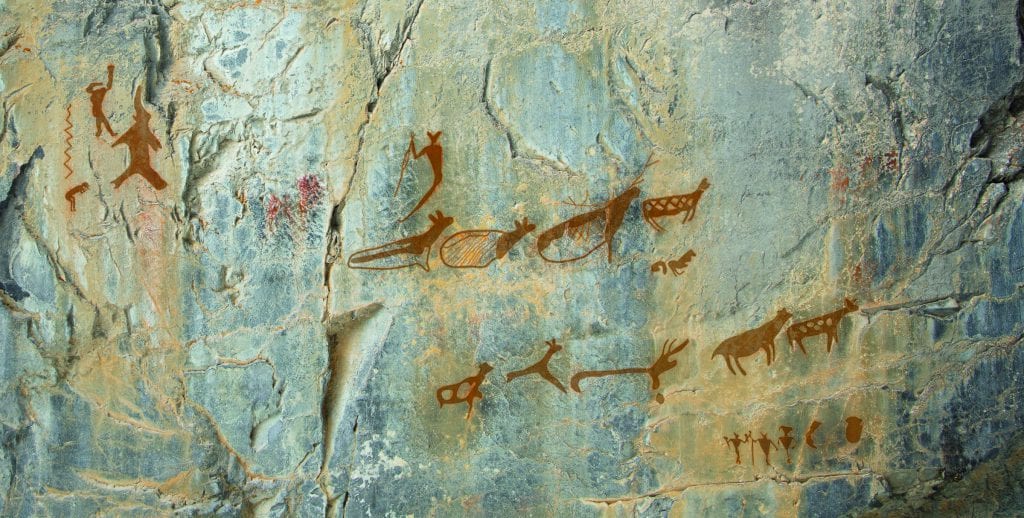

When Isaac Murdoch was a teenager, he would canoe to a cliff face that jutted out on Lake Megoog, 100 kilometres east of Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., as the crow flies. He went with the elders from his community, Serpent River First Nation, who taught him about the spiritual significance of the rocks. Centuries before, Murdoch’s Ojibway ancestors came here in times of war, famine and sickness to seek visions. They sat at the site for days, without eating or drinking, and they painted images onto the stone — animals, such as beaver and moose, and short lines that marked days spent fasting.

In this ancient place, called Waadgagaagu Aazhing (meaning White Raven Cliff), Murdoch could connect with the spirit of his ancestors. In the eyes of the provincial government, it is part of Matinenda Provincial Park, which spans almost 30,000 hectares and neighbours both Serpent River and Mississauga First Nations.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In 2017, Murdoch, then 42, decided to paddle out to the site once again. It had been 25 years since his last visit, and much had changed. Cottages now ring the lake, their boats shattering the calm. But what he saw at the sacred rocks shocked and saddened him. Many of his ancestors’ images had been covered over with spray paint. “When I was a child, it seemed like there were 100 of them,” says Murdoch. “Now, I can only count eight.”

Some of the graffiti appeared to be initials, and one read “SMILE” over a large happy face. Most striking of all was a giant Canadian flag painted on the cliff not far away. The vandalism was an affront to Murdoch’s heritage. He sees it as the equivalent of someone desecrating the oldest church in Canada. “It was quite heartbreaking,” says Murdoch with pain in his voice. “These sites are thousands of years old and hold spiritual significance.”

The images at Waadgagaagu Aazhing and many other pictograph sites were created with red ochre, often made by grinding a reddish-black mineral called hematite into a fine powder. Some of the drawings date back thousands of years. Rock art specialists have said they survived time and the elements because they are stains, bonded to the rock and coated with a clear “varnish” formed by minerals dissolved in rain-water that run down the rock face.

Pictographs (painted onto rock) and petroglyphs (carved into stone) exist for various reasons, but Murdoch, an artist who has researched rock art for 30 years, says their spiritual significance is a common thread — as is their vulnerability. They are threatened not only by wind and rain, but, more ominously, by members of the public looking to paint over the images or etch the sacred stone.

Modern spray paint binds tightly to rock, leading to some of the worst incidents of vandalism. In the past decade, rock art sites have been defaced and in some cases nearly destroyed in areas of British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec. Indigenous communities are left to mourn the loss of their ancestors’ knowledge as they grapple with the stinging and blatant disrespect of these ancient places.

“It seems like any part of our history, any proof of our existence, has been wiped out,” says Murdoch. He names the Sixties Scoop and forceful relocation of Indigenous children from their homes to residential schools as acts of cultural genocide. “There’s a relationship between what’s happened to us and what’s happening to our sacred sites.”

But protecting rock art is complicated — the sites are remote, spread out and intrinsically connected to their surrounding environment. Some are on land managed by First Nations, while others are on Crown land or situated in federal and provincial parks. They’re also considered “living sites,” meaning they are still visited by nearby First Nations and used for ceremony and spiritual connection. So who decides how to preserve them? And how can it be done without separating First Nations from their sacred sites? These dilemmas come with high stakes and no clear answers.

