Fiery rhetoric from Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s colourful president, may grab the occasional headline, but the deeper story over the past decade is that Latin Americans have been busy reinventing politics.

Since 1998, a variety of left, centre and populist parties have won elections in at least eight countries from Argentina to Nicaragua. These governments have in common their promise to end the free-market economic policies — what Latin Americans call “neo-liberalism”— imposed after a series of military takeovers in the 1970s.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Today, instead of administering power on behalf of corporate elites, the new leaders draw policy cues from the region’s growing social movements. Even where such changes have not yet happened (Mexico, Colombia, Peru, most of Central America and parts of the Caribbean), major opposition parties emphasize goals such as education, health care, land reform and ecological protection.

Across the region, the political and economic changes are the outcome of intensive work by grassroots groups. In 25 years of writing from and about Latin America and the Caribbean for readers in North America — and since 2000, working on behalf of The United Church of Canada with its partners in the region — I have watched the construction from the ground up of scores of organizations that today are transforming the political landscape and working for change.

These small groups knit themselves together into social movements and alliances that eventually transcended national borders. Realizing that protests against abuse were not enough to produce change, they met in spaces such as the World Social Forum and Hemispheric Social Alliance and began to propose policy alternatives that smart politicians adopted.

The groups have their origin in a quest for alternatives that began a half-century ago. Decades of “developmentalism” — what Latin Americans called the mixed economic strategies in which governments played a role in designing industrial policy and nurturing a national capitalist class — had brought improvements, but the poor majority was largely excluded from the benefits.

As the Cold War deepened, and particularly after the 1959 triumph of the Cuban Revolution, repression across the region increased: progressive governments were overthrown (often with U.S. complicity, as in Chile in 1973), and revolts in Central America in the 1980s were crushed.

Community leaders concentrated on efforts to strengthen ordinary people: the creation of literacy programs, co-operatives and credit unions, or the struggles around specific issues, such as land reform, access to water or the defence of human rights. They trusted that, provided with basic education and some experience of social organizations, people would eventually choose options that addressed them and their needs — when the time was right.

I REMEMBER A CONVERSATION I had in 1983 with a 40-year-old Haitian man named Jacob. He lived in a small city north of Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic and made his living by weaving baskets in an artisans’ co-operative. But his real work was teaching Haitian migrant workers how to read and write.

In those days, there were about 500,000 Haitians in the Dominican Republic. Most of them were sugar cane cutters, some accompanied by their families; others, like Jacob, were political exiles who fled the father-and-son dictatorships of François and Jean-Claude Duvalier. Sharing language skills was a way to help the Haitian exiles understand how the Duvalier regime used power, and to see what could be done to change things.

“The reason Duvalier has not yet been defeated,” Jacob told me,” is the lack of awareness among people inside the country and those who have left.” He said people did not realize that their poverty could be defeated. “We’re offering class consciousness and awareness that the dictatorship can be overcome.”

Jacob then described the popular education method of adult literacy developed by Paulo Freire in Brazil in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The approach spread quickly across Latin America and to parts of Africa and Asia.

In roughly the same period, Christian churches began to advance concepts such as the “preferential option for the poor” and pastoral strategies that placed the poor at the centre, not at the margins.

Across the region, small Christian communities, usually linked to a larger parish, proliferated. Like the literacy circles, these base communities emphasized consciousness raising and participation. At first, this was largely a Roman Catholic phenomenon, but many Protestants (whose churches had tended to focus on the urban middle class) shifted their mission priorities.

New ways of working with the poor brought pastors into new situations: accompanying land takeovers by homeless people on the edges of Santiago, Chile, or creating co-operatives and credit unions in the Dominican Republic. As theologians such as Peru’s Gustavo Gutiérrez reflected on their experiences, the struggle to overcome poverty became the starting point for theologies of liberation.

Practitioners of popular education and proponents of liberation theology played a big part in the revolutionary movements in Central America in the 1980s, a time when many Canadian Christians first became aware of the currents of change in Latin America. But fierce opposition from the U.S. government led to the defeat of the Sandinista revolutionaries in Nicaragua’s 1990 election, and to the entrenchment of conservative parties in power in Guatemala and El Salvador.

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and with increased corporate power in larger countries such as Brazil, Mexico and Argentina, there was little political space for advancing the interests of the poor except through slow, grassroots processes — and the international solidarity campaigns that accompanied them, such as the Jubilee petitions for debt cancellation.

By the end of the 1990s, however, there were signs that neo-liberalism had run its course. Notwithstanding the bold promises of the politicians — Mexican President Carlos Salinas famously assured his people that they would join the “first world” when Mexico joined Canada and the United States in a free trade agreement in 1994 — economic growth stagnated during the neo-liberal years. Earlier, between 1960 and 1980, the region’s per capita gross domestic product grew by 82 percent and living standards improved. But from 1980 to 2000, with the advent of neo-liberal measures such as privatization and free trade, per capita GDP increased by only nine per cent.

On the face of it, Venezuela seems like an unlikely starting point for a progressive resurgence. For more than 30 years, two parties presided over an oil-enriched economy and took turns in power. But in 1998, a former army colonel named Hugo Chávez rode a wave of discontent with corruption and skepticism about the traditional parties and won the presidency with 56 percent of the vote.

Since then, socialists or social democrats have been elected to head Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia and Ecuador. In Nicaragua, the Sandinistas — blander now than in the 1980s — returned to power in 2007. And social movements in Guatemala are allowing themselves a small measure of hope with the recent election of Álvaro Colom, the first move toward social democratic government in the country since the 1950s.

