The idea of an origin had a romance to it before you were born. When I was your age, it was the easiest language I had with both of your grandparents. Stories about where they came from, and therefore stories about where I came from; a series of steps originating from two points on nearly opposite sides of the globe and landing in a little three-bedroom house at the edge of a brand-new suburban development west of Toronto. An explanation for our presence there, an unquestioned talisman. I was born somewhere else. Life there was good, but difficult. I came here, where life was good, but difficult in other ways. I worked hard. This place kept its promise to me.

Everyone among us has an origin story of some kind, though not everyone among us is encouraged to talk about it honestly as part of the social fabric of what we call Canada; an unspoken price of belonging to a place that relies on such stories in order to become real in a way that does not betray its own parasitic origins.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

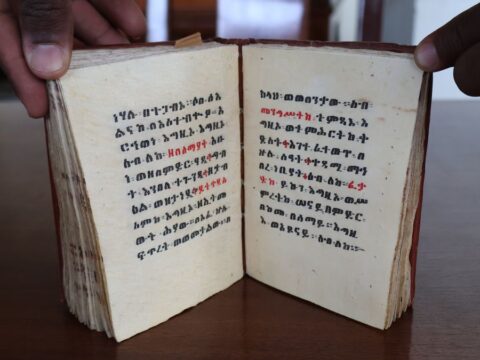

“Too much has been made of origins,” writes Dionne Brand in A Map To The Door of No Return. “All origins are arbitrary. This is not to say that they are not also nurturing, but they are essentially coercive and indifferent.”

A few years ago, I told you an offhand story about how your grandfather delivered Swiss Chalet meals as an evening job in his first years living in Toronto. It was the fourth lockdown of the pandemic, and when we ordered our Friday pizza treat, the courier would leave it in a sticker-sealed box at the foot of our door. When you finally saw Pa again, you asked him if he was still a “pizza man.”

I was not prepared for how much this would bother him. Not because he felt it in any way embarrassing or undignified, but because, despite telling me his own versions of origin stories for years, it was the first time he had been materially presented with the fact that such tellings could be relayed differently, understood in a way he did not expect—that they took on a life of their own after they were given. Specifically, it was the first time he had been presented with the fact that the stories he told could be passed down more than once, repurposed, the idea of beginnings diluted and debunked.

You were barely four at the time, and it’s unlikely that much of what either of us wanted to say would have stayed with you in the way we intended. I wanted to tell you a story that contextualized your family in the world around you as it was in the moment; he wanted it made clear that this part-time job was one step in a series of events that led to him meeting your grandmother, part of his own codified origins in a place called Canada. The world I was translating for you—your world—would shrink and expand wildly those first two years of the plague, in ways I hadn’t experienced as a child and, as a parent, constantly questioned how to navigate with care. One origin glossed in amber, another told out of fear. Instead, you heard these words, translated and once-removed; you thought, pizza! One story, told three times over, each of them a little true.

–

Coercive and indifferent. Is it coercive to talk to you about these things, to address you in this way? When I worry about this, I try to remember a sentiment repeated to me more than once when family and friends first met you: Wow, two days in labour? Just wait till you get to bring this up when they’re a teenager. Those hours I spent in bathtubs, on yoga balls, or keeled over in the shower are no longer memorable or particularly important to me. I tried, for a few months afterwards, to codify them in some way—to narrativize and attach meaning. I thought that the fact of birth itself, that those hours, marked the passage to motherhood. Weren’t they part of an origin story? Didn’t they mean something? What would you want to know about them someday?

I am not interested in using that anecdote as a parenting technique, ever; nor do I see it as a feat of strength these days. What I needed was medical intervention. I was up until that point too invested in the idea of an empowering birth—convinced that such a thing was guaranteed to those who knew what they were doing, convinced that such a thing was even possible when it came to giving birth for the first time—that I waited entirely too long to insist upon going to the hospital and getting an epidural.

I endured the pain because I was afraid of giving up control. That isn’t strength. I’ve learned and relearned that lesson often since, which I think gets closer at what a passage looks like.

What did I gain by waiting? I have trouble remembering so much about that labour, perhaps because an extended expectation like that removed my attention to detail. Sometimes this bothers me, and sometimes I think about the only two concrete things I know of the story of my own birth, repeated to me by your grandparents. From my mother: that I was born on a warm day, sunny, after twenty-four hours of labouring alone, walking through hospital wards where she heard other women shrieking. And from my father, when he calls to remind me each year: the minute I was born, Cutting Crew’s “(I Just) Died in Your Arms” was playing on the radio.

More on Broadview:

At one point, maybe hour twelve, the midwife recommended I rent a TENS machine that would rhythmically send electrical shocks through wires and stickers into my lower back to help me endure the pain. It’s easy to laugh about it now, this image of your father timidly pushing buttons on a stupid little black box in between bouts of me heaving what felt like gallons of yellow bile into the toilet. It felt horrible, trying to solve the problem of pain with more of the same.

What a way to enter the world, I thought. I had been working on a baby quilt for you throughout my entire pregnancy that I regretted not finishing. It took thirty-two hours for me to ask for the drugs; it would be another ten till I held you.

When I gave birth to your brother, I had exactly the birth I thought I wanted. I woke up to contractions, called the midwife, packed for the hospital, and was hooked up to painkillers within hours. I even put on a face mask while getting dressed. It wasn’t seamless: I bled everywhere, my arms wouldn’t keep a needle, and at one point the umbilical cord snapped at the root of the placenta with a sickening wet pop!, momentarily leaving the ephemeral organ lost inside me after birth. The midwife frantically used both hands to get it out. But compared to the endless hours, it was deliciously, frighteningly calm.

In experiencing the grace of that rare cooperation of the body, its environment, and a medical system that tries to mediate both, I came to believe that the first time, I had robbed myself of the agency I wanted by denying myself help for so long. I know now that both times I was looking for agency through two different versions of control.

Want to read more from Broadview? Consider subscribing to one of our newsletters.

The second time around, experience had taught me what I wanted and what to ask for. This is a type of power, no doubt. But knowledge cannot guarantee knowledge of the outcome, and it cannot always give you what you want. I wanted the story of a “good” birth. I’m no longer sure there is such a thing.

I have talked with you about being born before, but I saved this part. I want to be honest, because even though it may not touch you in your life the way it did me, it will always accompany you—the way death does, too. Birth can be beautiful, yes, but it can also be chaotic and impossible to categorize. There is no natural or unnatural, moral or immoral version of the experience, and so much harm stems from our attempts to impress these specific narratives on it. Birth can be beautiful, and often it is. But if not coercive, it, too, can be indifferent.

I understand now that the sacred parts, for me, began with an image: New Year’s Day, only it was evening by then. The midwife held you up in the hospital light, made syrupy by the drugs I’d finally taken. Your mouth open, a soundless howl of shock and surprise. I saw you before I heard you, and that image is with me still.

***

Excerpted from Story of Your Mother by Chantal Braganza. Copyright © 2025 Chantal Braganza. Published by Strange Light, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.