Two sites fervently protected by the federal and provincial levels of government and Indigenous groups illustrate the trade-offs of safeguarding rock art .Kinoomaage-Waapkong, or the Teaching Rocks near Peterborough, Ont., is a sacred site for all First Nations, but particularly the Anishinabeg, who have used it, who have used it for generations to preserve and share traditional knowledge. The area contains about 900 images, from animals to human and spiritual figures, carved into the relatively flat, undulating limestone on the southern edge of the Canadian Shield — one of the largest known collections of petroglyphs in Canada.

The site is still used today: every summer solstice, members of the Curve Lake First Nation honour the rocks with a ceremony. It is attended by up to 100 people, many of them non-Indigenous, whom the community welcomes. There is singing and drumming, and tobacco is offered to the land as a prayer.

Petroglyphs Provincial Park was created in 1976 and was declared a National Historic Site in 1981. The province discovered the surface of the rock was deteriorating, likely because of rain and groundwater run-off. The Ministry of Natural Resources decided the best way to protect the site would be to erect a building directly over top of it.

Large and easily accessible, the centre became an attractive tourist destination (it drew 17,500 visitors in 2018). People can enter the temperature-controlled building and circle the petroglyphs from a fenced-off viewing platform, guided by interpretive plaques. “To some archeologists, this is the image of preservation,” says Dagmara Zawadzka, a rock art scholar who has written about the controversy of protecting the Peterborough petroglyphs. “It basically sent a message to the general population: this is worth preserving.”

However, she says, Petroglyphs Provincial Park has also been heavily criticized by some archeological and heritage circles, as well as Indigenous people. Despite members of Curve Lake First Nation and other Indigenous people being able to access the site for ceremonial purposes, the building actively cuts off the petroglyphs from the surrounding environment. “That building was something we were not consulted about,” says Anne Taylor, a member of Curve Lake First Nation, who are stewards of the site. “Against our wishes it was done.”

First Nations have historically interacted with the natural world through respect and careful ritual observances, and many pictograph and petroglyph sites were chosen for the surrounding landscape. What settlers might consider natural formations and landmarks (a river, a cliff facing west, boulders) are perceived by First Nations as sacred. The pictographs themselves, then, are the focal point to a much larger spiritual place. “Rocks are grandfathers,” explains Taylor. “They carry the knowledge of the land, the history; they have been here and survived thousands of years and hold that knowledge in them.”

Taylor says you used to be able to hear the sound of an underground stream at the Teaching Rocks. The rock’s crevices are thought to be an entrance into the spirit world, and the sound of the water that flows beneath are the voices of her ancestors. If you listened closely, she says, you could hear their teachings. Whether because of the disruption of the bedrock during construction or the building’s mechanical air circulation, that sound is gone.

When asked about the building and the lack of consulation in the 1980s with Curve Lake First Nation, Gary Wheeler, a government spokesperson, said in an email, “Ontario Parks is committed to working with Indigenous peoples across the province to uphold its obligations with respect to Aboriginal and treaty rights and strengthening its relationships with Indigenous communities.” He added that the park and First Nation have had a joint committee to work on protecting the site since the mid-1990s.

Where the Peterborough petroglyph conservation is restrictive, Writing-on-Stone is expansive. This high-profile site in southern Alberta is known as Áísínai´pi, meaning “It is written” or “It is pictured” to the Blackfoot (or Siksikaitsitapi) nation. The provincial park has thousands of pictographs and petroglyphs (including a depiction of an entire battle scene), some of which date back 3,000 years. Writing-on-Stone has gained much attention from tourists, especially since earning a World Heritage designation last July.

The area spans almost 2,700 hectares — larger than Toronto’s Pearson Airport — and the park is separated into zones. Park supervisor Aaron Domes says tourists will only be able to wander most rock art sites with a guide. Otherwise, access is reserved for Indigenous ceremonies or traditional use.

Only a few places operate on the scale of the Peterborough petroglyphs and Writing-on-Stone. Some other well-known sites simply have plaques or signs to help tourists understand their spiritual importance to First Nations communities. The Agawa pictographs in Lake Superior Provincial Park, for example, are one of the most visited archeological sites in Ontario, attracting nearly 2,000 people last July and August. Each summer, two signs direct cars off the Trans-Canada Highway to Agawa Rock, where a Parks staff member greets visitors, who can buy an informational pamphlet for a dollar. Inside, a one-paragraph blurb asks tourists not to touch the images, which are up to 400 years old, but little is stopping them.

Across Canada, most of the estimated 3,000 rock art sites are left unprotected. They can be found along the shores of lakes and rivers and tucked deep into forests, away from major roads or residential areas, but exposed to potential vandalism. With no easy and affordable way to universally protect these sites, First Nations communities and archeologists are turning to the most obvious question: why does vandalism happen?

When Murdoch discovered the extent of the destruction to the pictographs of his ancestors, he posted the images on Facebook, which drew the attention of the media. In May 2017, the CBC published an article quoting Murdoch, and he received death threats. “They were angry because I wanted the Canadian flag removed, and I wanted the site to be off limits and under the jurisdiction of First Nations people,” he says.

