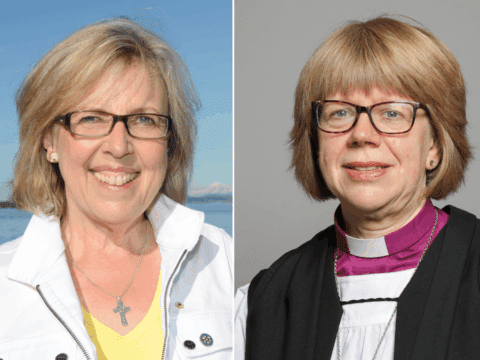

Last Christmas Eve, Rev. Susan Bell noticed a man sitting off by himself in the pews during her service at St. Martin-in-the-Fields, an Anglican church in Toronto. The man was distinctive looking: well dressed, bald head, glasses.

“I knew it was Michael Coren,” says Bell, associate priest at the well-known church. “He’s not in my circles, but I knew of him, that he had been on Christian TV and how his show was one to avoid. He was combative and very conservative.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Coren was not combative in her church — nor had he stirred any acrimony at St. James, the Toronto Anglican cathedral he’d attended regularly over the previous nine months. He sat humbly, contemplatively. What was he doing there? Hadn’t he written a book, Why Catholics Are Right?

That night, “He came up and took eucharist from me. It was a leap. We both knew it was a special moment.”

In the months that followed, Coren became a regular at St. Martin’s but mostly kept to himself. “For a long time, he didn’t say boo to a goose,” says Bell. “He was not really saying anything despite my trying to engage him; I think he was building up his own courage.”

Bell persisted, and Coren soon began confiding in her about his struggle, his hungering to refocus his Christianity around love. “Here he was, this poster boy for conservatism, thinking hard about being reoriented,” she says. Last April, he was formally received into the Anglican Church. “It was an amazing thing for me to be walking with him in this. I don’t want to be hyperbolic, but it was a Pauline moment.” As in St. Paul, Damascus bound, blinded by the light of the resurrected Christ.

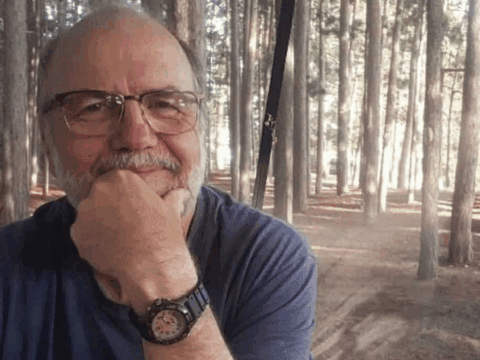

Coren, 56, has long been considered a darling of the political and religious right — and a thorn in the backside of the left. He first emerged on the public scene in the early 1990s as a belligerent right-wing pundit for the satirical news magazine Frank. His career as a professional provocateur grew to include stints as a TV host on Crossroads Christian television and the Sun News Network (now defunct); as a columnist with the Globe and Mail and the Sun newspaper chain; and as a radio talk show host and chief grenade thrower on stations like CFRB in Toronto. He’s also the author of over a dozen books, from literary biographies to polemical works like Why Catholics Are Right. For years he hewed the anti-same-sex-marriage line of evangelical Catholics.

His is a textured resumé, gilded with such honours as 2013 columnist of the year from the Catholic Press Association but also burled by much controversy and at least one firing (from CFRB in 2005).

But it’s the latest resumé entry that’s most surprising: Coren is now an Anglican and a supporter of same-sex marriage. A milder Michael is emerging, one who regrets many of the punches thrown in his past, who has gone on rounds of expiation, in a kind of sackcloth and ashes of gay-positive contrition. The new Coren is even considering becoming an ordained Anglican priest. (He was accepted to seminary, but deferred for a year. His book Epiphany: A Christian’s Change of Heart and Mind Over Same-Sex Marriage is due to be published next spring.)

Is someone with such strong views capable of change? Can Saul become Paul? Bell certainly believes so. It’s what Christianity is about. But others aren’t so sure. After all, this is Michael Coren we’re talking about.

I’d always suspected Coren’s often abrasive nature stemmed from some kind of youthful drama or unhappy home life, but it’s not so. He describes his childhood in the east London suburb of Ilford, U.K., as a happy one.

His roots are working class. His father, a Jew, was a London cab driver; his mother had no religion. Educated at the University of Nottingham, Coren wrote literary biographies and worked at the New Statesman magazine.

He came to Catholicism in his 20s, he tells me, “when I felt an undeniable presence in my life, all around me.” His Catholicism deepened with age and with love: he moved to Oshawa, Ont., in 1987 to be with Bernadette (Bernie) Barber, a Canadian Catholic whom he married later that year.

In Canada, he staked out a career in writing and media. His British taste for satire and cheekiness helped him land a job at Frank magazine, where he adopted the persona of an insufferably right-wing snob, “the Aesthete.”

