When I was a child, hell was as real for me as chocolate.

I remember sitting in the back of my family’s Peugeot pickup truck, watching rust-coloured dust from the road swirl around me, trying to decide which would be worse: going to the dentist or going to hell. I knew about dentists from a cassette tape of twangy children’s songs that promoted Christian virtues like patience and self-control. One song warned of the painful cavities that awaited children who ate candy, drank pop and refused to brush their teeth. I shunned candy and brushed my teeth religiously. One Easter, my aunt gave me a chocolate bunny, a solid ingot, sweet as sin and heavy as the Old Testament. I held it in its box and cried until my cousin took it off my hands and ate it in front of me.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

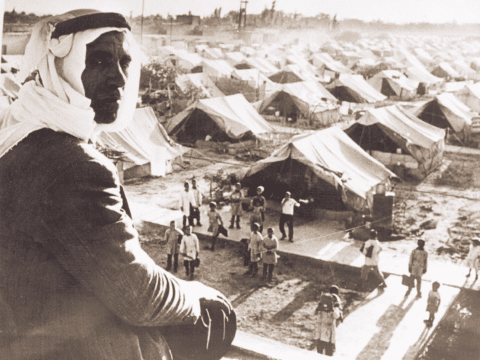

Hell loomed just as large as the dentist. I grew up in Burkina Faso, a small African country of dusty grasslands wedged between the deserts of Mali and the rainforests of Côte d’Ivoire where my evangelical Mennonite parents had moved to be missionaries. Our neighbours practised a loose version of Islam mixed with traditional West African spirituality. Every time we heard of a death in the village — a child who fell from a palm tree, an elder claimed by malaria — I knew we had lost another soul to hell.

Salvation, I was told, was a simple choice. Either you acknowledged your inherent sinfulness and asked Jesus to forgive you, or you didn’t. Either you jumped from the burning building or you suffered the consequences. I knew that hell wasn’t literally on fire. The flames were a metaphor for suffering. I pictured a grim wasteland bathed in utter loneliness, stripped of every pleasure, populated by people I knew.

One of my friends in the village was a boy named Yaku. He had a dimpled smile and one lazy eye. He could weave a fedora from palm leaves or fashion a toy truck from bicycle spokes. He’d dropped out of the village school to work his father’s fields, and he and I communicated using the few French words we had in common and a lot of hand gestures. Yaku showed me how to catch catfish and trap bush rats, and I taught him to play UNO. We never talked about Jesus. My village friends observed the rules of their religion and expected me to be faithful to mine. They mouthed an Islamic benediction when they sat down to eat and chided me if I neglected to say a Christian one before digging in.

Secretly, I felt guilty for not doing more to warn my friends about their impending doom. I prayed nightly for their conversion and salvation, penciling names onto scraps of paper I tucked between the pages of my Bible. How could God fail to answer this prayer? He wanted this as much as I did, didn’t he? Yet all around the world, people died daily without being saved. I couldn’t understand how a God who purportedly loved humanity enough to sacrifice his own son for them had failed to devise a system with a better success rate.

The answer I was given by my parents and other church leaders was “free will.” Mass casualties were the price of allowing people the freedom to choose. God only wanted followers who chose him of their own volition, so he had tied his own hands. As bizarre as it may sound, there’s a logic to the doctrine of free will and damnation that provides an answer to theism’s age-old question: Why is there suffering in the world if God is all-loving and all-powerful?

By the time I was in grade school, I’d gotten over my early fear of ending up in hell. I’d asked Jesus into my heart (several times, to be safe) and knew that his forgiveness reached retroactively into my past and forward into my future. In theory, it was possible to lose your salvation, but only by committing the gravest of sins: denying Christ. Obviously, I would never do that. If someone had told me that one day I would lose my Christian faith — and that hell would be the cause — I would not have believed them.

More on Broadview: Former fundamentalists describe the trauma of leaving their faith

More than half of Americans believe in a hell, a place “where people who have led bad lives and die without being sorry are eternally punished,” and 41 percent of Canadians — more than the percentage who regularly attend church — believe in the existence of a punitive afterlife. Hell may be “the most powerful and persuasive construct of the human imagination in the Western tradition,” Scott G. Bruce posits in The Penguin Book of Hell, a recently released compendium of historical writings about the bad place.

