I first noticed the ascendency of “bubbles” as a buzzword several years ago. I am an architect and was attending a conference on green building. Speakers were concerned that some specialists worked in mental “bubbles,” ignoring their colleagues’ challenges, oblivious to the lack of connection between areas of work. And that could undermine the quality of the construction.

Since then, I have watched as “bubbles” teamed up with “silos,” “echo chambers” and other metaphors to spotlight something far more insidious: the walling-off of political subcultures that is taking place in many countries. It’s our new domestic isolationism.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

As an architect, Christian Scientist and lifelong student of worship spaces, I’ve thought a lot about walls and the interplay inside and outside of buildings, including sanctuaries. So I began my own interrogation. Are bubbles inherently bad?

Perhaps good bubbles have limits. Consider where we grow up. Hometowns are bubbles and usually benign. Home offers us years of endearing isolation from the wider world. It provides constants as we are nurtured, learn about life, our family and town, and reckon with becoming an adult. But there is a strong instinct, once adults, to learn first-hand how different people live and think. Some puncture the bubble and leave home. Others choose travels into trades or other bodies of knowledge.

Is this age-old ethic of curiosity and mixing with others aging out? Do we long for the cocoons we enjoyed as children? Even worse, are our minds becoming monocultures?

Judging by today’s political animosity and social media shouting matches, people are taking pride in mental seclusion. Our bubbles, originally a metaphor indicating something soft, flexible and light-hearted, have hardened into shells, steel-reinforced, opaque and rated for combat.

Professionally, I am used to working with the opaque and steel-reinforced. Architects use both to design privacy and longevity into buildings. And when I apply this logic about bubbles to sanctuaries, I feel that traditional religious spaces are, unfortunately, a perfect template for social introversion. Our sanctuaries are hardened shells.

Most modern buildings provide expansive views, porches and patios — interaction between the inside and the outside. But sanctuaries are, by tradition, disconnected from their public, social environment.

More on Broadview:

About 30 percent of adult Americans and nearly a quarter of Canadians — millions of people — regularly engage in religious activity, often in sanctuaries. Most come to get a sense of the divine. They may seek to understand how the world is set up and to participate in their community of believers. But don’t the hard-shell sanctuaries of tradition make it easier to ignore others as we contemplate the basic truths of existence?

Auditoriums and theatres are also disconnected. But they aren’t anti-social or detrimental because they seat us together to dramatize the outside world. By contrast, sanctuaries suggest a permanent separateness. They are isolation chambers. Inside we expect refuge. They are not a microcosm of society.

Our times compel us to assess the cost of this seclusion. I suspect it is greater than we imagine and paid for by public conflict. I suggest architectural transparency as one remedy. Let me tell you how I formed these opinions, and the singular church building that led me to them.

***

Sanctuaries are unique. Regardless of one’s religious interest, worship spaces have power over us. For thousands of years, they have moulded expectations and world views. Inside, sanctuaries, especially those with highly decorated interiors, model an ideal eternal world to which we aspire. Outside, most buildings are comparatively put-offish. Is there no sanctuary, new or old, that connects with outsiders?

Before I answer, picture this. Suppose we are sitting in a modest–sized traditional worship space. In front of us is a speaker or altar that provides focus, with an interesting background beyond. That focus, however, is enabled by the walls to our left and right. They make things private. They are interesting or boring, stone, painted drywall or glowing stained glass. Framed windows or upper clerestories might connect us to the sky.

Whatever the construction of those walls, the idea is that the world beyond them is to leave us alone. We are under the roof and world view of a religion. We invite the privacy it affords. Our presence is a consensual retreat from external reality.

For millennia, sanctuaries provided this alternate realm. One meaning of the word “sanctuary” is “a place set apart.” The intent is partly escapism (and historically, asylum) but also the assertion of holiness. Sanctuaries provide learning, safety, liturgy for some, a sanctioned narrative and social contact. We rub elbows with the like-minded. Across religions, places of meditation or worship help us affirm who we are as individuals and groups. After worship, we re-enter the world changed, like an artist experiencing art in a museum and returning to the studio.

Does purity of message demand architectural isolation? Not like we might think. We can open our space, our narrative, to a healthy awareness of fellow human beings.

