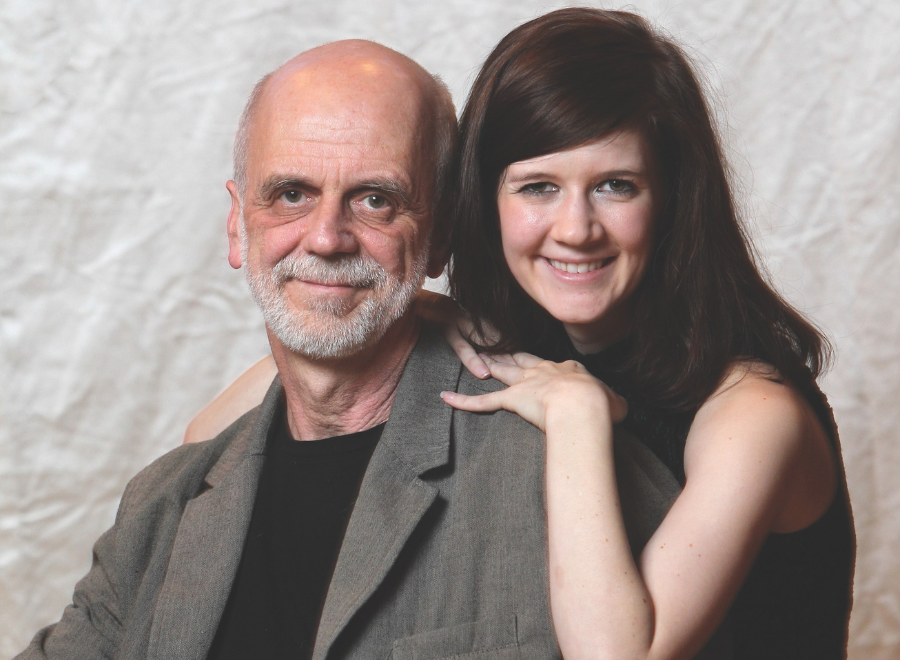

In late December 2009, our daughter’s heart failed. Completely. She was 26.

In the hours, then the days, weeks and ultimately months that followed, I grew to understand, as never before, the importance of prayer — its centrality not just to our spiritual lives, but to life itself. Christian prayers, Muslim prayers, Jewish prayers: anything, anyone, anywhere. Prayers held us. This isn’t metaphor; the holding was tangible, physical. They provided ground beneath us.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Kristin had been ill for several weeks, but it was the height of flu season. H1N1. Repeated trips to emergency resulted in repeated dismissals. Just the flu. An emergency nurse said there must be something wrong with the equipment — it kept showing impossibly low cardiac functions.

But it wasn’t flu. It was a heart so weakened that no one knows how she kept going. At first it was all a bewildering rush. No blood pressure. No pulse. An ejection fraction of six (50-plus is normal; under 25, heart failure). “We’ll try to save her limbs if we can.” Her extremities had not had blood for several hours. An image of my daughter without arms and legs formed in front of me, but fortunately just as quickly dissipated.

At this point, the doctors didn’t know my daughter — one of the most stubborn vertebrates God ever created. And they didn’t know, nor did we, that God’s hand would be so clearly in this. That this was the beginning of a journey, not the end, through a landscape of hope, not desolation.

Two heart surgeries in the first 24 hours, the second installing a ventricular assist device (VAD), a mechanical heart pump that would keep her alive while waiting for a heart transplant. Impossibilities everywhere: her blood vessels had all collapsed, they couldn’t get a line in and so couldn’t get readings, couldn’t administer the strong drugs they needed. She should have been unconscious but was inexplicably awake, lucid and talking to her brilliant, kind and equally stubborn surgeon. He was not going to lose her, he said in the operating room, line in or no line in, readings or none. Instead he trusted her voice to lead him, conscious when she ought not to have been. Together they enacted a miracle.

Meanwhile, the church had gathered to pray. Knox United is an old church in the heart of Winnipeg, now a neighbourhood of refugees and immigrants mostly. At that prayer gathering, I later learned, they started in that respectful but slightly insipid way typical of United Church folk, as if we were disturbing a grumpy father reading his newspaper. Then Afaf, a wonderfully strong Sudanese woman, got up, stamped her foot a bit and said in a large voice, “God, now you got to step up to the plate for Pastor’s daughter.”

But I knew nothing of that at the time. All I knew was what was in front of me. All I could do was mentally utter, “I trust you.” Not much of a prayer, perhaps, but it was real. It wasn’t piety or faith. It was simply my only option.

The news from the surgery was good. Mostly. The pump was working, she was alive, but there’d been a large clot — there was a chance of stroke. They would keep her unconscious for several days.