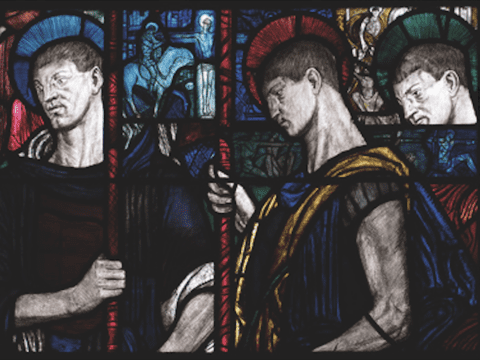

Hell has occupied a central place in Western cosmology for thousands of years. The Christian hell has its roots in mythologies that go back to well before the birth of Christ. Ancient Greeks believed in an underworld called Hades that was not strictly a place of punishment, though it contained an abyss called Tartarus where unrepentant souls suffered eternally for serious crimes and temporarily for lesser ones. Later, the wildly popular Roman poet Virgil, writing a few decades before the birth of Jesus, drew on Greek mythology when he described the torments of the shadowy underworld awaiting fraudsters, murderers and traitors. And the Hebrew scriptures that Jesus would have grown up reading spoke of sheol, a dim and dusty afterlife similar to the one found in early Mesopotamian lore, a place that swallowed everyone without discrimination.

The word translated frequently as “hell” in the Gospels comes from the Greek word gehenna, a valley near Jerusalem where Israelites had once sacrificed children to the Canaanite god Molech. Gehenna doesn’t appear in the Gospel of John. When Jesus mentions it in the other three Gospels, he seems to wield it as a rhetorical device that represents absolute wickedness. Cut off your offending hand lest it drag you into gehenna, he warns. “Sons of gehenna” he calls the religious elite who exploit the poor. In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus tells a series of parables that culminate in dramatic judgments in which the righteous receive eternal life and the undeserving are burned up or cut to pieces or cast into “outer darkness.” In Mark and Luke, many of these same stories appear without the dire, moralistic endings. What’s unclear from the Gospels is whether Jesus saw hell as a real posthumous destination or a provocative figure of speech.

The Christian doctrine of hell as we know it took shape in the centuries after Jesus’ death. Early sects quarrelled over the nature of hell. Was the purpose purification, retribution or deterrence? Were the punishments eternal or temporary? One leader named Origen felt that eternal punishment for a mere lifetime of sin was overkill and proposed a hell similar to Tartarus — a place where souls were purified until they could eventually be reunited with God. Even Satan was ultimately reformed, Origen argued.

Two centuries later, in the early AD 400s, St. Augustine would shape the doctrine that humans were hell-bound from conception and only Christian faith could save them. In The City of God, Augustine used rumours of a fire-dwelling salamander and his own experiment with a slice of cooked peacock meat to argue that human flesh could burn for all eternity without being consumed.

At the Synod of Constantinople in AD 543, Christian bishops declared that hell was eternal and anyone who suggested otherwise would find themselves excommunicated. Origen was sentenced posthumously to an eternity of pain. Christianity had transformed the dreary, undiscriminating afterlife of antiquity into an eternal holocaust for all but a righteous minority. Life on Earth would become a great exam, a contest which only a few would win.

The doctrine would continue to inspire a fearful faith in God and would even play a role in the formation of the United States of America. Twelve hundred years after hell was rubber-stamped at Constantinople, a New England preacher named Jonathan Edwards described hell in such blood-curdling detail that the sobs and shrieks of his listeners forced him to cut short his sermon. The Great Awakening, an American religious revival led by Edwards and other preachers in the decades before the American Revolution, unleashed a tide of emotion and encouraged ideas of nationalism and individual rights that helped fuel the fight for independence. And the waves of religious revivals that followed caused the new republic’s proportion of evangelicals to double by 1850 — to three million people. My own parents grew up on the Canadian Prairies not far from the United States border in a Mennonite subculture heavily influenced by an American revivalism that emphasized hell and personal salvation.

Early sects quarrelled over the nature of hell. Was the purpose purification, retribution or deterrence? Were the punishments eternal or temporary?

There was another person whose soul I worried about just as much as Yaku’s. My uncle Jerry Fast lived in Canada, had a sandy-blond ponytail and drove a square-snouted Peterbilt, a truck whose aesthetic beauty he defended against all other models and makes. Jerry celebrated the absurd. He quoted Kurt Vonnegut and liked to confound his nieces and nephews with impossible questions: “What’s the difference between a duck? Is it farther to Winnipeg than by bus?” If you sneezed, instead of saying “Bless you,” he quipped, “Nothing happens when you die.”

