(RNS) — Three religions. One building.

The concept could be profoundly simple or particularly complex.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

For Berlin’s “House of One,” it’s turning out to be a bit of both.

Dubbed “the world’s first churmosqagogue” by one Reddit user, the House of One — “the world’s first hybrid church-mosque-synagogue” — will break ground in Berlin on May 27, 2021.

By then, it will have been a project 12 years in the making, at an expected cost of at least 47.2 million euro (C$72.5).

Its designers and leaders hope it will be used by Jewish, Christian and Muslim members as a place to pray, worship, gather and, perhaps above all, host a dialogue among their respective religions and with society at large.

But while the House of One is intended to show that peace is possible among — and through — the world’s so-called “Abrahamic traditions,” some Berliners regard it as an overwrought symbol that has little practical purpose in the heart of one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities.

More on Broadview:

- 7 Muslim-positive TV shows to stream right now

- How helping a refugee family taught this congregation to be the church

- ‘Photography was the way that I could share different Indigenous realities’

The idea for the House of One came to Protestant pastor Gregor Hohberg after he discovered the ruins of Berlin’s first church. The late Romanesque building, dating to the 13th century, had been destroyed and reconstructed repeatedly, most recently in World War II, before being torn down during the Cold War.

Hohberg wanted to honour the history of the place with a new building, but not just another church. “It had to be something that spoke to Berlin, to our world today.”

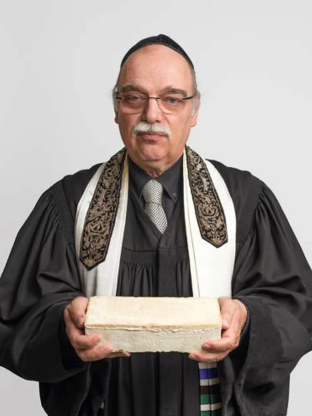

With the support of his parish, Hohberg sought out Jewish and Muslim partners. First came Rabbi Tovia Ben-Chorin, later replaced by Rabbi Andreas Nachama, a former rabbi for the American military synagogue in Berlin’s southwest. Then, Imam Kadir Sanci, of the Forum for Intercultural Dialogue, joined them.

The three began the slow process of getting to know one another and raising funds for the massive building project. “At first we were conversation partners,” said Sanci, “then we were colleagues, and now we are friends.

“The focus was on togetherness, spending time together, learning together and cooperating on a major construction project,” he added. Hohberg chimed in, “and by cooperating on a major construction project, you learn a lot about people through that!”

The three have grown to become more than just friends, said Sanci, but “Seelenverwandte” — or “soul relatives,” who plan to seal their friendship at a groundbreaking ceremony at Petriplatz, in the center of Berlin, in May.

“On our way to peace in heaven, we have the chance to create that here on earth,” said Nachama, “but that’s not to be taken for granted. You have to work at it and build a place for peace on earth.”

The House of One’s architectural design has received lots of attention over the last decade. Its layout provides equal space for Jews, Christians and Muslims to pray, worship and gather under its roof. But the emphasis is on the spacious “Begegnungsraum,” or meeting place that connects them, where people of all backgrounds will be invited to build relationships of peace like the one Hohberg shares with Nachama and Sanci.

“In this room,” said Sanci, “the House of One becomes more than a house of prayer, but a house of understanding.”

The House of One is not the first attempt at housing the Abrahamic faiths together. The House of Religions in Bern, Switzerland, opened in 2014, and the Tri-Faith Initiative in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2020. The Temple of All Religions in Kazan, Russia, and the Abrahamic Family House in Abu Dhabi, U.A.E., are both under construction. Other similar meeting places in Haifa, Vienna, and elsewhere have been compared to the House of One.

“This idea is exportable,” said Nachama. “The House of One is just a ‘test-case’ for how we can actually build peace.”

In Tbilisi, Georgia, Bishop Malkhaz Songulashvili, the metropolitan bishop of the Evangelical Baptist Church of the Republic of Georgia, drew inspiration from the House of One for his own “Peace Project,” which locals also refer to as the House of One.

Established as the First Baptist Church of Tbilisi in 1867, the Peace Cathedral is the mother church of the Evangelical Baptist Church of Georgia. “In the course of its history, Peace Cathedral has repeatedly taken bold stands in support of oppressed minorities,” said Songulashvili, “even as the church has suffered periodic harassment from religious extremists.”

Painfully aware of religion’s role in violent conflicts, such as the recent nearby Nagorno-Karabakh war, Songulashvili’s congregation took the bold step of constructing a mosque and a synagogue attached to its church building, “creating a spiritual home for Abrahamic faiths, including both Sunni and Shia Muslims,” he said.

Bishop Ilia Osefashvili said that without the House of One in Berlin’s support, the project could not proceed. More than money, he said, “a project like House of One helps us to build bridges of peace and friendship with other religions. Without it, alienation and hostility are difficult to overcome.”

