Pope Francis was known to be a keen saint-maker, having canonized 942 new saints during his papacy — far surpassing his predecessors Benedict XVI and John Paul II, who canonized 45 and 482 saints respectively. One of his last official acts before he died was to advance the causes of several candidates for sainthood.

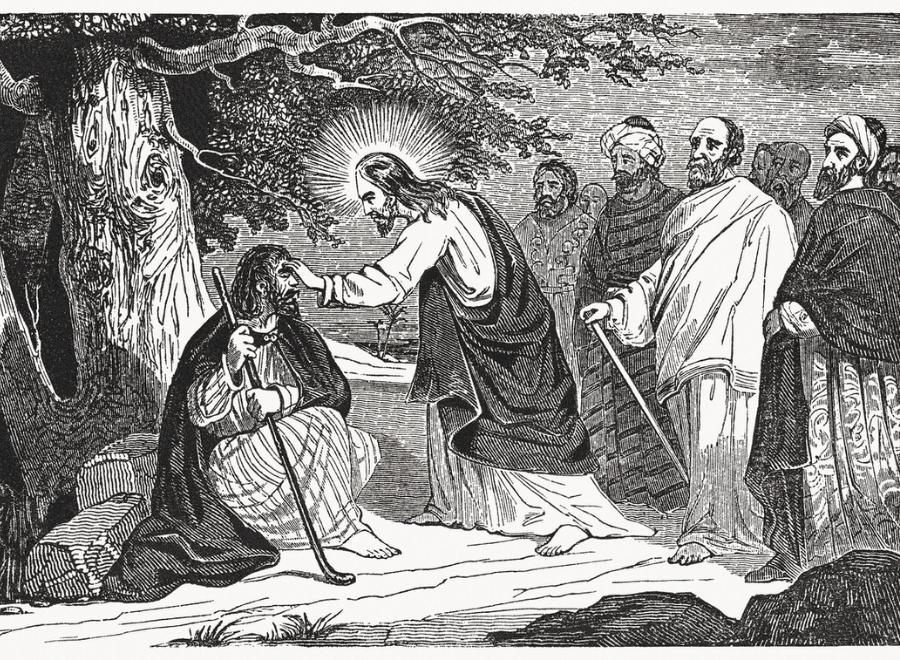

In order to become a Catholic saint, a candidate has to have two intercessory miracles that are officially recognized by the Church (an intercessory miracle is one that comes about after the person’s death, when the living pray for them to intercede with God on their or someone else’s behalf). While miracles can come in all shapes and sizes, most of the modern saint-making miracles are medical in nature: everything from inexplicable recoveries from injuries to cures for diseases that defy scientific explanation.

For many people, the idea of miraculous cures — especially in the 21st century — is little more than superstitious nonsense. But for Jacalyn Duffin, a hematologist, medical historian, and professor emerita at Queen’s University, the idea of miracles isn’t incompatible with the world of modern medicine. In fact, she sees the two things locked into a kind of symbiosis, with one constantly informing the other.

More on Broadview:

Duffin is uniquely positioned when it comes to the field of medicine and miracles because her work helped confirm the second miracle that led to the canonization of the first Canadian-born saint, Marguerite d’Youville.

Back in 1987, Duffin was struggling to find employment after moving to Ottawa for her husband’s work. She managed to befriend several doctors in the hematology department at Ottawa General Hospital and one of them, Dr. Jeanne Drouin, offered her a one-off job giving an “independent expert opinion” on slides of bone marrow. The only caveat was that she wasn’t allowed to know anything about the case — she was simply to write her report and collect her fee.

It didn’t take long for Duffin to realize that these were no ordinary slides. They showed an initial case of acute myelogenous leukemia, treatment with chemotherapy, a remission, then a relapse followed by more treatment, and finally, a second remission. The outcome was an impossible one in the 1970s, when a relapse of the disease was considered incurable. She figured that the slides, combined with the secrecy surrounding the case, meant that she was doing an assessment for some kind of medical malpractice suit. She said as much to Drouin when she handed over her report.