Then the slow awakening. The brain scan showed seven strokes. The Most Annoying Neurologist (MAN) poking her: “Definite paralysis, blindness on one side.” But the MAN didn’t know our daughter, nor, apparently, our God. I remember going to the chapel to pray, intending to scream, to curse at God, but all that came out was, “Is this the best you can do?” The rage wouldn’t rise. Instead I heard Job: “Though he slay me, yet will I trust him.” This was unsettling — I’d always been good at raging, doubting. But in that moment, that place so infused by prayers, lack of faith was not an option.

The holidays had ended and the main cardiac team had returned. She was young, they reassured us; young brains could heal. We had to wait, to pray, to send positive thoughts. And bit by bit, our daughter and our God defied the MAN.

Days passed in hours, hours lasted for weeks. People rallied around us. Someone put a cooler on our front porch — friends could put meals in there. We’d arrive at home, open the cooler and find a feast. Elijah fed by ravens. We were being held, fed by the hands of God, of friends, of family. Prayer became a thick membrane surrounding us, an amniotic fluid, almost tactile.

Sometime after the initial crisis, I started craving dysfunction: “God, I need something. Maybe booze — what about starting drinking again, God?” Before the thought was half-formed, I knew that would be a disaster, knew where that road led. Then I thought, “Smoking! That’s what I should do, God. I loved those American Marlboros.” But that wouldn’t work. Kristin would smell it, and she detested smoking. Nix cigarettes. Then a flash of clarity — a pipe! “C.S. Lewis smoked a pipe, God, and you liked him, right? That’s it — my little Irish pipe must be somewhere.” Then I remembered: I’d found just the stem a few years ago and pitched it. “Please, God, I need something. I’d like a pipe, but you’ll have to get me one somehow. No way I’m going to pay for one (who knows how much those things cost today?).”

This was the middle of the night in the chapel, and I was only half-serious. I’d been spending nights at the hospital, heading home at dawn to sleep. Mary, my wife, would come up for morning rounds. It was one of those astonishingly cold January dawns in Winnipeg, the sky clear and still. As I stepped onto our porch, I saw it on the table beside the front door: a pipe. A used one. I reached out, scared to touch it. The moment I did I could feel God laughing and a great warm voice saying, “You dumb ass, if I can do this, you think I’m not gonna take care of your kid?” I picked up the pipe and told no one about it for months.

I wasn’t actually going to smoke someone else’s pipe (yech). The point, I knew, wasn’t the pipe, but the warm enveloping joke that held me, and the promise it contained.

Days were spent in the waiting room with friends and family, the atmosphere warm and thick with a strange sense of well-being. Gratitude was inescapable — what else could one feel? We were so . . . blessed. The medical team all became part of this astonishing circle of love. Prayer was no more an option than breathing. It was as if we were beyond fear, beyond rage, beyond demanding, beyond begging. Prayer was holding on, repeating, “I trust you. She is yours.”

Days turned into weeks, to months and ultimately to years. It would be over two years before Kristin would receive her new heart. Two years on the VAD. After miracle comes adaptation — walking it out. She recovered in the hospital for eight weeks. The strokes had their impact. She needed therapy: physio, occupational, speech and language. And in all this her stubborn spirit turned indomitable. Her joy was infectious. She was grateful for each nurse, for the surgeons, for the ward clerk who called her beautiful and held up her pants as he took her for walks down the hall.

She could have seen herself as a victim or fed on resentment. She’d been an actor; would she act again? She could have allowed fear to overwhelm her. After all, she was being kept alive by a couple of batteries — disconnected she would die. But fear could find no toehold in her mind. Over the next few months, the reason for this became clear: gratitude cannot collocate with fear.

Rather than an emotion, fear might be more like a force, a vortex that saps the vibrancy of all emotions — joy, confidence, even sadness. Engage or argue with it, and it grows. But choose gratitude and, for whatever reason, fear dissipates, dissolves.

We could see it in her. Her gratitude at being able to walk 50 metres down the hall, for being able to play cribbage with her uncle, for laughing with her sister, for the amazing VAD machine that would keep her alive. She could have fixated on how she now had a wire coming out of her belly, had to carry around seven-pound batteries in a rather ugly vest (which she would later ditch for a Coach bag). Instead, she chose gratitude.

She could have been afraid of the machine. She had no reserve in her heart. If the batteries failed or became disconnected, she would immediately lose consciousness. She couldn’t be alone, even for a few minutes. But there was no room for fear. Did she have to will it away or kick it out of her inner room? I don’t think it ever got into the room. Gratitude was already there.