In London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, the Crystal Palace proved glass can be a workable exterior shell material. Glass had been used in modern ways before, but the Crystal Palace had an all-glass exterior and was gargantuan. It caused an international stir. Architects became excited about transparency and made bold innovations with slender cast iron, glass enclosures and glazed roofs. About 70 years later, architects of the modern style dropped decorative cast-iron shapes in favour of clean steel lines. Broad spans of sheet glass opened the box for commercial and residential buildings. Life inside buildings was on display and became part of the social fabric. Those inside were more connected to their neighbourhoods.

Yet the hard-shell sanctuary remained unaffected. Worship spaces are seldom more transparent than in the past. After more than a century of glass buildings, very few sanctuaries visually connect to their immediate surroundings.

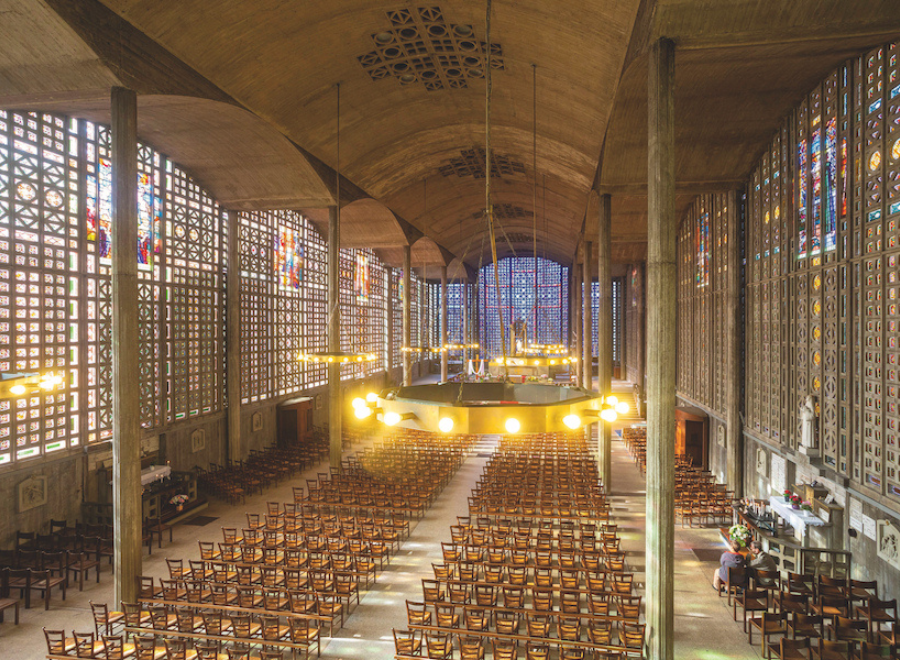

Most are chapels, and they only go so far. In 1923, on a main street near Paris, brothers Auguste and Gustave Perret built Notre-Dame du Raincy. Its walls are screens of coloured glass blocks. It is translucent, not transparent, but allows sounds of street life into the sanctuary. The walls are a modern translation of the stained glass that for centuries illuminated French churches. However, the glowing walls of Raincy offer no views of society beyond.

