Whenever there’s a large demonstration in Berlin, there’s a good chance it will pass through Kottbusser Tor. Known as “Kotti” to locals, it’s a major intersection in the centre of the city, where five streets meet at a wide traffic circle ringed by towering modernist social housing blocks.

At street level, there are bars and clubs, cafés, Turkish restaurants and supermarkets — including an outdoor market that’s open 24 hours a day — a hostel and a library. And on the southwest corner of the intersection, dwarfed by the grey graffiti-clad apartment building behind it, is a one-room, wooden shed-like structure built on a square of publicly owned land in the middle of the sidewalk, with windows that look out onto the busy intersection.

A lot of the protests in the past few years could be traced back to this small building. It’s called the “Gecekondu,” a Turkish word that literally means “placed overnight,” and which refers to structures erected quickly and without proper permissions. The first stage of the Gecekondu was indeed built overnight, following a neighbourhood street party organized in the spring of 2012 by Kotti & Co., an organization of tenants living in the apartments on the south side of Kottbusser Tor. The group had formed the year prior in response to rising rents that were pricing tenants out of the buildings. At first, the structure was simply fashioned out of wooden pallets to create a base and two walls, but later stages added a roof, doors and windows, building the Gecekondu into an enduring reminder of the community’s fight for affordable housing.

“It was kind of absurd, because this is social housing,” says Jannis Willim, an organizer with Kotti & Co., referring to the concrete apartment buildings, about 10 storeys high, a stone’s throw from where he sits inside the Gecekondu on a typically grey, early winter Berlin day. Despite the fact that these apartments are subsidized by the state, tenants who had been living in the buildings for decades soon found themselves struggling to pay rent, and the state organization meant to assist lower-income and unemployed people began instructing residents to find cheaper places to live.

The neighbourhood is at the centre of a city-wide battle between tenants and global real estate corporations. Since the 1990s, Berlin has been known for its cheap cost of living compared to other major metropolises. But in the past couple of decades, that’s also made the city an attractive place for international investors looking for a good return. Rising real estate prices in Berlin have outpaced every other German city in the past decade, as well as most other cities around the world.

In the decade after Kotti & Co. was founded, the median price per square metre in Berlin soared by nearly 190 percent, according to Guthmann Estate, a local real estate agency that caters to international clients. That’s an even greater jump than in Toronto, which has one of the hottest housing markets of Canada’s major cities, with prices rising about 110 percent in the same period, according to data from the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board.

Interested in more stories like this? Subscribe to Broadview’s weekly newsletter.

The upshot for Berlin’s renters is a very real and constant fear of displacement. According to Andrej Holm, a sociologist at Humboldt University of Berlin, about 25 percent of people who moved within the city in the past five years did so because they were displaced from their previous apartment by rising rents. Not only is this pushing people out of central areas and into the suburbs, but Holm says more and more people are being forced to find housing in smaller cities outside Berlin.

A similar story is playing out in major cities all over the world as corporate landlords take over the rental market. But in Berlin, where nearly 85 percent of people rent their homes, many tenants are not leaving without a fight. “The easiest way to stay in Berlin is to protect your actual conditions of tenancy,” says Holm. To do so, Berlin tenants are getting organized, taking to the streets and turning out at the ballot box to call on their city to take radical steps to address the housing crisis.

Closer to home, many Canadian cities continue to be counted among the least affordable cities in the world, while campaigns to freeze rents and prevent evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have forced housing into the headlines. It seems only a matter of time before the tactics employed by tenant organizers in Berlin start making their way across the Atlantic, too.

Not only is Kotti near the centre of Berlin, but it’s also the heart of a historically working-class and migrant neighbourhood that has been the site of immense change over the past few decades. When the hundreds of social housing units that surround Kottbusser Tor were built in the 1970s, the city was still divided. The Berlin Wall surrounded the area on three sides, making it an undesirable neighbourhood for most Germans. A large number of guest workers from Turkey moved in, and this has shaped the unique character of the district — and its struggles — to this day.

When those guest-worker contracts ended, many people used the money they’d earned to open shops, according to Willim, gesturing to the Turkish restaurants and supermarkets that can be found on nearly every corner around the Gecekondu. “Now there is a new wave of capital coming and people are investing in these houses, and you’re thrown out of your house,” he says.

“It has a lot to do with racism,” he adds. “People were invited to work and build up this area. Now that the job is done, nobody is lobbying for them.”