“Really, it just grew out of the fun of puncturing some of the posturing of the self-important left,” he says. The character fed on its own energy, stoked by praise and more paid assignments, until Michael Coren, lye-mouthed gargoyle, had been created.

Whether he was penning columns or hosting TV panels, Coren was deliberately incendiary, writing things like, “Why is AIDS so special? . . . At its most simple, stop fornicating.” He called anti-Israel Jews at a pro-Palestinian rally “mentally handicapped.” On the debate over sexual orientation in the church, he wrote, “As for Jesus not condemning homosexuality, nor did He condemn bestiality and necrophilia. . . . Christ did indeed condemn homosexuality, as does the Old Testament, St. Paul, the church fathers and all Christianity until a few liberal Protestants in the last decades of the 20th century who, frankly, are more concerned with political correctness than truth.”

He’s written nasty things about the United Church and former moderator Mardi Tindal: “Do Mardi and her friends not realize just how dated and daft they sound? They toss around all of the old cliches like ‘new paradigm,’ ‘participate relationally’ and ‘safe place’ and then wonder why worshippers have abandoned their church quicker than a liberal Christian in a shoe store that has run out of Birkenstocks!”

If Coren’s arguments often seemed of a piece with the shirt-ripping lunacy of his contemporaries on the far right, it’s usually because of the viciousness of the tone, not the laziness of the thinking. His method was to sting with a reductive and sensational gibe, then follow it with something more qualified, more measured — balm on the wound, so as to be covered if challenged. Best of both worlds: he got the sound bite, the bang and the headlines but could comfort himself that, in context, he was a reasonable man. It was clever.

I’ve known Coren since 2006 when I began appearing, supposedly wearing the laurels of the secular left, on the now-discontinued Michael Coren Show, carried by Crossroads TV. In the green room before and after the show, another Michael Coren materialized. This one sowed a general teasing bonhomie among guests and panellists that did not differentiate by ideology. As he dressed for air, he would encourage a rolling ask-and-answer group colloquium — news of the day, personal updates, ideas considered.

I found it increasingly hard to dislike him quite as automatically as I should have, or even dislike him at all. Was I being buffaloed? If so, I wasn’t alone. One writer, in 1994, said, “It would probably come as a shock . . . that in private Michael Coren is quite personable. Likable even.” Broadcaster Daniel Richler called him a “softie” underneath the shell. Behind the scenes, Coren’s face changed. He looked less the Bond villain and more the Shaolin monk.

Even on air, I sensed this tugging in him: simultaneous but warring impulses to infuriate and to please, both feeding a need for attention and perhaps for love.

More than anything, I suspected that he was in deeper on the right than he wanted to be. “Lorrie Goldstein [the Toronto Sun columnist] would say it about me, if you looked at my positions, you could hardly call me a neo-con,” Coren says. He was anti-Iraq war, anti-death penalty and pro-union on various issues. “People just assume, but I was always a so-con [social conservative] more than a neo-con.”

On same-sex issues, especially, he was never as bitingly insulting to gays as he’s been to some others. When gay issues came up on the Crossroads show, there was a small but perceptible muting of the rhetoric. Though he hewed to the conservative Catholic line on homosexuality, it always seemed more doctrinal than visceral.

What turned him around as much as anything, Coren tells me, was when John Baird, then federal minister of Foreign Affairs, gave a tepid scolding to Uganda for proposing the death penalty for homosexuality. Even Baird’s small gesture was slammed by the anti-gay far right in an August 2013 statement. “That was pivotal,” Coren confides. “I was disgusted, physically.”

Over the course of the following year, he wrote several columns condemning Uganda’s and Russia’s anti-gay laws. Readers, sensing the change, were critical.

Then in June 2014, he wrote a column that appeared in the Toronto Sun under the headline “I was wrong.” In the column, while he doesn’t support same-sex marriage, he writes that he “saw an aspect of the anti-gay movement that shocked me. This wasn’t reasonable opposition but a tainted monomania with no understanding of humanity and an obsession with sex rather than love.” He calls for a new conversation in which “love triumphs judgment.”

The news media eventually caught wind of Coren’s increasingly public and vociferous support of same-sex marriage, his rejection of hardline Catholicism and his conversion to Anglicanism. In May 2015, Coren told the National Post, “I could not remain in a church that effectively excluded gay people. . . . I couldn’t look people in the eye and make the argument that is still so central to the Catholic Church, that same-sex attraction is acceptable but to act on it is sinful. I felt that the circle of love had to be broadened, not reduced.”

But his effort to realign his new inward values with his outward persona came at a cost. “The moment I came out,” says Coren, referring to the “I was wrong” column, “I forfeited $35,000 a year in income” from lost speech fees, regular column spots and other writing assignments. Over time, he was dropped by Sun Media, Crossroads, the Catholic Register and other Catholic publications. He has been accused, he says, of being gay himself, of cheating on his wife. “I’ve had people demand money back for books of mine they’ve bought.”