We saw how contagious positive thinking can be, saw it spread among Kristin and the other VAD recipients. Elaine had received her VAD a few months before Kristin and was also awaiting transplant. That spring she had a “dry run.” Airlifted to Edmonton, adrenaline pumping, to get her new heart, only to be told, “Sorry, the heart’s no good.” This happens. All the waiting, praying, hoping — dashed. How might you react? Kristin’s eyes widened as she listened. Elaine got to the point where the doctors tell her the donor heart was no good. Then Elaine smiled and said, “So I told them, well, that’s fine. I don’t want a bad heart; I want a good one. Call me when you get a good one.”

She’d turned disappointment around with laughter and grace. No room for resentment or self-pity. Positive energy transferred from Elaine to Kristin, and she in turn passed it on to others.

Gratitude was born for me in that helplessness of the first few days, when everything depended entirely on miracle. Faced with utter helplessness, one has only two responses: anxiety or relaxation. Everything is in God’s hands.

Slowly, a new normal emerged. Kristin came to live with us, her bedroom equipped with all the necessary machinery. Nothing could stop her. At the gym, strengthening her body for transplant. Speaking on organ donation: in schools, to community groups, on CBC — anywhere. She often said, and meant it utterly, that this was the best thing that ever happened to her. It taught her gratitude. And hope. Pushing the limits of the possible, she eventually convinced her medical team to let her move out on her own. Her apartment was about five minutes from our home. In the meantime, life slowly returned to a new normal for Mary and me too. We started back to work.

If you’re facing a difficult situation, there is no better place to be than among refugees, survivors. They know the power of prayer, the cost of hope. Sally, a community member, had escaped the rebels in Sierra Leone, taking her daughters and sons. Not all made it. We were chatting. I said I’d always wondered what would happen if you had to face your greatest fear. What would it be like on the other side? Would there just be new fears? Instead I found that it was simply quiet. Not peaceful exactly, just quiet. Her eyes fixed on mine. “I know that quiet, Bill. I know it very well.”

The phone rang at 11:30 p.m. on Jan. 6, 2012. It was Kristin, saying that Ottawa had called with a heart offer for her. I thought she was joking. Not my most stellar moment as a parent. Mad dashing, gathering, packing. Within two hours, we were on an air ambulance.

Have I mentioned Kristin’s love of shoes? A love inherited from my mother, who was in her 80s before she gave up heels. Kristin’s four-inch stilettos were in her bag.

Within six hours, we were at the Ottawa hospital and she was getting prepared for surgery. The removal team was working in Toronto at the same time. Final word on the suitability and health of the donor’s heart would not come until seconds before it would be transferred to Ottawa. Usually the patient is sedated for this. Kristin would have none of it. Didn’t want to wake up, she said, to learn she’d simply had a nice nap. Waiting in pre-op, she joked with the nurses. Word came that Kristin wanted to see her mom. Then she asked for her sister and me. She’d been regaling the nurses with tales of shopping and shoes. So much laughter. Then the news. Heart was good. Final prepping and off they went, Kristin loudly singing Achy Breaky Heart, the nurses dancing her stretcher toward the operating room.

Hours passed before the surgeon came out. It had gone well. It was a great heart, we learned, a perfect fit. As soon as he took the clamp off, the heart started beating on its own. It seemed very happy in its new home, he said.

Within hours of Kristin’s waking, the nurses helped her stick her still-puffy feet into those tiny shoes with magnificent heels and she walked — just far enough, but she’d done it. Resurrection was coursing through our veins.

I’d assumed that the Ottawa time would be prayerful, spiritual. Yet once there, I couldn’t pray. I felt suspended. Not angry. Not afraid. Not anything. Just there. I tried repeatedly, went down to the chapel. Nothing. I returned to the waiting room and sat. Hour after hour. Not praying. Not even thinking. I just kept saying, “Listen to their prayers, God.” I knew the church and community and so many others would be praying. It was as if I’d forgotten how.

I think it was being separated from community. I needed to know they were somehow within touching distance. Without them, part of me was disconnected. I could not be fully me. When I returned, I could pray again. But it was different, less anxious, less insecure. I slowly began to recognize how much had changed inside.

I’d always separated death and resurrection into two distinct processes. One bad, the other good. I learned they are parts of the same experience, the same process. The heart failure was a blessing, just as the heart transplant was. For hours in that waiting room, as the transplant was unfolding and afterwards, a conduit opened between our family and the donor’s family; their pain, their grief flooded our hearts. We wept with our joy and their sadness. Joy and pain were immeasurable and simultaneous.

After resurrection came the challenge of living in this new post-resurrection state. For Kristin this meant freedom (jumping in the shower whenever she wanted!), but her bursting liberation was accompanied by a suppressed immune system, a daily cocktail of meds, biopsies. Still a bit bewildered, we walk on — Kristin ahead in her heels, Mary and I trying to catch up. Emmaus can’t be far ahead.

Bill Millar is a pastor at Knox United in Winnipeg.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s March 2013 issue with the title “Living miracle.”