of Union to remove barriers to developing the Indigenous Church. General secretary Rev. Michael Blair offered a more radical solution: a pre-emptive remit that would clear the path to allow structural change without knowing the final shape of the Indigenous Church. Every Region and 80 percent of pastoral charges voted and overwhelmingly approved the change.

I remember the excitement when it became clear that the remit had passed with near-universal support. So many Elders and church leaders had worked for this moment and not lived to see it; a parade of their faces passed before me. The Indigenous Church no longer had to come to the dominant church for permission to make structural changes. The days of paternalistic control were over.

Yet, the first time conflict arose in the National Indigenous Council, some councillors reverted to asking the dominant church to intervene. While acknowledging the difficult circumstances, the general secretary stepped in last August and dissolved the National Indigenous Council. At a special meeting of the National Indigenous Spiritual Gathering last fall, Elders decided to take some time for healing from these actions. They also decided that the National Indigenous Elders Council would consider the design of the National Indigenous Council with the hope that a truly Indigenous solution could be found. Meanwhile, the United Church’s executive minister for Indigenous ministries and justice has been fired, the National Indigenous Council remains disbanded and the National Indigenous Elders Council is struggling with steps forward. The wider United Church is just beginning to comprehend the actions taken in its name. The resulting firestorm has yet to be resolved and will likely be an issue at the General Council this summer.

After 100 years of United Church spiritual leadership, where do Indigenous Christians and their communities stand today? Two steps forward and one step back. A pressing need remains for autonomous Indigenous leadership and the space to explore how to live out Indigeneity within the United Church. At this point, as the outgoing Indigenous representative on the General Council Executive, my view is that a reset is needed. My hope would be a gathering of Indigenous leadership, past and present, out on the land, where the design of the Indigenous Church could begin with ceremony, wisdom, faith and creativity. Most importantly, it is time for the wider United Church to step back and allow the Indigenous Church the autonomy promised in the church-wide remit. I, for one, look forward to the new Indigenous Church that will be resurrected.

***

Rev. Teresa Burnett-Cole, of Mohawk heritage, is the minister at Glebe-St. James in Ottawa. Her doctoral thesis explored Indigenous contributions to intercultural worship in the United Church.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s June 2025 issue with the title “A Journey to Right Relations.”