The timing of Coren’s conversion is a major sticking point for critics like Rev. Raymond J. de Souza, Catholic priest and columnist for the National Post. “It is not obligatory to announce to the world [you’re converting], but if you’re presenting yourself as a Catholic defender, it becomes important,” de Souza tells me. “He was still giving speeches and writing columns as a Catholic apologist” after he’d started attending Anglican services. De Souza says Coren “kept it secret” and “misrepresented” himself.

Coren agrees that he gave speeches and wrote columns during 2014, which was a kind of crossover period for him as a Christian. But he says he did so in a way that was entirely consistent with what was expected of him, and not critical of the Catholic Church. He denies being secretive or falsifying his position, and reflects that it’s “sadly sectarian” if Roman Catholics can’t read or listen to sympathetic voices from other perspectives.

De Souza also mentions Coren’s earlier flight from Catholicism. It came after a controversial story in Toronto Life magazine that Coren wrote in 1993 on then Toronto archbishop Aloysius Ambrozic. Stung by the backlash to that piece and disaffected with the church establishment, Coren left Catholicism in the 1990s. “I worshipped outside of the Catholic Church for about three or four years,” he recalls. “I did a lot of speaking so attended numerous churches [but was] not part of any denomination.”

He returned to the Roman Catholic fold with a vengeance in 2006. “He has a certain proclivity to change,” says de Souza, who wonders if Coren will at some point have a “third go” at Catholicism. De Souza chides him for being hurt by the backlash. “Michael, for his entire career, has been robust in the way he organizes his public positions. His stock in trade is being combative. But he has a kind of wounded response when people criticize him.”

There can be no doubt that the backlash to Coren’s conversion has left him wounded. “The attacks have been hateful, worse than anything I ever got from the left,” he says. “These are Christians? Where is the love?” And it is all, essentially, over his support of gay rights, pulled out from everything else. “I still believe in the virgin birth, that Christ is the Messiah.”

When I arrive at Coren’s house in the High Park area of Toronto in August, he greets me on the sidewalk. As if on cue, federal NDP incumbent Peggy Nash comes stumping along the street, campaigning.

“I’ll take a lawn sign,” says Coren to Nash. He’s voted for her before. Now he’s travelling in her left-of-centre sphere, forging new connections and gaining new assignments, including occasional columns for the Toronto Star.

Last June, he delivered a sermon at the Metropolitan Community Church of Toronto, a famously gay-positive congregation. He says the outpouring of forgiveness from the very people his words had hurt moved him to the core. This was the true candle of Christian faith; this was the kind of Christian he longed to be. He says he had to suppress the urge to weep the whole time he was there.

Sitting in his home office, Coren seems to have a deeply seasoned happiness about him. He shows me pictures of his family. They are a beautiful group: two girls, two boys, ranging in age from late teens to mid-20s. His wife, Bernie, is still Catholic.

Typically, his kids haven’t taken a great interest in the dramas of his professional life, but one daughter in particular was pleased at the latest developments. “It’s not so much my dad’s change on same-sex marriage that makes me proud, although it’s nice to agree for once,” writes Lucy, 24, in an email from France where she works in theatre. “It’s more simply the act of change itself. It’s a humbling and difficult thing to do — especially when he’s publicly supported something very different for a long time.”

She’s saddened but not surprised at the backlash. She knows how vicious her father’s critics can be. And here, Lucy makes a wonderful point, no matter what side you’re on. “It wasn’t insults that changed my dad’s mind, it was self-examination and reason. If you want to change his mind, be reasonable.”

When I learned of Coren’s conversion, it was like something in a novel for which there’d been foreshadowing. I’d be far more surprised if he went back to Catholicism, as de Souza suggests.

At least some of his raging gargoyle persona was shtick, a performer’s modus operandi. That doesn’t minimize or excuse the viciousness of many of his barbs but, honestly, I don’t think the barbs were meant so much to pierce the victim as to show how piercing their author could be. Still, they hurt. Coren has to wear that. Not meaning them to hurt fails as a defence. It’s why contrition has been such a big part of his conversion. “I regret so much of what I said, especially the tone,” Coren says. “I’ve said things I’m not proud of now.”

I believe him. I’m not sure anyone who knows him doubts his sincerity. He’s given up too much; he’s gained too much for it not to be real. I’m genuinely happy for him.

I ask him, in his office, if it feels liberating. He looks at me, his smiling face a kind of radiance unto itself, a central contradiction having been sorted out, a nagging hypocrisy finally expunged, a new peace in its place.

He says, as though it hadn’t occurred to him before, “Yes. That’s exactly the word. ‘Liberating.’ I’ve never been happier in my life.”