When you’re a reporter — as I have been for over 30 years — some stories seem to resonate more than others, and it’s rarely the blockbusters. For me, there are a couple of stories that really changed my perception of what’s important to our health, and the impact of our everyday interactions on our quotidian well-being.

In 2011, Judy Tak Fong Lam Chiu’s frozen and lifeless body was discovered on the sidewalk just 300 metres from her home in a frigid January. Chiu, then 66, believed to be in the early stages of dementia, left her comfortable suburban Scarborough, Ont., home in the middle of the night and ventured into the cold. She discarded her coat and glasses and wandered aimlessly. When she couldn’t find her way back home, confused and scared, she screamed for help. She banged on people’s doors and tried to claw her way into vehicles, setting off car alarms. Chiu died alone, her pleas ignored. The tale of her final hours was told through her footprints in the snow and the scratches on doors and cars. After her body was found, one neighbour recalled hearing the screams and another seeing a little old lady stumbling around in the dark. Neither offered to help, nor called 911 — they pulled the curtains shut and went back to bed.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Chiu’s preventable death is a reminder that, in modern society, isolation and loneliness are commonplace states of being that can have tragic consequences.

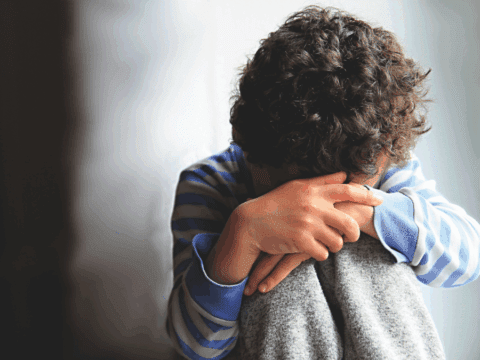

The second story is seemingly unrelated. Dr. Anne Snowdon, professor at the Odette School of Business at the University of Windsor in Ontario, examined the daily lives of disabled children and their caregivers. Unlike most studies, her work did not focus solely on health and social services, but also examined social interactions. The study found that 53 percent of disabled children had no friends. None. Outside the classroom, they spent less than two hours a week with their peers. They never played with other kids and weren’t invited to birthday parties — they were ostracized and isolated.

In Canada, we talk a good game about integration and about breaking down barriers to allow the inclusion of people with physical and social disabilities in every aspect of daily life. But reality is much harsher. Real integration requires a lot more than building ramps, adopting human rights legislation and funding programs — a dash of tokenism is not enough. Equality and equity require that people with disabilities be included in the banal activities of daily living, from the childhood playground and beyond. These accounts are a cruel reminder that many people in modern society, far too many people, are profoundly alone.

This hidden epidemic of loneliness is particularly acute in certain groups like the elderly, people with disabilities, immigrants and refugees, and the economically disadvantaged

This hidden epidemic of loneliness is particularly acute in certain groups like the elderly, people with disabilities, immigrants and refugees, and the economically disadvantaged — there is a reason they are often referred to as “marginalized.” It is also particularly acute, or at least more starkly evident, in certain environments, like big cities.

In his book Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design, author Charles Montgomery writes, “Social isolation just may be the greatest environmental hazard of city living — worse than noise, pollution, or even crowding.” Study after study deliver similarly grim prognoses: loneliness is as harmful to health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day; having no friends may increase the risk of premature death by about 30 percent; social isolation can be twice as deadly as obesity; it’s as big a killer as diabetes and it hikes the risk of dementia by 64 percent. Loneliness is a quantifiable health hazard.

Biologically, what’s happening is that the fear lonely people experience stimulates stress hormones (a reaction sometimes known as the fight-or-flight response), which in turn triggers inflammation, a major risk factor for heart disease. When that stress is constant, it also greatly increases the risk of depression and suicide. Being isolated often translates into being inactive, and that’s what increases the risk of obesity and diabetes. Loneliness is bad for your heart and bad for your soul, yet isolation is commonplace. More Canadians than ever live alone, and one in four of them describe themselves as lonely. An estimated one in eight seniors lives a solitary life without friends or family. The rates are even higher for people with disabilities, and those with severe mental illness. The homeless are, almost by definition, alone. For every lonely adult, there is a kid eating lunch by himself or watching from the sidelines as others play.

All told, it is estimated that about six million Canadians live an isolated existence. We have an epidemic of loneliness, and the principal underlying cause is poverty. If you’re poor, you’re six times more likely to be socially isolated than your peers. In academic circles, and increasingly in political discourse, the term “social determinants of health,” is bandied about. Sir Michael Marmot, the guru of social determinants research, defines them simply as the “causes of the causes of poor health.” What has the greatest impact on our health is not genetics or access to health care, but income, education, housing, food security and our physical environment. But there is one key health determinant that’s often forgotten: a sense of belonging. Being connected — to family, friends, neighbours, a community group, a running club, a mosque — can literally add years to your life.

