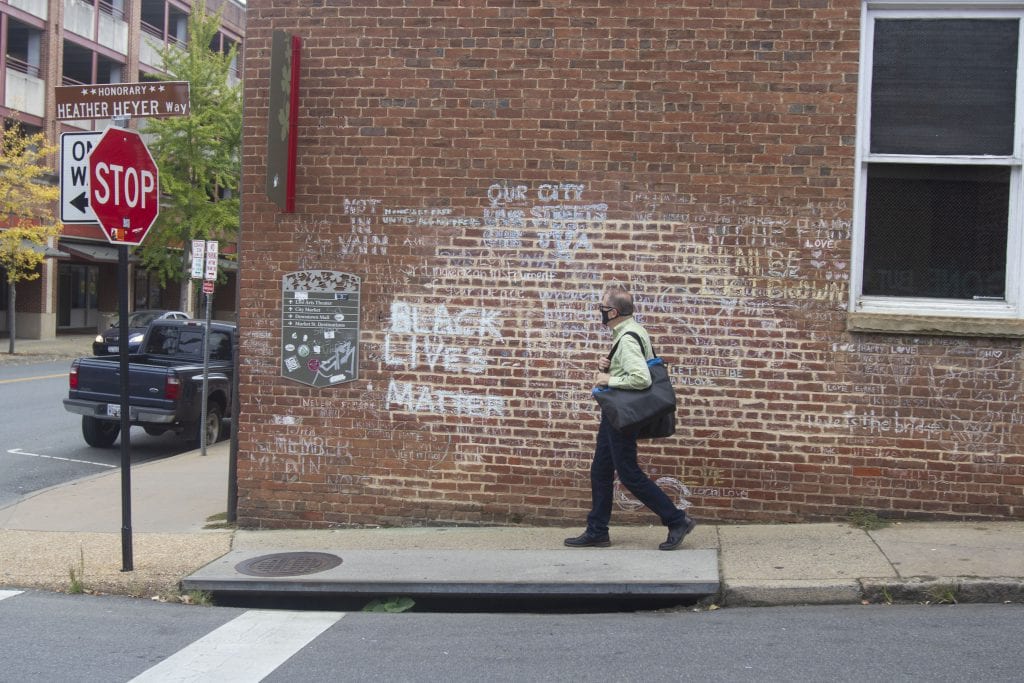

In August 2017, Charlottesville, a university town of 47,000 in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, became a catchword synonymous with the struggle against white supremacy. A campaign to remove statues of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson from public areas exploded into open warfare. Thirty-two-year-old Heather Heyer was killed. Two state police officers died when their surveillance helicopter crashed. TV transmission trucks ringed the courthouse and parks. “Charlottesville” was the name known throughout the world to indicate the war against white supremacy.

The initial salvo was fired in 2016 when an African-American high school student launched a campaign to remove the statues. Charlottesville city council responded by voting to remove the statues. White supremacists responded with lawsuits, successfully delaying the removal. This was followed by the Unite the Right rally in August 2017. Hundreds came from throughout the U.S. to join Charlottesville white supremacists. Many of them carried guns. They invaded Charlottesville, where they were met by hundreds of anti-supremacy demonstrators. Violence ensued, resulting in the death of Heyer and the two police officers. Scores of others were seriously injured.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

A series of court battles were launched by Unite the Right organizers. The basis of the defense’s case was that removing the statue violated state law. In January 2021, a new governor and state legislature changed the law to permit Charlottesville to remove the statues. However, numerous additional delays were built into the new law. Finally, on July 10, they were removed.

Below are quotes from three older African Americans, who are lifelong Charlottesville residents. They described growing up in the shadows of the statue of Robert E. Lee and their feelings about its removal. They spoke from the city with photographer Richard Lord.

James Hollins, 73, lifelong Charlottesville resident and retired railroad dining car steward: “When I was a kid we really didn’t know anything about the statue. Because I’m Black, I wasn’t permitted to go into the park. So, I could barely see the statue. I’d walk by the park and I wouldn’t pay any attention.”

“For me, there’s no symbolism to the statue.”

Frank Walker, 68, lifelong Charlottesville resident and retired technician: “Even as I grew and learned, I never considered the Civil War to be a war – it was a lost cause, an act of treason.”

“So, I looked at it with negativity. We never learned black history in school. The only mention of our past is slavery. What African Americans had done and accomplished you had to learn it on your own.”

Franklin Jackson, 81, lifelong Charlottesville resident, artist, and former Charlottesville police officer:

“I was the second Black police officer in Charlottesville. When I was a cop, Charlottesville was a country town. Now, with more people moving into the town, things changed. When I went on the police force, you could arrest a man for sitting on the sidewalk. It’s not that way today.”

IN summer travels along the Eat Coast we visited Charlottesville & were depressed by the poverty that for us dominated the city. Outside the city up on a plateau was the city of the rich white people. They did not pay taxes to Charlottesville. It was a very ugly reminder of the division & oppression. The schools & hospitals in the two areas reflected that division.