“Or,” said Duffin, somewhat cheekily, “are we dealing with a miracle?”

In fact, they were. Duffin was later asked to appear before an ecclesiastical tribunal in order to recount how the patient — whose family and community had prayed to Marguerite d’Youville — had experienced a recovery that couldn’t be explained by medical science.

Want to read more from Broadview? Consider subscribing to one of our newsletters.

At first, Duffin was reluctant. She was an atheist who was married to a Jewish man and didn’t feel comfortable testifying that a miracle had taken place. But the nuns working on d’Youville’s cause seemed delighted by these facts. To them, it meant that she had no vested interest in the outcome of d’Youville’s sainthood and could therefore offer an objective opinion.

“I was totally blown away,” Duffin says. “Being a historian, I thought, how can the church be so held hostage to medical science?”

The experience — which culminated in Duffin being invited to d’Youville’s canonization ceremony in Rome, where she met the late Pope John Paul II — set her on a new path. She would go on to study the history of medicine, miracles and the Catholic Church, eventually publishing two books on the subject. Through this work, she has come up with some fascinating theories.

At the heart of her work is a seemingly simple question: What, exactly, is a miracle? For Duffin, it’s a “happy event that is scientifically unexplained.” She notes that when religious people talk about miracles, they’re referring to events brought about by God, but for herself, she doesn’t assign agency.

But the history of miracles is also the history of science. In her book Medical Miracles, Duffin explains that during the Counter-Reformation, Prospero Lambertini (who would later become Pope Benedict XIV) revolutionized the church’s process for deciding who could be canonized as a saint. In an effort to ward off Protestant charges of Catholic superstition and corruption, Lambertini introduced a process that required potential miracles to be proven scientifically inexplicable before they could be accepted.

“Each time a new technology comes along, it only takes a very short time for that technology to show up in a miracle file,” says Duffin. “The Vatican wanted the unexplained event to defy the most up to date science possible … You can track the history of all those technologies through the miracle files.”

Though saint-making miracles vary based on time and place, Duffin found that the majority of the post Counter-Reformation miracles that appeared in the Vatican Secret Archives were medical in nature — not unlike the ones that led to the canonization of Marguerite d’Youville. She believes this trend exists because unexplained healings are among the few types of miracles that can be verified by a third party—typically a doctor—who has no stake in the candidate’s cause for sainthood.

But while medicine may have a role in creating saints, Duffin believes that saints can also play a role in medicine. In her other book, Medical Saints: Cosmas and Damian in a Postmodern World, Duffin argues that saints offer emotional hope where medicine often cannot. What she means is that, even in the most dire cases, when all the information at the physician’s disposal says that the patient is unlikely to survive, saints can provide a bulwark against despair for the patient and their family.

Duffin’s work ultimately points to a deeper question: where do we look when science runs out of solutions? For some people, of course, the answer is nowhere, but others might turn to some kind of spiritual force: a god, their ancestors, or even a Catholic saint. That latter group might be looking for comfort, but they might also be looking for something more. And Duffin would be the first to tell you that sometimes miracles really can happen — though, she’ll also hasten to add that just because something is a miracle, it doesn’t necessarily mean it has a divine provenance.

It could just be that the explanation has yet to be discovered.

***

Anne Thériault is a journalist in Kingston, Ont.

Thanks for reading!

Did you know Broadview is the only media organization in Canada dedicated to covering progressive Christian news and views?

We are also a registered charity and rely on subscriptions and tax-deductible donations to keep our trustworthy, independent and award-winning journalism alive.

Please help us continue to share stories that open minds, inspire meaningful action and foster a world of compassion. Don’t wait. We can’t do it without you.

Here are some ways you can support us:

Thank you so very much for your generous support! Together, we can make a difference.

Jocelyn Bell, Editor/Publisher, CEO and Trisha Elliott, Executive Director

Comments