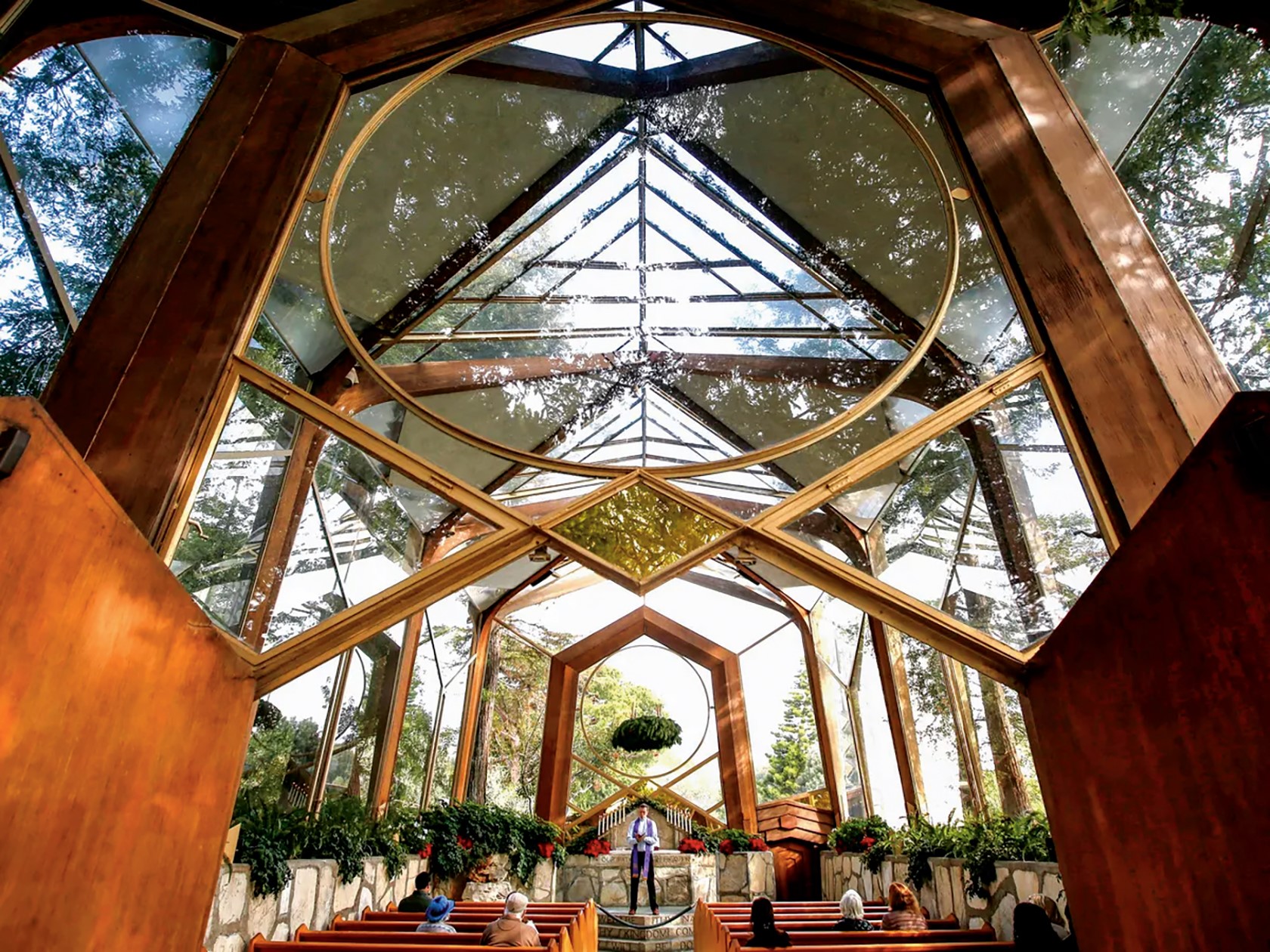

Wayfarers Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif., was designed by Lloyd Wright (son of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright) and has enveloped wedding guests in glass since 1951. Attendees could see sunsets over the Pacific Ocean, much like ancient Greeks saw the Aegean Sea from their temples on secluded rocky shores. The building site is under threat from landslides and the structure was recently taken apart for reassembly elsewhere.