Among the new leaders, Chávez is one of a few who say they are working toward socialism. Most have pragmatically concentrated on breaking past dependence on financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund; and some have revived aspects of developmentalism — reasserting the state role in economic development after years of neglect.

Bolivia is the one country about which it can truly be said that the social movements themselves are in power, and their backbone is the Indigenous peoples’ movements. But the Bolivian government is also the most at risk of violent overthrow: the opposition has shown no restraint in its effort to undermine or remove President Evo Morales.

Two successive Socialist presidents of Chile, in power since 2000, are sometimes included among the progressives. But their elections were supported by multi-party coalitions, and their power is restricted by deals made during the years of military dictatorship. Chileans still press for more profound change.

One of the landmark achievements of Chávez was the 2007 creation of the “Bank of the South.” This new development bank — unlike the Inter-American Development Bank or the World Bank — is run by Latin American governments and not controlled from the north.

Some partners of The United Church of Canada are deeply engaged in strengthening social movements. The Ecumenical Centre for Service and Popular Education in Brazil and the Ecumenical Research Department in Costa Rica train community and church leaders for involvement in social movements. The Latin American Popular Communication Centre in Colombia focuses on grassroots efforts such as community radio.

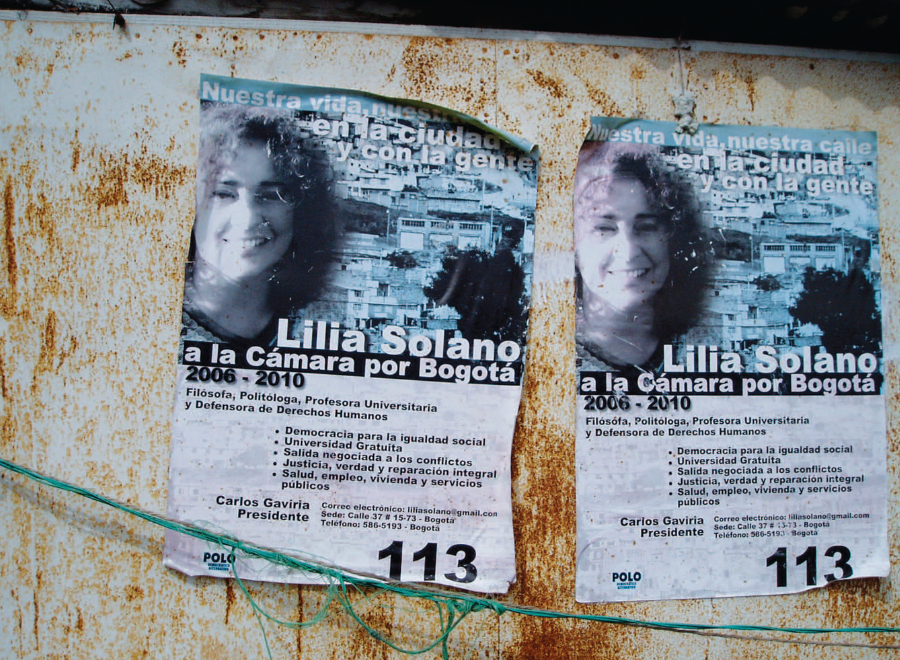

Other partners have jumped right into politics. Lilia Solanoa, a Mennonite human rights activist and president of the Justice and Life Project in Colombia, has twice sought elected office, addressing urgent issues of peace, justice and human rights. And in 2006, Maria Sumire of the Andean Women’s Association was elected to Peru’s congress as a member of an opposition coalition. When Sumire, a lawyer and member of Peru’s Methodist Church, tried to take her oath of office using her own language, Quechua, she was reprimanded by the presiding official — and gained certain fame as a result.

NEAR THE END OF THAT CONVERSATION with Jacob 25 years ago in the artisans’ co-op, Jacob smiled, leaned over and said, “Please, I invite you to join the great struggle for the liberation of the Haitian people.” Startled, I promised to do what I could and wished him good luck.

At a personal level, I chose to take Jacob’s invitation very seriously. It defined the course of my action as a journalist, a citizen and a Christian. It meant bearing witness to the stories of those who were marginalized and oppressed under prevailing economic and political systems, and confronting the supporters of those systems with the consequences of their actions.

At the political level, the Duvalier regime ended in 1986. That Haiti suffered subsequent dictators, two foreign interventions and is still impoverished does not mean Jacob was naive or misguided. The process takes time and Haiti’s liberation needs to be linked to changes elsewhere, including the richer countries to the north.

For social movements in Latin America and the Caribbean, this is a time of hope, but there are still risks ahead. Regimes that favour what Canadian author Naomi Klein has called “corporate supremacy” still abound, especially in North America and Europe.

And we’re talking about politicians here: the logic of power and holding on to it sometimes takes a toll on principles.

Some, like the Zapatista Indigenous movement in southern Mexico, call for a complete rethinking of concepts such as power and development.

Meanwhile, some people question how much of the social movements’ autonomy and leadership should be invested in partisan politics. But others respond that the poor do not have the luxury of caution: the impoverished must always take risks and try something new. For the first time in more than a generation, opportunities have presented themselves and they must be seized.

“Today is the beginning of privileges for the poor, for those without opportunity. We intend to overcome intolerance, inequality, discrimination and lack of solidarity,” said Guatemala President Álvaro Colom in his inaugural speech in January.

If everyone on this planet is to grow and thrive, we all require an end to practices that exploit social inequities. Social movements across Latin America and beyond will continue to work to make that vision a reality.

Jim Hodgson is The United Church of Canada’s program co-ordinator for the Caribbean and Latin America.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s March 2008 issue with the title “Revolution from the ground up.”