Amanda Leduc is making a fairy tale out of her life. “It begins, as all fairy tales do, with a problem,” she writes in Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space. Leduc was born with cerebral palsy, which means her brain and legs don’t work quite as the world expects. Since her diagnosis at age three, her life has shifted between periods of joy and struggle. But unlike most fairy tales, her story strays from familiar tropes. There’s no easy moral lesson to be gleaned, no magical solution to her central challenge and no comfortable conclusion to her journey.

In Disfigured, Leduc blends memoir with cultural criticism and academic research to explore how fairy tales have shaped private and public perceptions of disability. As a writer and co-ordinator for Brampton’s Festival of Literary Diversity, Leduc knows that the stories we tell carry weight, especially the ones transmitted as part of our cultural heritage, inherited by each generation as they grow up. For her, fairy tales are among the “most quintessential of stories — the ones that we tell to make sense of ourselves and the world.” Disfigured reveals just how narrowly disability has been portrayed in these tales, and how that limits the possibilities available to disabled people in the real world, too.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

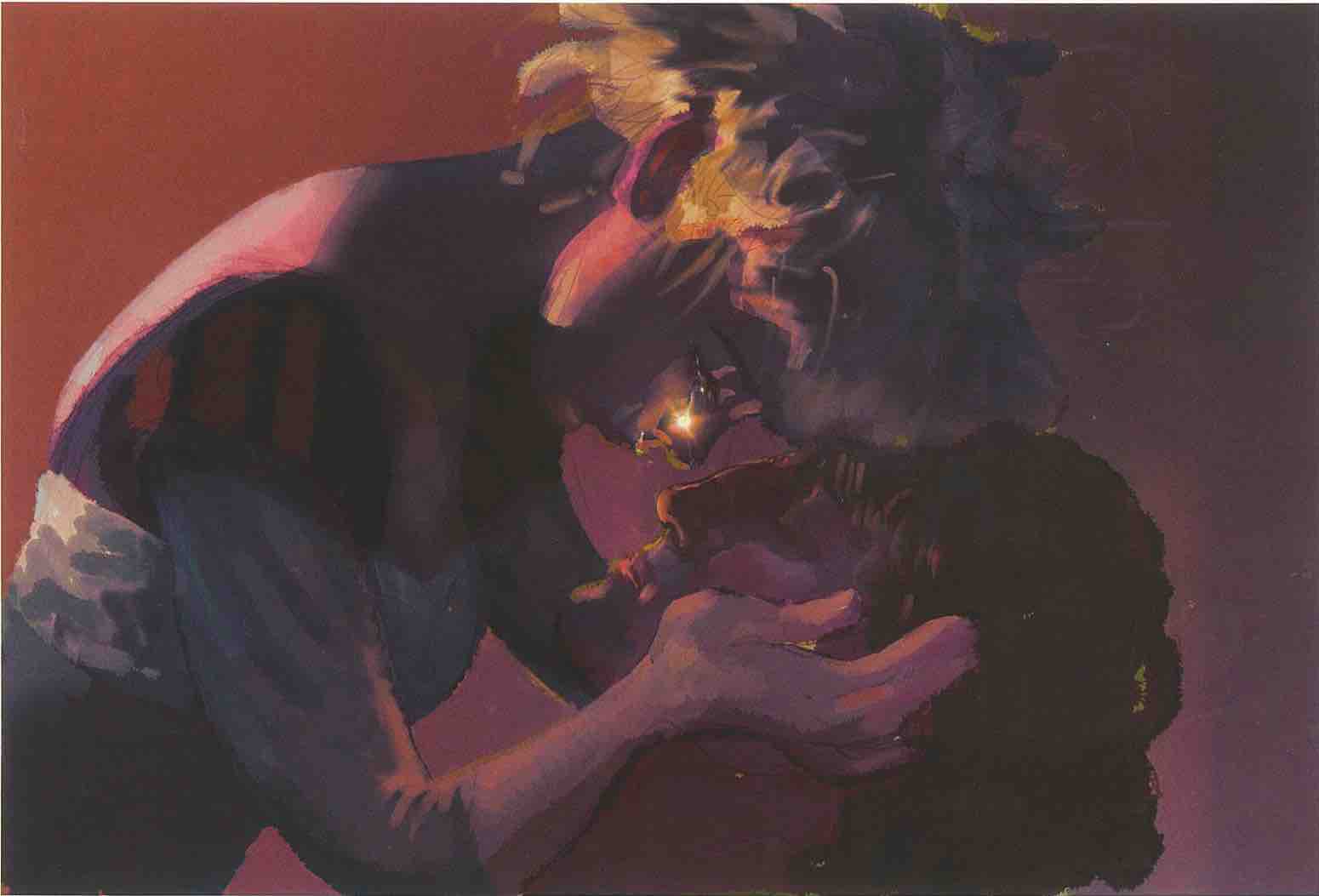

Historically, disabled characters in fairy tales have been objects to pity or fear. Disability has been used as a cautionary symbol — a metaphor for some moral imperfection that a character must overcome. In the original Rapunzel, the prince falls from the tower and is blinded by thorns, a punishment for being intimate with the princess before they’re married. He spends a period of time repenting in exile, his sight eventually restored by Rapunzel’s tears of forgiveness. Likewise, in Beauty and the Beast, the Beast is only “cured” of his bodily differences once he has proven his true virtue.

More on Broadview: Two Canadian disability advocates on righteous anger

If a character’s disability has not disappeared by the end of the story, they can often expect suffering or death. This is the fate reserved for evil witches or stepsisters, whose lasting conditions represent their irreversible wrongdoing. Bodily difference becomes shorthand for villainy. The stepsisters in Aschenputtel — the original and darker version of Cinderella — cut off their toes to fit into the glass slipper. They never grow back, and their eyes are eventually plucked out by doves. Hansel and Gretel’s blind and crutch-wielding witch gets pushed into a stove. The Lion King’s Scar, with his slashed face, is killed by hyenas.

Either as obstacles to overcome or punishments for evil, the representations of bodily difference in fairy tales reinforce an all-too-common understanding of disability, one that erases the complicated realities — and myriad possibilities — of disabled lives, Leduc writes. What’s more, these narratives insist that disabled people alone are responsible for accommodating their bodily difference, rather than society.

“We turn disability into a symbol because it has been socialized as not useful — a burden on society, an uncomfortable ending,” Leduc writes. “In a society that so often uses the disabled body as a symbol of some inner ill,” she asks, “how do we move forward and reclaim the messy, lived complexity of what it means to have a different body in the world?”

In Disfigured, Leduc pushes for systemic change. She envisions a world that recognizes our collective responsibility to meet the needs of all. In this world, there would be no need for magical healing or lifted curses or banishment to faraway lands. Instead, there would be accepted bodily differences, accessible ramps and normalized mobility aids. Inclusion would become a shared value and goal.

For Leduc, this shift begins with a conscious change in how we talk about and depict disability — especially in a literary scene rife with ableism. “The stories we tell must be different. It is no more and no less than that,” she writes. “To start telling different stories about a body that might look like mine, and reshaping the world to fit them.”

This review first appeared in Broadview‘s March 2020 issue with the title “Villains no more.” The print version of this article states that the Festival of Literary Diversity is in Hamilton; it actually takes place in Brampton, Ont.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.