There were no announcements, no proclamations from church pulpits, no headlines marking the moment. But sometime over the past few years, the balance appears to have tipped: for the first time since Confederation, Christians no longer make up the majority.

Two surveys in 2023 — one by the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) and the other by the Non-Religion in a Complex Future Project — found Christian affiliation had slipped to 44 percent, down from 53 percent in the 2021 Statistics Canada census. Fresh ISSP data from spring 2025 places it even lower, at 42 percent.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

These stats are part of a global transformation that’s quietly reshaping the Western world and beyond. A Pew Research Center snapshot shows how just how far the shift away from Christianity has spread: between 2010 and 2020, Christians lost their majority status in Australia (falling from 67 to 47 percent), France (57 to 46 percent), the United Kingdom (62 to 49 percent) and Uruguay (61 to 44 percent).

“Canada now looks a lot like the U.K., Australia and France, where Christians have lost their majority, but the non-religious haven’t yet become the majority either,” says Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme, an associate professor of sociology and legal studies at the University of Waterloo.

She notes that a few solid surveys are typically enough to spot the trend, though results can vary slightly with methodology. The Statistics Canada census, for instance, can inflate Christian affiliation numbers because household heads often report teens as religious, even if they don’t identify that way. By contrast, the Non-Religion in a Complex Future survey (1,000 participants) and the ISSP survey’s sample (about 2,500), while also crafted to capture the wider population, surveyed people directly.

In Canada, she says the chief driver of the decline isn’t Donald Trump’s support among white evangelicals or sexual abuse scandals or any other headline-grabbing coverage — though, those often reinforce negative views among people already drifting from the pews. Instead, it’s slow-burn change.

Beginning in the 1960s, baby boomers stopped regular churchgoing, but kept the Christian label. Their children shed it altogether and each generation has since slipped further away — a trend echoed in Australia.

The retreat from Christianity takes different paths depending on the country. Britain and France’s withdrawal began in the 19th century, says Linda Woodhead, a professor of theology and religious studies at King’s College, London, while the shift has been more recent and rapid in Canada and Australia. Politics often lights the fuse: “It’s about how religion aligned itself with politics,” she says.

Nowhere is that clearer than in Quebec, where the break with Catholicism was spectacular. Pre-2020, three-quarters of Quebecers called themselves Catholic, even as most lived thoroughly secular lives. Then came the debates around Bill 21. “People began thinking, ‘I’m Quebecois. I’m laïc [secular] now, so I don’t have to be Catholic anymore,’” says Wilkins-Laflamme. In a remarkably short span, cultural identity was pried apart from Catholicism and reanchored in state secularism, sending Catholic affiliation into freefall.

Beneath these shifts lies another force: the secular state cannibalizing many of the church’s traditional functions, like social assistance, says Woodhead — a common feature of modern societies, alongside an expanding tapestry of religions.

In Australia, younger people have recoiled from conservative Christian positions on issues like climate change and sexuality, notes Douglas Ezzy, a sociologist with expertise in contemporary religion at the University of Tasmania. That pattern echoes Canada’s experience, where generational drift away from religion mingles with disillusionment over the Christian right’s moral stance.

“The question is, is this a Western thing that we’re exporting to other countries?” Wilkins-Laflamme asks. “It’s a globalized society now, so we’re all influencing each other.”

Early indicators suggest the trend is spreading, with Uruguay joining the ranks of Christian non-majority countries. Even in the Middle East, where reliable data is hard to come by because open professions of atheism can carry criminal penalties, hints of religious decline appear.

More on Broadview:

- A hitchhiker’s guide to the future of The United Church of Canada

- 5 reasons Canadians are leaving religion

- Canada is losing its churches. Can communities afford to let that happen?

For churchgoing Canadians, the decline is tangible — visible in echoing sanctuaries, hushed basements and hollowed-out parish halls. Immigration has long helped slow the slide in Canada, as many newcomers arrive from countries with higher rates of affiliation. But the picture is shifting. Overall numbers of permanent residents are expected to level off or dip slightly under the 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan. “I think Christianity still has some to lose,” says Wilkins-Laflamme, pointing out that so-called cultural Christians — those with tenuous connections to the faith — still abound.

