This story was first published on Religion News Service on June 26, 2020.

(RNS) — Shaykh Hassan Lachheb remembers first dreaming of hajj as a child, looking at small Polaroid photographs of his father at an airport in his native Morocco as he left for the holy pilgrimage to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia, one of the five obligations required of devout Muslims. Lachheb determined then to make the journey one day himself.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Lachheb, now president and co-founder of Tayseer Seminary in Knoxville, Tennessee, realized his dream many years later. For the past five years, he has led groups of American Muslims on twice-a-year trips to Mecca during hajj, which takes place in the Islamic month of Dhul-Hijjah, and umrah, a non-obligatory pilgrimage performed any time of year.

“Hajj is the fullest manifestation of what Islam is,” he said, “in regard to spirituality, in regard to rituals, in regard to our connection to history and how deep our history is.”

But this year will be different.

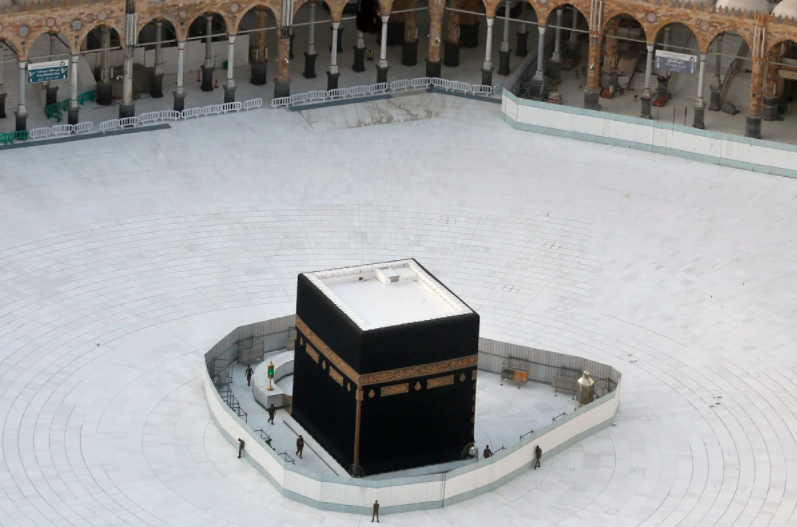

Earlier this week, the Saudi government announced that international visitors would be barred from hajj this summer out of concern for the coronavirus pandemic. Only about 1,000 people living in Saudi Arabia will be allowed to participate in the weeklong ritual, which begins July 28. The gathering typically draws some two million people from around the globe.

More on Broadview: A call to prayer brought me closer to my father

As early as March, Lachheb said, his group realized that their trip was threatened by the spread of COVID-19. Officially cancelling the trip, however, brought sadness. The pilgrimage has been disrupted in the past by wars and pandemics, but this year marked the first time in history that the two holiest mosques in Islam, the Grand Mosque in Mecca and the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, have been closed to the public simultaneously, he said.

Seeing images of these deserted holy sites — particularly around the Kaaba, the black cube that Muslims circumambulate during hajj — was a spiritual shock. “When you see it completely empty, it’s like our hearts are empty,” he said.

The uncertainty in recent months about whether hajj would go on has troubled many of those who planned to go, said Khalid Latif, a chaplain at New York University who has led hajj and umrah trips for students, faculty and NYU’s neighbours for the past three years. “I think you’d find some Muslims feeling some relief that they just know what’s happening,” he said.

But many may not be able to simply say, “next year,” said Latif. In addition to the expense — his trips with NYU cost up to US$10,000 per person — not everyone can easily arrange to take time from work, never mind cover care for children or parents.

Though hajj is considered an obligatory ritual for all Muslims who are healthy enough to make the trip and have the means, preservation of life supersedes all else.

For American Muslim converts, however, the hajj is more than the fulfillment of a sacred ritual. For all Muslims, hajj represents a fresh start when all past sins are forgiven, but for many Americans, it’s the first chance to experience a completely Muslim environment.

“We represent about one percent of the population,” said James Jones, vice chair of the Islamic Seminary of America in Richardson, Texas, who embraced Islam in 1979 and went on pilgrimage in 1992. “But there, everybody’s Muslim, and especially for the convert, that’s the first opportunity to be in a place where everybody’s Muslim.

“I don’t have to worry about what I’m eating, I don’t have to worry about offending anybody by saying, ‘assalamu alaikum, peace be upon you,'” Jones said. “There’s that sense of ease when you’re around Muslims. Everybody’s praying five times a day and nobody’s complaining about the call to prayer.”

Jones pointed out that Islam teaches that, since people are judged by their intentions, those who planned on making hajj this year will reap the same spiritual rewards as if they had gone.

For some groups, coronavirus restrictions have even come as a kind of boon. The Hajjah Project started in Los Angeles in 2016 to support local women who are making pilgrimage for the first time. In March, the group had to cancel a conference on how to plan for hajj. Instead, the project’s founder, Krishna Najieb, redirected efforts to developing a “Sisters Sunday Coffee” Zoom series where women discuss Islamic spirituality.

After the killing of George Floyd, she created another series called “Eight Days of Muslimah Prayer and Action.”

And instead of fundraising to help women offset the cost of pilgrimage, one of the group’s core activities, Najieb said the Hajjah Project used the funds to buy headscarves for incarcerated Muslim women.

“We had always felt like the Hajjah Project could evolve to not just supporting sisters making a first-time trip to hajj, but sisters trying to do things that are good for the community using Islamic values,” said Najieb, who performed hajj in 2015.

For Lachheb of Tayseer Seminary, he has also turned the absence of hajj this year into a spiritual opportunity. After the grief he initially felt, he said he has had time to reflect on the fact that closeness to God shouldn’t be tied to any physical place, and that, with the right intentions, he can still perform hajj internally.

“I have to find the Kaba of my heart, I have to find the Mecca of my heart,” he said.