I loved Jerry. He too had grown up as a missionary kid and knew what it meant to live with a foot in two cultures. Whenever my family came home to Canada on furlough, Jerry would invite me down to his place in the country, make a fire in the backyard, crack a beer and ask me what I was thinking about. I knew Jerry was an atheist. He’d started out a devout and serious child (not unlike me), and had gone to seminary intending to be a pastor. Then something had happened. I wasn’t sure whether stone-faced Mennonite pastors had chased him from the church, or if he’d simply ventured too far into the perilous realms of liberation theology and textual criticism. He never tried to dissuade me from my beliefs, but he did explain how the biblical texts came together over the centuries — mistranslated, redacted, rubber-stamped and debated by church authorities, each with their own political agendas.

I tried to save him. When I was 15, he invited me along on an 18-hour trucking trip to deliver a load of hogs from Winnipeg to Sioux Falls, S.D. This was my chance. As we hurtled south on the interstate I mustered every argument I could to bring him back from the brink. Jerry graciously parried every thrust of my teenage logic. Eventually, I gave up. Someone would have to rescue him, but it wouldn’t be me. I added Jerry’s name to my nightly prayers.

At age 19, I moved back to Canada to go to university. I earned a journalism degree, got married, and found a job copy editing and reporting for an evangelical newspaper whose columnists railed against abortion, gay marriage and the dilution of Christian orthodoxy. Meanwhile, my partner and I were living in Winnipeg’s North End, a low-income neighbourhood estranged from the rest of the city by a wasteland of railroad tracks and centuries of racism. We were trying to start a church for the poor and disenfranchised. Every Sunday, we made coffee, set out chairs in a drop-in centre and prayed someone would wander in off the streets.

But the binaries of my childhood were not holding. At a community event, I heard an Indigenous elder tell his story and realized that this man’s spirituality was far deeper than mine. Yet he wasn’t a Christian. How could this be? I read the diaries of Etty Hillesum, a Jewish woman in her 20s who lived in Amsterdam during the Nazi occupation and died in a concentration camp. Her writing was erotic, tragic, transcendent. Her encounter with the divine was as real as mine. I listened to Leonard Cohen, a mystic who fashioned profane and thrilling poetry from the religious symbols of my childhood: “When they said ‘repent,’ I wonder what they meant.” Were all these people really going to hell?

Doctrinal debates broke out in the newspaper’s lunch room. One day, the topic was hell. I don’t remember much about it except a cheerful comment from our accountant, a woman in her 50s who usually stuck to topics like snowmobiles and soccer. “I don’t believe in hell,” she said offhandedly.

“Why not?” I wanted to know.

She shrugged. “I’m a mother. I’d never send any of my children to hell. Not for any reason. So why would God?”

I couldn’t think of a more convincing theological argument for the non-existence of hell. And I haven’t since.

That winter I got an email with bad news. My friend Yaku had died. Feeling ill, he’d stayed home from his work in the fields and had died alone in his bedroom. He was 35. I’d been planning to mail him a deck of UNO cards as a reminder of our childhood friendship. After I read the email, I poured myself a glass of wine and stared out my apartment window at yellow street lights glaring on dirty snow and listened to the weeping hiss of the radiator. I knew with absolute certainty that Yaku was not in hell. In fact, I realized I hadn’t believed in hell for a long time. I’d just been afraid to admit it. Unbelief is a terrifying thing to accept, especially when it’s the one thing that can endanger your immortal soul. In the 1600s, French mathematician Blaise Pascal formulated his famous philosophical argument for belief in God: if reason cannot prove or disprove God’s existence, it’s safer to believe in a God who may not exist, than to disbelieve and risk damnation. I formulated my own version of Pascal’s wager: If there was no hell, I was free to believe what I liked. If there was, I wanted nothing to do with a God who sent people there.

Not long afterwards, my uncle called me at work and invited me over to his sauna. That night we sat in a cedar shack in the middle of a poplar grove hushed by snow and passed a flask of Jack Daniel’s. I told my uncle I didn’t believe in hell anymore.

He didn’t laugh at me for taking this long to figure it out, only nodded his head and said: “You know, I think there’s a bigger gap between people who believe in hell and people who don’t than between people who believe in God and people who don’t.” Then we stepped outside into the lung-biting cold and scrubbed our arms and shoulders with handfuls of needle-sharp snow. I felt my mind expand to encompass the whole of the breathing forest around us. I looked up at the hole between the treetops and the wheeling stars above and I knew that there was nothing to fear.