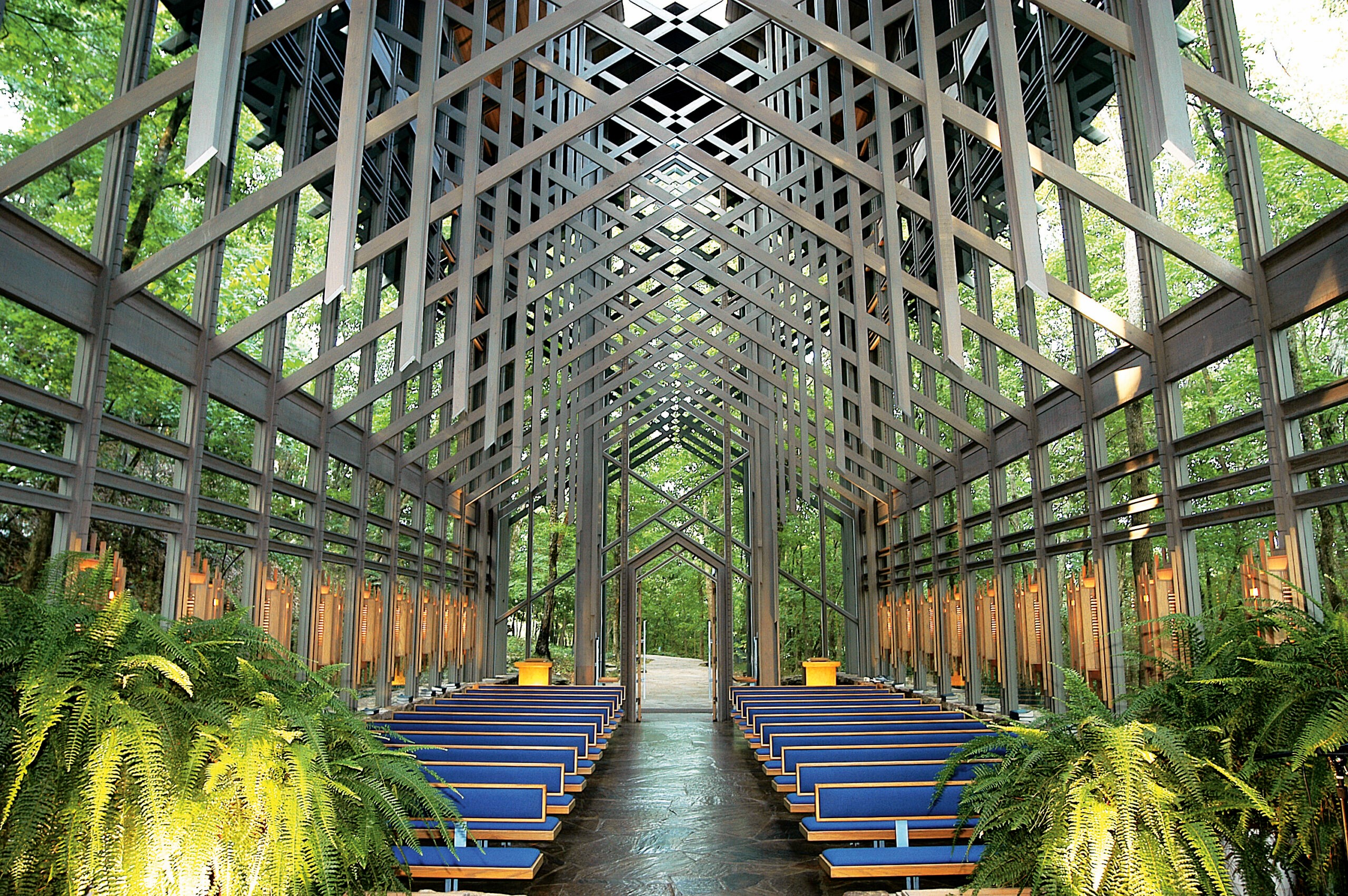

Thorncrown Chapel, built in 1980 in northwest Arkansas by architect E. Fay Jones, also represents a return to nature, with its forest setting and delicate vertical beauty. Philip Johnson’s gigantic Crystal Cathedral from the same year, now known as Christ Cathedral, is in the more populated setting of Garden Grove, Calif., but it is set amid parking lots and surrounded by landscaping.

Such structures dissolve the walls around worship. Inside, light creates an awareness of the outside. Yet these churches offer no visual engagement with a neighbouring public, no connection to a wider world of others. But a century ago, and just once, the idea of visually connecting a sanctuary to its surroundings was thoroughly tested. And to great acclaim.

It was in Berkeley, Calif., in 1910, about a decade before the sleek, glassy International Style of architecture came to North America. First Church of Christ, Scientist, Berkeley was the work of a congregation from a new denomination willing to experiment. They found an artistic architect with one foot in the past and one in the future: Bernard Maybeck.

Eulora Jennings, the first woman to graduate from Purdue University, led the church’s planning committee. A respected artist and metallurgist, she was captivated by Maybeck’s work and vision. Her committee recruited him aggressively. Maybeck signed on. Committee members regarded Maybeck’s stewardship to be God’s provision for their building. In turn, he was deeply moved by their intense faith and their confidence in him.