Willim grew up in the area and became involved in Kotti & Co.’s youth group shortly after the tenant initiative was founded. One of their first demands was to lower the cost of rent, but they didn’t stop there.

When Kotti & Co. built the Gecekondu, it was the beginning of a 10-year-long “occupation” of the public space at Kottbusser Tor, explains Willim. Initially, the structure was inhabited 24 hours a day, with people trading off shifts throughout the day and night. The goal was to make their presence — and their demands — known. The space has since become a nexus of housing activism in the city, hosting community consultations and meetings, and serving as a repository of information about the history of tenant organizing in the area.

Although Kotti & Co. is by no means the first tenants’ initiative in Berlin (the tenant movement here dates back to the late 19th century), it’s unique in the way that it has brought together people from all different backgrounds who were living in these buildings, and in how it has attempted to find new solutions to the city’s growing housing crisis.

When they were built nearly half a century ago, the apartments at the south side of Kotti were the property of a state-owned housing company. In 2004, the city sold that company, GSW, to a consortium of private investors led by Goldman Sachs and Cerberus — a decision that many in the housing movement cite as the beginning of Berlin’s modern housing woes. Nine years later, in 2013, GSW was bought out by Deutsche Wohnen, a stock-listed German property company that remains one of Berlin’s largest private landlords.

Now, after more than a decade of organizing, Kotti & Co. activists have won a small victory that they hope will protect residents from fluctuations in the private real estate market. Last September, the city announced it would be buying back their buildings from Deutsche Wohnen.

This announcement came just days before a landmark referendum in Berlin that itself was the result of three years of organizing by a campaign inspired in part by the bold demands of Kotti & Co. and other similar tenant initiatives. The campaign, called Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co., also wanted the state to buy back apartments (at below-market prices). However, instead of focusing on just a few buildings, organizers demanded that the state expropriate all private landlords that owned more than 3,000 units in the city, which would amount to approximately 250,000 apartments.

The expropriation campaign was a response to the emergence of the real estate corporation in Berlin, according to Joanna Kusiak, an urban sociologist at Cambridge University who lives in Berlin and was involved with the initiative.

Unlike typical landlords, whose clients are their tenants, the clients of real estate corporations are always their shareholders, explains Kusiak. “This means that, almost independently of the dynamic of the actual housing market, the managers of these corporations are obliged to try to raise the rent or to save maintenance costs, because their responsibilities are ultimately to their shareholders,” she says.

This process has been called the “financialization” of the housing market. Although this was initially an academic term describing the use of real estate as a commodity that could be bought and sold on the financial markets, the term has gained popularity in the last decade as a way to understand the international forces that are making it harder and harder for people in cities around the globe to find affordable places to live.

And there’s good reason for investors to be interested in housing. It’s become the largest commodity in the world, representing 60 percent of the value of all global assets, according to a report by Leilani Farha, who was the United Nations special rapporteur on housing from 2014 to 2020. Residential real estate comprises 75 percent of that number. Even more staggering, these figures — US$217 trillion in total — represent more than twice the world’s global GDP.

Farha has emerged as one of the faces of the fight against real estate financialization. The Ottawa-based lawyer is now the global director of The Shift, an organization that advocates for the right to housing in cities around the world. “I believe there’s a huge difference between housing as a commodity and gold as a commodity. Gold is not a human right; housing is,” Farha said in a 2019 documentary.

One of the landlords she has been particularly critical of is Akelius, a Swedish housing company that owns more than 44,000 apartments around the world — including over 14,000 in Berlin and thousands more in Toronto and Montreal.

Along with Deutsche Wohnen, Akelius has become a notorious name in Berlin’s rental market. Housing demonstrations in the city often include a group called Stop Akelius, formed in 2018 by tenants who wanted to draw attention to the behaviour of their landlord.

“When Akelius bought my house, I thought, okay, now I have to organize,” says one of the tenants behind the group, who wishes to remain anonymous due to a fear of reprisal from their landlord.

Common problems cited by Akelius tenants include a lack of heat and running water, poor communication from the landlord and frequent requests to raise the rent. “They are always trying to get as much from tenants as possible,” the resident says.

“Akelius’s business model, driven by the desire to maximise profits, has created a hostile environment for its tenants through a severe degradation of housing conditions, higher rents and increased risk or threat of eviction,” Farha wrote in a 2020 press release to the United Nations.