Evangelical Christians have good reason to cling to their views of hell. Mainline denominations with vague or non-existent doctrines of hell are in decline, while evangelical Christianity is not.

Growing up, I’d been warned about versions of Christianity that didn’t subscribe to a belief in a literal hell. They were cotton-candy Christianity, popular and sweet but lacking substance, even dangerous. If there were no consequences for sin, there could be no morality. Without the possibility of damnation, Christ’s sacrifice was moot. “We cannot repudiate Hell without altogether repudiating Christ,” wrote English novelist and theologian Dorothy Sayers. Hell was Christ’s righteous judgment on sin. “One cannot get rid of it,” she wrote, “without tearing the New Testament to tatters.”

Hell has had its abolitionists. Eighteenth-century Christian thinkers like James Relly, John Murray, Elhanan Winchester and Jane Leade came to believe that all people would be saved. They were labelled “universalists,” a word uttered then, as now, with disdain by conservative Christians. Eventually, the universalist church became a Christian denomination in its own right.

Evangelical Christianity still zealously guards its teaching on hell. The late Canadian theologian Clark Pinnock was excoriated for expressing doubts that a God of love would torture people eternally for the sins of a finite life. Carlton Pearson, a rising star in the Pentecostal church, was declared a heretic and lost his congregation after he questioned the orthodoxy of eternal punishment. And the popular pastor Rob Bell left his mega-church congregation and touched off a furor that landed his story on the cover of Time magazine when he dared to suggest that Gandhi was in heaven. “Farewell Rob Bell,” tweeted author John Piper.

Evangelical Christians have good reason to cling to their views of hell. Mainline denominations with vague or non-existent doctrines of hell are in decline, while evangelical Christianity is not. Whether hell is the cause would be hard to prove. But Christians who worry that extinguishing hell will endanger the faith have a legitimate fear. Once I stopped believing in hell, my other convictions fell like dominoes. Hell had stood as a boundary between me and the world of ideas. Fear doesn’t loom large in my memory; I was simply careful. Imagine growing up in a nice house surrounded by a fence. Beyond the fence you can see forests, rivers, mountains and plains. But everything outside of the fence is contaminated by invisible radioactive waste. You have what you need inside. You’ve never ventured out, and you don’t want to. The risk is too great. Then one day you discover that the story you grew up with is false. There’s no radioactivity. You’re free to explore. Imagine the thrill.

Suddenly, everything I believed was up for grabs. Maybe Jesus wasn’t God, just some long-haired Palestinian peasant with revolutionary ideas. Maybe God was more like the oxygen we all breathed than a benevolent father. I didn’t really need to decide. I could let the questions hang. My salvation was no longer at stake.

For some weeks after my belief in hell dissolved, I walked the streets of Winnipeg in a state of wonderment. The world had been transformed by a glittering cloak of fresh snow. I felt like a butterfly freshly hatched from its chrysalis. I stared into the faces of people I passed on the sidewalk and knew that they were neither saved nor damned, just human beings like me wandering in this beautiful and tragic world.

I quit my job at the Christian newspaper.

Eventually I fell in with another kind of Christian — humanists with a spiritual bent, people who read the Bible as an archetypal human story, who acknowledged many paths to enlightenment, who saw Jesus more as a mystic revolutionary murdered by an empire than a cosmic sacrifice or a lifeline to heaven. Hell was not a destination or a judgment, but a metaphor for the suffering humans inflicted on each other and themselves.

I’m drawn to this story, yet I can’t help but think that my uncle was right, that such hellfire-free expressions of Christianity are closer to his open atheism than the do-or-die religion in which I was raised. I’ve come to see hell as the hook on which the whole edifice of my childhood belief system hung. Now, in my own mental shorthand, I draw a line between religion and spirituality. Religion includes hell, spirituality does not. Religion is about citizenship, about who’s in and who’s out, and the rewards and punishments that follow. Spirituality is a search, a posture, a direction, but never a passport.

I know, of course, that many people consider themselves Christian and don’t believe in hell. I’m fine with that. But I can’t do it. To do so would would betray the intensity of my childhood faith.