Maybeck was born in 1862 and reared in New York City. He attended a Berkeley Unitarian church with his wife. A graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he was heavily influenced by the churches of Europe and in particular Paris’s Saint–Germain-des-Prés. Maybeck proposed a sanctuary that was a play of weighty concrete and translucent glass, light and shadow, deep history and radical innovation. Half a century later, the building was said to have moved modernist architect Louis Kahn to tears.

Inside Maybeck’s concrete and wood design is a treasure chest of Byzantine, early Christian, Romanesque and Gothic motifs. Yet for the exterior walls, Maybeck convinced members to forgo the opaque treatment of traditional churches. Poof! The solid walls to the left and right vanish, replaced with steel frames of misty glass. From inside, you can see vague forms of people beyond walking, driving by. There is no separate outside sphere to be left behind.

At the time, the exterior was jolting. For centuries, only earthen materials like stone were considered suitable sheathing for churches. Here, length after length of prefabricated steel and glass walls are punctuated with wood posts and grand Gothic windows. These panels, known as factory sash, were new in the industry. The manufacturer considered Maybeck’s designs outlandish and initially refused to sell the panels to the church. But they allow a flood of soft light to reach the pews and worshippers inside. At night, passersby observe warm lights inside and hear bright organ music. Services are private yet revealing.

After the shock of the factory sash, First Berkeley’s architecture became a source of pride in the community. Christian Scientists still use the building today, but it’s also a destination for architects, historians and tourists from around the world. In 1977, it was designated a National Historic Landmark in the United States for its architectural significance.

The dynamic between inside and outside, however, still challenges us almost 115 years later. First Berkeley pokes holes in our instinct to isolate holy things. In a space drawing on thousands of years of Christian history, it erases historical divisions between believers and non-believers. It suggests a divinity that is not dualistic but ever-present.

Theologians might suggest that Jesus or others long ago dismissed such hard separations between the sacred and profane and between the saved and the unsaved. To me, First Berkeley suggests that transparency is a better fit with the Gospel’s spirit of divinity without borders.

Sitting in the church pews at First Berkeley in the early years at Dwight Way and Bowditch Street meant watching, hearing and feeling horses, carriages and people go by. Before long, it was Model Ts. Sitting in those same pews during a Sunday service today continues to be a connection to the outside world. In front are readers leading the service before a backdrop of Gothic tracery. To the left and right is a bright, misty live-action view of vegetation and life beyond.

We listen to ideas and stories from Bible lessons. We pray. We stand for hymns and sing or sit listening to vocalists. The ceiling is something to behold: Gothic motifs set in bulky kaleidoscopic wood trusses of dazzling craft and colour.

Together, these words, ideas, people, music, forms and colours hold the foreground of our thought.

Yet in the background of our thought is context, a living community. It is strange but subtle. Imagine sitting in the sparkling interior of Venice’s Basilica San Marco and hearing the music, ads and traffic reports of commercial radio faintly in the background. We may not focus on outside, yet we can’t fail to notice it.

The architectural vision of Jennings and Maybeck is one with the surrounding social fabric. The outside world is our world, teeming with life and an infinite variety of people and beliefs. It contains people and things we regard fondly or indifferently or with despair. Our awareness of the outside world mingles with the ideas of the readings. Do we then feel compassion and empathy with others beyond? Can architecture do that?

That is hard to say. But the design does ensure that we, literally, not lose sight of others. Whereas in a traditional church we might see apostles painted on the side walls, here we see our full-blooded neighbours go by. To the left: was that Paul? Possibly. Going to physics class, not Damascus. Congregants remain community members. Values contained in the readings can mix with, and even improve, our sense of community.

For Christians then, First Berkeley suggests that the divinity we associate with church extends in every direction to where people are. The space is horizontal. The trusses bearing down push our attention outward. There is no spacious heavenly dome, no playground above for our imaginations. Our world is one world, not two. Sanctuary is for communing, not escaping.

In one sense, Maybeck was responding to the impulse toward openness that infused the times and even the work of architects who were creating other types of structures. The Prairie Houses of Frank Lloyd Wright, like the Robie House in Chicago, completed in 1910, come to mind. But First Berkeley also reflects the broad-mindedness of Christian Science itself.