Akelius is on the radar of tenant organizers in Canada, too. The Stop Akelius organization has local chapters in Toronto and Montreal, and it’s one of a dozen private landlords identified by Keep Your Rent Toronto, an initiative formed in early 2020 to advocate for tenant rights during the COVID-19 pandemic. The group has called out the company for keeping more than 300 units empty at the beginning of the pandemic while the city was “deep in a housing and homelessness crisis.” According to Akelius’s 2019 annual report, the company owns about 3,500 apartments in Toronto.

It’s just one part of a greater trend toward corporate landlords in Canada. Writing last June in Policy Options, University of Waterloo urban planning assistant professor Martine August reported that Canada’s 25 largest financial landlords owned about 330,000 apartments in 2020 — “nearly 20 per cent of the country’s private, purpose-built stock of rental apartments.”

“I believe there’s a huge difference between housing as a commodity and gold as a commodity. Gold is not a human right; housing is.”

Leilani Farha, Former UN special rapporteur on housing

Tenants throughout Canada are beginning to organize in ways similar to tenants in Berlin, usually prompted by the same thing — the arrival of one of these new landlords. That’s how tenants of Golden Equity, another company profiled on the Keep Your Rent website, began organizing.

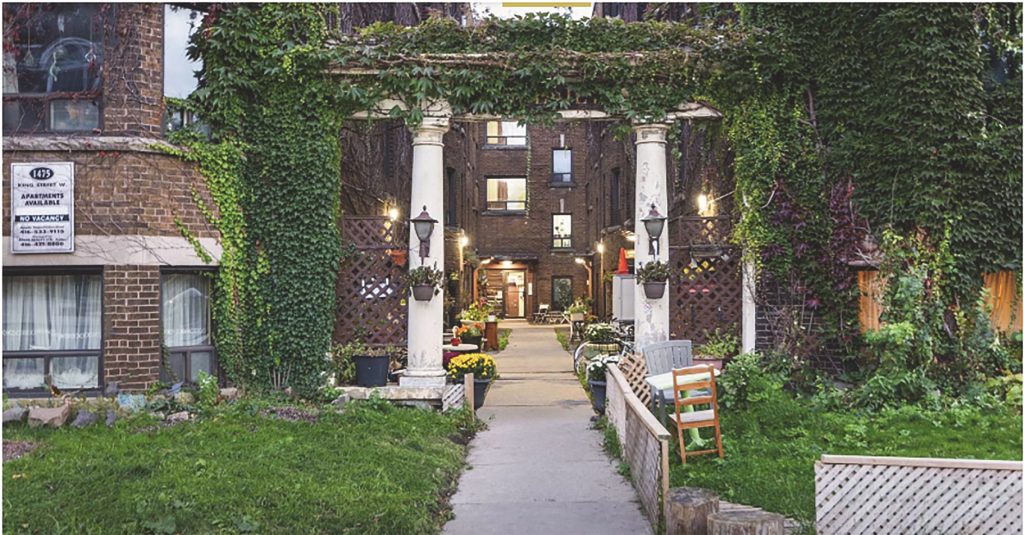

Previously, Emina Gamulin says her apartment building in Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood had been owned by what she calls a “mom and pop slumlord.” The building was generally maintained at an acceptable level, and tenants mostly didn’t complain. However, after Golden Equity acquired the property, Gamulin says that “things very quickly went into a state of disarray.”

Some of the first things renters noticed were superficial — the garbage was quickly piling up, and their beloved vines were cut off the building’s facade. Then, residents who had signed pre-authorized debit forms, which allow landlords to take rent directly from tenants’ bank accounts, began noticing mysterious withdrawals. Other tenants received unexplained eviction notices. In February 2021, a fire broke out in the boiler room, and there was a carbon monoxide leak after the new boiler was installed. According to Gamulin, the fire department blamed the fire on “routine maintenance deficiency,” and since then the heat in the building has only worked sporadically, even in sub-zero temperatures.

Gamulin and other residents quickly plugged in to the local tenant movement in Parkdale. “There’s already been so much messaging about when these new financialized landlords come in and their tactics that we all sort of intuitively knew we had to organize,” she says.

She has since connected with other Golden Equity tenants throughout the city and has realized that many of them have similar stories. “I think there’s a pattern of Golden Equity basically putting tenants in danger because of greed,” Gamulin says.

Golden Equity did not reply to a request for comment.

Inspired by Keep Your Rent and other similar initiatives, the tenants in Gamulin’s building have been participating in a rent strike. She says the strike started on April 1, 2020, shortly after the start of the pandemic, when about 60 percent of tenants in her building didn’t pay rent. Since then, it’s had its “ebbs and flows,” but she says it’s never completely ended, adding that more tenants joined the strike following the boiler room fire.