The House of One has also established a formal partnership with “the House of Peace and Religions” in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic, a majority-Christian country where faith has fueled conflict in recent years.

Berlin’s House of One has worked with the country’s cardinal, Dieudonné Nzapalainga; the former president of its Islamic Council, Imam Oumar Kobine Layama; and president of its Evangelical Alliance, Pastor Nicolas Guérékoyaméné-Gbangou, to further efforts at unity.

For all its influence abroad, however, the House of One has faced criticism at home. While the House of One’s intentions are in the right place, various multifaith activists say, the details have been problematic. Some have complained that the exorbitant cost could have been better spent.

Dagmar Apel, pastor and consultant on migration and integration for the Protestant Church in Germany (EKD), expressed concerns that the House of One will showcase its founders’ hopes more than bring faiths together in the city.

“We need something that speaks to Berlin on the inside and not just on the outside,” Apel said. “The design is beautiful, but we need a place that is more than a meeting point for tourists, but for true religious exchange.”

Apel, who pastored in Berlin’s diverse Neukölln and Kreuzberg communities, said interreligious work is difficult in the city, especially given Germany’s “disastrous national history.”

Berlin, with its diverse, young international mix, can be a place where “Germans can develop a better intercultural competence,” she said, but added that “the House of One lacks grassroots support.”

Apel and others fear that Sanci’s association with Fethullah Gülen, the Turkish imam who founded the Hizmet Movement, will deter many of Berlin’s Muslims. Hizmet describes itself as a “faith-inspired civil society” but has run afoul of the ruling AK Party in Turkey for its supposed political aspirations. It is a lightning rod in the broader German Muslim community, particularly for its large Turkish minority.

“The Gülen movement is not representative of Muslims in Berlin,” said Apel, “and could never be because of the political situation.”

Moreover, said Apel, “where are the Asian religions? The spiritual-but-not-religious? You can’t have a ‘House of One’ without involving people of other religious groups.”

Michael Bäumer, the managing director for the Berlin Forum of Religions, agreed that the House of One missed an opportunity by not speaking to Berlin’s broader religious diversity.

“It’s a difficult task to bring different people together for dialogue,” he said, “and a lot of religious people in Berlin aren’t really interested in the House of One.”

As a Buddhist, Bäumer said, “I don’t know why I would go there. They have a lot of work to do to reach beyond the three religions.”

Bäumer has cooperated with the House of One on different multifaith initiatives and admires the leaders’ meaningful multifaith relationship.

“I like the people involved. They are good people and we often talk together. I really like them,” but, when the House of One is finally finished, Bäumer said, “the important question will be whether they can open their relationship of peace to other persons of belief.”

What we have here is the chase for Universalism. Where in Scriptures do we find support of this? The Israelites were commanded to follow “no other gods”. Christ told His followers “no one comes to the Father except through Me”.

How can a fallen world achieve peace? Obviously it cannot.

As much as we respect our friends who are Jewish and/or Muslims, we are called to be separate from the world.

Just reading this article show the many flaws that comes when one tries to mix Christ with the world.

Regardless of the resistance to the undertaking, I think it is wonderful that there is a start to understanding each other and becoming friends. Whatever our religious belief, in this world we have have to accept and understand our diversity. Love thy neighbour.

I think Rabbi Nachama said it well: “On our way to peace in heaven, we have the chance to create that here on earth.” We are called to be ministers of reconciliation and peace as we seek the kingdom, here and now.

This is a beautiful example of building peace through relationship and understanding.

I understand how some may feel threatened by this level of “tolerance” as if it challenges our faith but it should not. It strengthens our faith in a God who is bigger than us and our limited understanding of him. He does not task us with the responsibility of judging or defending but to love our neighbour and to seek the kingdom of shalom.

What makes Christianity different? How does one reconcile 2 Corinthians 6:14-15 and John 15:18-25?

1 Corinthians 6:1-3 are we not called to judge? 2 Corinthians 10:5 and 1 Peter3:15 tells us to defend the faith.

I wonder if it is possible to take the best of the teachings of each faith and begin a dialogue without dogma. Some of us take our religious teachings literally; some accept them metaphorically, some accept them as mythology. As well, some elevate our teachers to be somehow equal with God. If we could just focus on the good things such as love, sharing, forgiveness, acceptance, and the rest; that would be a good place to begin but I fear it would soon deteriorate into the less important beliefs and the “cherry picking” that so often happens to justify one’s own opinion.

Spirituality, not religion is the answer but religionists wouldn’t agree. We have to envision the idea of God as being beyond our understanding but still being our creator; a symbiotic relationship, or as theologian Marcus Borg put it, “Panentheism…” God in everything and everything in God. When we can reach that place, we can have a beginning. I don’t hold out much hope, though.