The corollary is that isolation and loneliness are devastating to a person’s mental and physical health, deadly even. Isolation is, in part, a state of mind, but it is also a physical reality. So we need to ask ourselves how our surroundings, our homes and our cities contribute to the scourge of loneliness. Do we build cities — and adopt urban policies — that encourage social interaction or that breed isolation? Chiu’s story reminds us how urban design and social mores makes it easy, and even normal, to lock ourselves away and shut out others, particularly the most vulnerable. She died, in part, because she was anonymous, and seemingly neighbourless. The people on her street were merely occupants of houses and apartments, not neighbours or members of a community.

Society has changed a lot over a few generations, and many age-old support networks have broken down. Families are smaller and more spread out, so we are not surrounded by relatives. People live longer and move across the country for work, which makes us rootless. For many, the alternative to living alone is institutional living — particularly true for the frail elderly. There are 400,000 seniors living in “care facilities” in Canada. How many of them are lonely? Do we even consider the physical, emotional and social impacts of this mass institutionalization of our elders?

Social engagement has been commodified; it’s increasingly a privilege of wealth. Adult education, fitness programs and social activities like music concerts, dancing and bingo are expensive. Some of you may be thinking that we can overcome these barriers with technology. Chiu’s death, for example, sparked a discussion about the benefits of tracking devices like GPS ankle bracelets for dementia patients who wander. But tracking is not of much use in a life where there is no one who cares about your whereabouts.

If we want a sense of community, and its benefits, we need to invest in services that encourage independent living, and in public spaces and programs that nurture interaction. Yet, we underfund and devalue places that bring us together like libraries, parks, recreation centres and community gardens. We often make it difficult to volunteer with all kinds of bureaucratic hurdles. Being lonely also has stigma attached to it: it’s often associated with having poor social skills or being odd. We look upon those who are reaching out to make a connection with suspicion. How often have you heard: “How can I meet people?” For most, the answer to that question is not Tinder or Grindr.

This brings us to the plethora of virtual communities. How can anyone be lonely if they have 100 or 1,000 Facebook friends? The reality is that social media tends to make the lonely and isolated even more so — like hungry people staring through a window in at a lush buffet but unable to partake. The paradox is evident: we have never been more connected, or more adrift. We’re all scared of being alone, of not being loved or needed or cared about. And the lonelier we feel, the harder it is to reach out. Is that simply inevitable for a swath of the population? Is it a necessary byproduct of our fast-paced, dog-eat-dog society?

Isolation and loneliness can be avoided and countered with some sound and fairly basic public policies. In fact, research shows that the antidote to isolation is community building — using everything from urban design to educational policies in order to promote inclusion and a sense of community across economic classes. But what is this mysterious thing we call community? John McKnight, director of the Community Studies Program at Northwestern University in Chicago and author of the seminal work The Careless Society: Community and Its Counterfeits, defines our understanding of community: “To some people, community is a feeling, to some people it’s relationships, to some people it’s a place, to some people it’s an institution.” But the definition McKnight prefers is: “Community is a place where people prevail.” Can you say that about your city?

Building community takes determined effort. It takes time and money, and a conviction that it matters. It blossoms out of recreational centres, schools, places of worship, volunteer activities and in subtle gestures such as introducing yourself to your neighbours. It comes from reaching out to an old lady wandering the streets late at night, or to a boy in a wheelchair at the park. We often talk about inclusion and being senior-friendly, but what cities tend to offer are grudging accommodations — things like wheelchair ramps and discount bus passes. These gestures do not solve the problems of those who ride the bus all day because they have nothing else to do, or nowhere else to go. If we want people to be healthy — physically, mentally and emotionally — they need to be full citizens. If we want healthy cities, we need people to have a sense of belonging — not just a civic address. We need everyone to be engaged — not just the elite. We need to make a resolute effort to help each other, especially those on the margins of society, move from isolation to inclusion.

There is much poverty in our midst and many challenges for our cities. But there is also much hope, and many creative solutions and initiatives in communities all over the country. And in building a more inclusive society we can’t merely focus on those in obvious need; we can’t forget those who are invisibly alone.

As the late Mother Teresa reminded us, “Loneliness is the most terrible poverty.”

This story was originally published in the June 2016 issue of The Observer with the title “All the lonely people.”