This kind of building-by-building activism is quickly becoming one of the most visible ways of tenant organizing — both in Canada and in Germany. All around Berlin, you see apartment blocks with banners draped from their balconies calling on the city to do something to address the housing crisis.

Sociologist Andrej Holm calls these apartment-based groups “micro collectives,” of which there are hundreds around Berlin. Many of them have websites, which they use to provide updates about their building, and nearly all use social media to connect with other tenant initiatives. “You can buy real estate and buildings in every part of the world as a more-or-less secret economic transaction,” he says. “But in Berlin, if you buy a house, the next day you will have a Twitter account connected to it, you have some banners on the building and you have this group of tenants writing letters to the politicians.”

Some of the banners specifically mention Vorkaufsrecht, which is known in English as the “right of first refusal,” a process by which the state can intervene to prevent the sale of a building to an exploitative landlord.

One of Berlin’s biggest champions of this model is Florian Schmidt, a councillor in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, the district where Kottbusser Tor is located. If a private individual or company wants to buy a building in an area where social protections exist, they need to communicate with the district, which then has three months to decide if it wants to intervene in the sale. The state may opt to purchase the building instead, or the interested buyer may sign a contract with the district that prevents them from taking actions that could increase the rent or force people out of the building, such as luxury renovations. “It’s a kind of protection for the people who live there,” Schmidt says.

Over the past four years, Schmidt says his district has intervened in the purchase of about 2,500 apartments. Around 700 of those were bought by the state, while another 1,800 were sold to the initial buyer, who signed a contract promising to protect the building. About 30 percent of apartments in his district are now owned by non-commercialized landlords.

His goal is to protect half the housing stock from the commercial real estate market, though a recent court ruling that limits districts’ right of first refusal may hamper that plan. “The city should be a place where you can live without fear,” he says. “Infrastructure like water or electricity or traffic or housing should not be a market-driven system.”

Many Berliners agree with Schmidt. On Sept. 26, when city residents were asked whether the state should socialize a quarter of a million apartments owned by Deutsche Wohnen and other major private landlords, about 56 percent voted in favour. With more than one million “yes” votes cast, it was the most successful referendum in the city’s history.

Gamulin has been following from Toronto the advances made by the housing movement in Berlin, and while she calls the referendum “exciting,” she has some reservations. She’s not convinced that using democratic or legal mechanisms such as referendums or expropriation would work in Canada.

She says one of the big questions of tenant organizing is whether it is worth it to go through the proper legal channels when met with a bad landlord. “The majority of times the answer is no — it’s actually stacked against us,” she says. Instead, Gamulin thinks rent strikes and other actions that go “straight to the source” can have better immediate results for renters.

But even in Berlin, the recent tenant victories are only cautiously celebratory occasions for housing organizers. While the city’s purchase of the buildings at Kottbusser Tor has removed the apartments from the commercial market, this doesn’t automatically preserve their social housing status. The social housing contracts for most of the Kotti & Co. buildings are still set to expire in the coming decade — with some apartments aging out of these contracts before the end of next year.

The goal of Kotti & Co. was never solely to have the buildings resocialized, explains Willim. Instead, the group wants tenants to have a more democratic say in how their buildings are managed. “This will not come from anywhere,” he says. “We will have to organize for it.”

If there are not further changes made to keep rents affordable in the neighbourhood, tenants there may still find themselves outpriced.

Likewise, the overwhelming support for expropriation in the September 2021 referendum indicates that housing organizers are making inroads with the general population. On the other hand, the vote was not legally binding, and Berlin’s current mayor is skeptical of expropriation.

“I worry that if people aren’t prepared to back it up outside of the electoral system, the dream will die,” Gamulin says. “I hope people are prepared to keep fighting, even if their government is not supportive of their goals.”

For now, the Gecekondu still stands on the southwest corner of Kottbusser Tor as a reminder of the tenants who are fighting for their ability to stay in the buildings above.

***

Isaac Würmann is a Canadian writer based in Berlin.

We hope you found this Broadview article engaging.

Our team is working hard to bring you more independent, award-winning journalism. But Broadview is a nonprofit and these are tough times for magazines. Please consider supporting our work. There are a number of ways to do so:

- Subscribe to our magazine and you’ll receive intelligent, timely stories and perspectives delivered to your home 8 times a year.

- Donate to our Friends Fund.

- Give the gift of Broadview to someone special in your life and make a difference!

Thank you for being such wonderful readers.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

Comments