Yet not all is decline. Orthodox Christianity, bolstered by Ukrainian refugees, is expanding in Canada, with new churches being built or shuttered ones reclaimed. Some Christian leaders, relieved from the burden of majority status, have discovered a bracing kind of freedom by adapting and even innovating. “They don’t have to worry about pleasing everyone anymore,” Wilkins-Laflamme observes.

But others are reluctant to admit that Christianity is now a minority phenomenon in society. “There’s still a lot of denialism,” she says.

This denial sometimes seizes on misleading statistics. Recent Pew data showing a slight uptick in religiosity among Gen Z in some countries was quickly interpreted by church leaders as evidence of revival. “Suddenly, I got a bunch of calls from media people saying church leaders in Britain are claiming there’s a revival,” Wilkins-Laflamme recalls. But she cautions that baseline levels remain “super low,” and the uptick likely reflects Gen Z still living with religious grandparents who are doing more childcare. The episode illustrates how religious leaders, searching for hope amid broader decline, can misinterpret statistical variations as signs of meaningful reversal.

The shift is seismic. Christianity once anchored Canadian identity, politics and moral authority. But that’s changed in this country, unlike in the United States where the Christian right still fuses religion with national identity. For a century, churches were Canada’s cultural backbone, the hub of politics, socializing, and social services. That structure has all but disappeared.

The loss brings consequences. Young Canadians today often encounter religion through fleeting digital snippets: “A 10-second YouTube clickbait, or an AI thing on how evil evangelicals are and how Trump is going to come get you,” Wilkins-Laflamme says with a laugh.

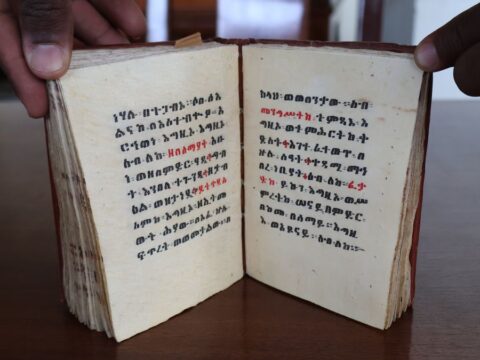

But what’s been lost is more than Sunday services, Woodhead argues. It’s two millennia of shared learning, art and vocabulary that even non-believers once drew on. The secular state cannot easily replace that. In a pluralistic democracy, it “can’t even provide a set of shared values.” That leaves a pressing question: what can take the place of a majority culture, now that the church no longer provides it?

The future remains unwritten. Current trends point to further decline, but shocks — from climate collapse to political upheaval — could reshape the religious landscape in unpredictable ways. “I’m still betting on the environmental crisis,” says Wilkins-Laflamme, suggesting it could force new forms of finding purpose and connection to become “socially normative.” But for now, a generation is groping for meaning beyond the sanctuary walls.

***

Julie McGonegal is a writer in Elora, Ont.

The writer correctly identifies many trends leading to Christianity becoming a minority demographic. Some of the problem comes from within the churches, however. One personal example: I have been a church musician for the past 42 years. There was a day when a qualified and experienced musician’s salary was comparable to that of public school teachers. Today it is frequently set to that of custodians. Memberships in the organist guilds has dropped by about half in the past 25 years and a majority remaining are now age 65 and above. The infusion of contemporary and rock music into churches has resulted in numerous organs being prematurely disposed of or kept around unused. Should we be surprised? I suspect similar trends are discernible among children’s and youth workers. I do not know how to turn these matters around.

So Christianity is based on how much we pay the organist? Perhaps you should join the ministerial union, I think they’re looking for a new contract.

Questions for clarification: How is majority being defined? And with what is Christianity being contrasted?

I’m clear that Christianity has fallen below 50% of the population but is it still the single biggest religious affiliation among the several categories? If so, it’s only lost majority contrasted with the broad alternative of non-Christian which seem a somewhat disingenuous characterization of majority status being lost. If one of the other several religious affiliations has overtaken Christianity as the single biggest affiliated group (including non-religious as an “affiliation” for these purposes) that would be more noteworthy and more accurately capture a loss of majority status.

As in geo politics, when there is a vacuum it can get filled with bad actors. (eg Libya and Taliban). Human needs for identity and community haven’t changed , but how its filled is changing rapidly from popularism to far right movements pitting us against each other. Values do matter and we have to be a place that is safe and provides an anchor to those values of love, compassion and empathy.