Christian Science’s leader was Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910), reared in a Congregational church. Her writings on prayer, for example, are an exercise in taking the self out of your perspective and treating others as you would choose to be treated. Her values are public-minded, as when she wrote that home “should be the center, though not the boundary, of the affections.”

She institutionalized that sentiment in one of the most prominent legacies of her church, the Christian Science Monitor. Unique in the history of church newspapers for high-level public affairs coverage, its mission is to “injure no man but to bless all mankind.” The publication still champions these inclusive values. In a June interview with the Monitor, author Michael Wear, founder of the Center for Christianity and Public Life, a non-partisan and non-profit religious institution based in Washington, D.C., advises readers to “go to politics in an others-centered way — in a way that centers the interests and well-being of the communities in which we live. And that opens up tremendous horizons.”

***

The tenor of public discourse today dramatizes the price we pay for seclusion and for walling ourselves off from the difficulties of others. In his much-quoted “stained-glass letter” from a jail in Birmingham, Ala., Martin Luther King Jr. wrote that, as he began his advocacy, he “felt we would be supported by the white church, felt that the white ministers, priests and rabbis of the South would be among our strongest allies. Instead, some have been outright opponents…and have remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained-glass windows.” King didn’t mean they were literally hiding behind church walls, but that they had retreated into mental sanctuaries and into zones of cultural comfort.

I contend that these mental hiding places are fashioned in part by physical worship spaces. Winston Churchill said: “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” Do walled-in spaces where we consider ultimate truths and seek disconnection also provide refuge to cultivate social inequities, hostility or just indifference toward others?

Does the modern monopoly of the hard-shell sanctuary come from our fear of others? Neglect of society beyond our circle? Our theology?

A sanctuary is a social as well as an architectural and religious construct. Builders of churches, synagogues and mosques should remember that according to Abrahamic tradition, the family we call humanity was born of a Creator who is, seven days a week — right now — in some way directly connected to everyone, everywhere.

Today, when religions make new buildings, they should — as Jennings and Maybeck did — experiment with transparency and proximity to the wider social world. Makers of glass have innovated for a century with the strength, acoustics, thermal properties, patterns and textures of clear and translucent glass. Today, glass holds artistic promise unavailable in Maybeck’s time, providing countless beautiful ways to reinforce openness and goodwill in our communities.

Let’s break the monopoly of the hard-shell sanctuary and see whether feeling a connection to everyone, everywhere can be part of our enjoyment of religious sanctuaries. What good might come from that?

***

William Marquand practises architecture in St. Louis and has degrees from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Yale University, where he studied under a joint arrangement with the school of architecture and the school of divinity’s Institute of Sacred Music. He is on the board of Friends of First Church, Berkeley, and is executive director emeritus of the Maybeck Foundation.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s December 2024 issue with the title “The glass sanctuary.”

As a person who is easily distracted, an open air concept would hinder my worship and prayer life.

Having been to the Crystal Cathedral prior to a rare rain storm in Anaheim, the congregation seemed more interested in how to get back to their cars dry, rather than listening to Schuller.

Edith Rankin Memorial United Church is another example, I could sit all day looking at the sail boats go by, rather than participate in the service.

As with the Notre Dame du Raincy, glass allows “outside noise”.

Our church is a block away from the local fire department and it seems every second Sunday there is an emergency. What little windows we have we can hear the call and the sirens enhance the morning prayers.

Finally, in a world where the “words are on the wall”, I have found most sanctuaries close the blinds during the service so the parishioners can read the songs up at the front. That defeats the purpose of windows.

Yes, looking at God’s beauty excites my Spiritual life, but it can also do the opposite.

Gary – thanks for your feedback. I wish I could say I’ve been to the Crystal Cathedral. One thing that makes Berkeley a bit different is that its glass is translucent and doesn’t provide that vivid realistic, detailed view of outside. It does tend to keep attention inward, for the most part. If you are interested, we will be talking about sanctuaries in Broadview’s National Online Reading Club Zoom meeting on Monday, Dec. 2. Anyone is welcome. Check out the Broadview site About > Reading Clubs. Hope to see you there. – Bill