I learned what the word atheist meant when I was eight years old. My older sister was a smart-ass and decided she was going to be one because religion seemed “dumb.” I felt the same way.

I understood religion growing up as a list of rules: if I asked my mom if I could go to a friend’s house for a sleepover, or if I could wear a dress without stockings, her response was always, “No, that’s against our religion.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

That was enough for me to reject not just Islam, but religion entirely. In retrospect, I have sympathy for my parents, who were Pakistani immigrants afraid of what the West represented; how it seemed this new world could only corrupt us. For them, religion probably did feel like protection — they just didn’t know how to wield it like a shield, as opposed to a weapon.

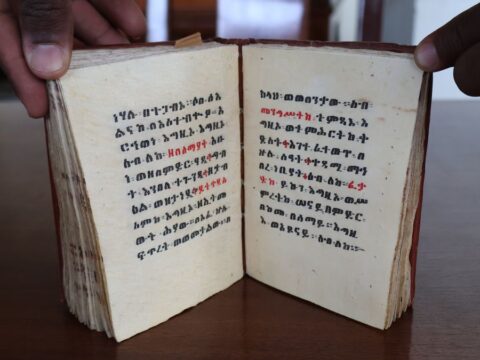

From the time we were six years old, my mom tried to get me and my sister to learn and recite the Quran. I was confused: What was this giant tome? And what did it have to do with me? The beautiful curves and slants of Arabic and Urdu escaped me.

At school, it was tougher. Even though I grew up in Scarborough — a very South Asian part of Toronto — there weren’t many other Muslims in my class. All I knew were the kids who celebrated Christian holidays because we all had to sing carols during Christmas and hunt for eggs on Easter. The school board didn’t acknowledge a single South Asian holiday, so clearly Islam — or Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism — weren’t considered to be as valid or interesting.

More on Broadview:

One time, I wore the mini-Quran necklace my late uncle had given me (and told me never to take off) to school. Kids asked me what it was and when I explained, they laughed. So I ripped it off at recess to rid myself of the shame I felt about being Muslim. That shame followed me for years. As a teenager and later, as an adult, I desperately wanted to avoid being othered. The best alternative, it seemed, was to be an atheist. But my beliefs started to change one and a half years ago, following the death of my aunt, Shahzeena Yousaf.

Shahzeena was like my second mom. In South Asian cultures, aunts, uncles and cousins can be as close as your closest. They’re always there and probably live nearby, if not downstairs. She was there for my birth and those of my siblings.

Less than two months before she died, she suddenly became very sick. Doctors couldn’t figure out why, but they were pretty certain it was cancer. While the rest of us were shocked, she was somehow okay. She wasn’t confused, scared or worried. But I also remember how, no matter how sick she was, she remained regimented about listening to a set of prayers multiple times a day. For a few days, she got better. Then she got worse than she’d ever been, and then she was gone.

My aunt was always the only truly religious person in our family: she prayed five times a day, she ate halal meat, she covered her legs and arms. And I saw how it gave her peace in the hardest moment of her life. Her death was the first time I’d ever experienced the loss of someone close to me. My entire family, especially my mom, fell into a deep grief. For a long while, I couldn’t think about anything else. So, I turned to prayer, reciting the ones my mom taught us when we were younger that I hadn’t forgotten. I found the old necklace my uncle gave me and hung it up in my apartment as a kind of protection. For the first time in my life, I was starting to understand why some people find safety and security in faith, and how it can guide us through difficult times.

A few months ago, while scrolling on TikTok, I started to notice a wave of non-Muslim and non-practising Muslim users who, like me, discovered Islam as a way of coping with grief. The world feels more fraught than ever. As of writing this, over 39,000 Palestinians and 1,400 Israelis have lost their lives since the start of the war in Gaza. The conflict has inspired many to read the English translations of the Quran, or to give fasting a try ahead of Eid this past April. Some did it for those who couldn’t in Palestine and others participated as a way to combat rising Islamophobia.

Nefertari Moonn, a Tampa, Florida-based comic artist and fashion designer, turned to Islam after being inspired by the resilience of the Palestinians. “I was taken aback when I saw that, in the face of such horror, they still got down on their knees and screamed for Allah. I imagined myself in that situation and wondered if I would do the same for who I worshipped at the time, would I truly call on any god if I saw my children the way they had to, or would I lose my faith completely?” she told me.

Moonn started learning about Islamic and Palestinian history, and began reading the Quran (borrowed from her husband, a Muslim), which she said often moved her to tears. “I found more than I was looking for,” says Moonn. “I found peace, I found love, I found understanding.”

At a time when Islam’s branding couldn’t be worse, like Moonn, I feel more connected to it than ever. In my rediscovery, I also gave fasting a go, have been reading an English translation of the Quran, and learning more about contemporary Islamic traditions and practices. I’ve found a new community, another side to my identity, and a spiritual system that grants me a sense of comfort in knowing it did the same for generations of my family. What I didn’t expect is how this experience has helped me bond with my mom. We’re already close, but she has always felt a little bit heartbroken that her children didn’t take an interest in religion. I still remember her joy when I told her I’d been learning more about Islam. She said she would tell me all about it and answer all my questions — better yet, we would do parts of it together. We would fast, we would learn new prayers, and we would find poetry and art that connects us. And we would do it for my aunt, because she couldn’t anymore.

There’s still a part of me that is afraid of judgment from those who’ve had their faith all their lives; that they might serve me some side-eye for being a late joiner. But I know my aunt is prouder than ever of me, and has been guiding me every step of the way.

My mom recently told me, “You can only find religion when you’re ready and open.” And now that I’ve found it, I’m finally proud to call myself a Muslim.

***

Sadaf Ahsan is a Toronto-based writer and editor. By day, she’s a journalism instructor at Humber College. By night, she co-hosts Frequency Podcasts’ The Reheat.