When I was in the throes of my existential crisis, when I knew I couldn’t go on believing but feared what would happen to me if I stopped, I read a novel by Marilynne Robinson. In Home, a prodigal son comes home after 20 years of estrangement to visit his dying father, a Presbyterian minister. Jack is damned, and he knows it. As a youth he fathered a child with a girl from a poor family. After Jack fled town, the child died. The girl’s family despised both Jack and his family. The minister was disgraced. Throughout the story, Jack, his sister and his father circle each other warily, alternately inflicting love and heartbreak.

The book broke me open. Robinson imbues each of her damaged characters with so much humanity and handles them with so much tenderness and grace that it’s possible to believe that love can exist without its binary, hate, and that there could be a God somewhere incapable of vengeance. Reading the book, I wept. I wept for Jack, so utterly persuaded of his own damnation, and for his father who wanted so desperately to forgive him, yet feared that God would not.

When I finished the book, I gave it to my mother. I didn’t tell her why. I couldn’t muster the courage to say that I was Jack. I’ve abandoned the truths she holds as close to her heart as the children she birthed. To ask her to relinquish her belief in hell would mean asking her to tear out the burning heart of her faith. There’s nothing left for us to do but to try to love each other across that unbridgeable chasm.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s November 2019 issue with the title “What the hell?”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Josiah Neufeld, thank you for baring your soul. “I stared into the faces of people I passed on the sidewalk and knew that they were neither saved nor damned, just human beings like me wandering in this beautiful and tragic world.” This, I believe, is the wisdom and truth of the Sacred Spirit, the Mystery of goodness within us that works to help us see family in each other the whole world over.

There is a movie put called Hell and Mr. Fudge, as well as a book similar. It is about a Church of Christ minister who was challenged on the popular Hell theory. He ended up finding it was not Biblical, the wicked perish (John 3:16). The wages of sin is not everlasting life in hell, but rather the wages of sin is death etc etc

Mr. Neufeld what is your theological interpretation on Jesus’s own teaching and comments on hell and by extension the existence of the devil? I think he is the subject matter authority on both. It seems would be folly to the Christian community (wherever it lies along the theological spectrum) to preach your article as authoritative. Which begs the real issue here that this magazine never engages. By whose authority does the Christian community live? (personal experience only). Here is some personal experience that the editors of this magazine did not publish when I commented on your article a few days ago. You would be interested to know that there are United Church ministers who have conducted deliverance of people and places from evil spirits. I know two. The Observer, the forerunner to this magazine carried at least one such story. Would you call these ministers less authoritative than your own? And the United Church of Canada Book of Worship (1984) has liturgical material for the deliverance of people and homes of evil spirit. As Shakespeare said, “There are more things in heaven and earth, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

“The flames were a metaphor for suffering. I pictured a grim wasteland bathed in utter loneliness, stripped of every pleasure, populated by people I knew.” This thought is true, Hell in Scripture is the antithesis of Heaven. (2 Thessalonians 1:5-9) “[8-9]He will punish those who do not know God and do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. And these will pay the penalty of eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His power.” This passage and others show that hell is the absence of God. Think of EVERYTHING we have here on earth created by God, it won’t be found in Hell. Your rejection of God will be approved, He will grant your wish. (For me the scary thing is verse 8b – and do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus) This tells me God will be judging on His Holy terms, not by what we think should happen.

“Secretly, I felt guilty for not doing more to warn my friends about their impending doom. I prayed nightly for their conversion and salvation, penciling names onto scraps of paper I tucked between the pages of my Bible. How could God fail to answer this prayer?”

My friend we’ve all been there (I have a son who has been a constant prayer to this day), God tells us to plant the seed, and He will make it grow. We cannot save people; we can only show them the way. They have to make the decision, not God or us (that’s why it’s called free will).

“I couldn’t understand how a God who purportedly loved humanity enough to sacrifice his own son for them had failed to devise a system with a better success rate.” I can’t believe He loved and cared for me enough to kill His Son when He didn’t deserve it. But now when I approach God (through a wonderful plan) God will see Jesus and His Holiness and not my filthy doings. Do you not think God loves His perfect creation enough to see everyone go to Heaven? (I Timothy 2:4)

“The Christian hell has its roots in mythologies that go back to well before the birth of Christ.” This at least proves humanity came from a single race, most mythologies believe in a Heaven, at least one God, and morality – I wonder where that came from? It is trying to acknowledge who God is on a human level. (The created knowing the Creator)

“And the Hebrew scriptures that Jesus would have grown up reading spoke of sheol” Actually, most Hebrews were not sure of an afterlife as well, there was a lot of tension between the Pharisees and the Sadducees about this topic. Once Christ died and rose again it was certainly clarified.