Murdoch sees the issue of vandalism as land-based and inherently racist. “There is a larger psychology here,” he says. “You get rid of the sites, you erase the person’s history. It’s really a form of genocide.”

Jannie Loubser, an archeologist and rock art specialist, was hired last year by Alberta Parks to help restore some images at Writing-on-Stone that vandals had scratched up. (Even though the park tries to protect the art, deliberate destruction still happens.) He likens the restoration process to plastic surgery and says it can be nearly impossible to erase every sign of vandalism. Rather than risk damaging the original art, he aims to render the pictograph easier to see. “I think a common mistake is that people talk about removing the graffiti, but they don’t talk about [preventing] the graffiti,” says Loubser.

In his paper on the removal and camouflage of graffiti, published by the Bradshaw Foundation, an archeology resource, Loubser writes that the reasons why visitors decide to graffiti a site are difficult to pin down, “but probably have something to do with ‘domesticating’ untamed spaces.” This, he writes, includes scribbling down their own names or initials or those of loved ones, as well as faces, symbols, towns of origin, and dates of visits.

This is exactly how Kevin (not his real name) and his friends found themselves arrested and charged after defacing pictographs in the United States a decade ago. The three men, each in their early 20s, hiked into a canyon where they often hung out and spray-painted the rocks. He wrote his name and his friends painted “stupid shit about weed.”

Kevin swears they didn’t see the pictographs. However, he ended up spending five months in jail with an added five months on house arrest for wilful injury or depredation of property. His friends also served time, and each had to pay significant fines for the restoration. “[There were] no signs posted. We had no idea,” he says. “It gets me mad and upset still.”

Many visitors to rock art sites don’t know these places are sacred and are still used as spiritual places where First Nations communities connect to the spirits of their ancestors. When rock art sites are presented as relics of the past, this sends a message to visitors that the individuals who originally etched or drew on the stone were members of an extinct community and that the art no longer belongs to anybody.

While signs might help raise awareness, it’s impossible to place them at each site. Some experts feel the best solution to preserving rock art lies in education. If people are aware from a young age about the spiritual significance of the sites, they may stop vandalizing them.

This falls in line with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s call for schools to provide more detailed information on residential schools, treaties and Indigenous people’s lives both past and present. “Much of the current state of troubled relations between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians is attributable to educational institutions and what they have taught, or failed to teach, over many generations,” the report says.

Last year, the CBC charted the progress of provincial updates to Indigenous content in Canadian schools. According to its research, while some curricula have made significant improvements, overall progress is spotty. Many teachers have been left to decide how much and how in-depth to educate public school students on Indigenous history.

Robert Louie, a Lower Kootenay Band elder in British Columbia, says he leads “Heritage Tuesdays.” These sessions teach young people about the history of First Nations and their ongoing spiritual connections to the land. Louie is trying to make up for lost time and knowledge: “Much was lost to the Sixties Scoops and the residential school scoops,” he says. “Nobody has the teaching I did.”

When Louie was seven years old, he ran away from the residential school where he had been placed. He walked over 150 kilometres, a distance that took Louie 21 days. He avoided the highways and stuck to rugged mountain terrain, using his ancestors’ astronomical knowledge and eating edible plants.

Louie made it home and grew up with his grandparents, who shared the knowledge of his ancestors, including that of the many pictographs that surround his community. He hopes by helping young people understand Indigenous history and the value of rock art, the public will better protect them. “When you tell a story, it comes to life, and it’s no longer a story. It’s a living spirit.”

Many of his ancestors’ images are now pocked with BB gun bullet holes or smeared with black paint. The pictographs are on the shores of Kootenay Lake and are a destination for tourists, but they are not actively protected. Louie’s grandparents never saw the vandalism; he believes it would have made them angry. “That’s our heart and soul. The pictographs are the roots of who we are.”

Understandably, some Indigenous communities don’t trust that education will be enough and hide the existence of sacred rock art sites known to their community. “The more people you tell about a sacred site or educate about it, the more they go there and the more damage gets done to them,” says Murdoch. Even though only a small percentage of society would do this, he adds, his community can’t afford the risk of revealing some pictographs that remain hidden from the public. “People will go there, they’ll take the sacred items that are there, and they’ll be spray-painted.”

For now, the images at Lake Megoog remain exposed to the elements and human actions. In the few years since the vandalism was covered in the media, different ideas have been floated on how to better protect them from further harm.

Chief Reg Niganobe of the nearby Mississauga First Nation (who also have a spiritual relationship with the pictographs) is open to educational signs at the lake’s boat launches to teach visitors to respect the sacred rock art they might come across. Murdoch has made presentations to young people and has reached out directly to cottagers. “We need to go door to door and hand out flyers and say, ‘Hey look, with living here comes responsibilities to make sure these sites are protected,’” he says.

Murdoch has faith that the images at Lake Megoog will outlast the graffiti. He can already see the spray paint fading, the original images poking out from beneath. But there is always the possibility that the images could be attacked again, and eventually covered up forever. “We’ll make more,” he says defiantly. “We can’t be erased.”

This article was first published in Broadview‘s April 2020 issue with the title “Under threat.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.