“She shrugged. “I’m a mother. I’d never send any of my children to hell. Not for any reason. So why would God?”I couldn’t think of a more convincing theological argument for the non-existence of hell. And I haven’t since.” Again you miss the gospel’s point. We are not SENT to Hell, we choose to go there.

My final comment is the same when people say “you can believe what you want”….. If I’m wrong, I look a fool but won’t care. But if I am right, you have a lot to lose. Hell is real and it is Eternal. (At least in how I understand my Bible)

Repeating Christian doctrines doesn’t make them true

I am surprised at the comments below arguing that Hell is essential to Christian belief-the author of the piece plainly agrees with them, which is the entire point of the article.

For my part, I am one of those Christians who does not believe in an eternal Hell-I take Origin’s view, that Hell is a place of purification and repentance through which we all get to pass-similar to what the Roman Catholic Church has come to ‘purgatory’, I cannot see how a just God would punish people eternally for temporal sins, nor how a God of Love would permit those loved to remain forever unreconciled, nor how an all-powerful God would sacrifice Himself for anything less than the salvation of all creation. It does not make any sense to me.

The RC’s do not teach there is no Hell. You might check out Bishop Robert Barron’s website comments on hell. He has a huge audience including many Protestants.

Your thoughts, I agree, I don’t like it either, but remember God is who He is.

On our wedding day, my wife’s aunt gave us a beautiful mounted painting of an eagle soaring, the detail of the feathers, you could almost touch. When she gave it to us she said: “Uncle ‘Fred’ spent four months on this, and threw it in the garbage” That picture has been hung a predominate place in three homes for over 35 years.

God is the painter. Sin is the flaw the artist sees in the picture. (No one else may see that flaw) Only the painter has the right to toss the painting, does He not? Do you think the painting has the right to disagree?

I am actually stunned by this account. I truly didn’t see how there could possibly be anyone out there who is walking the path I have walked (am walking) in so many ways. Of course, some big differences (I’m a 79-year-old woman now married to my long-time love, Annie), but…. Brought up in a loving Mennonite home in Pennsylvania, married, divorced, and always afraid and questioning the concept of hell. It’s too long a tale to even attempt here (I’m sure anyone reading this is breathing a sigh of relief), but how incredibly grateful I am that Josiah shared his story, the closest to mine I’ve ever read. Thank you, my brother. Peace.

Love is right; hate is wrong – except! It is wildly presumptuous to quote God (especially word for word), but it is equally foolish to refuse to follow what you believe is God’s truth. It is important to follow what one finds to be right; it is equally important to change if one finds the first choice is wrong. It’s valuable to see the honesty of truth that looks different. Life will never be easy!

“The word translated frequently as ‘hell’ in the Gospels comes from the Greek word gehenna, a valley near Jerusalem where Israelites had once sacrificed children to the Canaanite god Molech.”

1. Gehenna is not a Greek word originally, but Aramaic and Hebrew. Given that the word is at the core of the article’s topic, not a trivial error.

2. The “Israelites”, which I suppose refers to the Children of Israel, i.e. Jews, did not sacrifice to Moloch. The whole thing is ironically referenced in Psalm 121 (“Unto The Hills”). Pagans did and there is archeological evidence for this. Not a trivial calumny.

3. Jesus as “Palestinian peasant”, a passing comment in the article, can’t be ignored. It’s a reference to Replacement Theology. Not trivial.

Adding 1, 2 and 3 suggests a distasteful agenda.

J.

There are the early church teachers. Men who were directly discipled by the apostles who then discipled other teachers. These men wrote that the soul was immortal and that punishment was eternal. Did the apostles get it wrong?

Could God really deny salvation to someone just because they re unconvinced by the historical basis for the resurrection? Could someone really be condemned to hell for not being able to reconcile the idea of a loving God with a world of pain? What about people who sincerely see no need for the role of God in creation?

Wow, I attended the Defenders conference at Village Church in Dyer a few years ago. It was excellent. I’m finding it hard to believe this is the same conference. I believe hell is real and a literal place. If you have ever had the horrific experience of an encounter with the devil you would know this. It is disheartening and a sign of the times that this conference would promote these viewpoints. Your advertising for the conference is in very, very poor taste in my opinion. Sorry.

I, too, have been questioning the ECT view of hell for a long time though I still believe in Christ. I appreciate you sharing your story.