Miftodi Boca, 31, died on the last day of the Great War. A small black headstone just west of the town of Kapuskasing, Ont., now commemorates his short life. No one knows much about him, not even the proper spelling of his name. On the death certificate he is Iftodi Boca.

For most of the century, his modest grave was just a rotting wooden board at the side of the railway tracks. The Kapuskasing Internment Cemetery is still a grim spot, despite more recent efforts to dignify the grounds containing 32 graves. A commemorative statue and plaques were erected in 1995, along with the tidy lines of granite markers. The grass is maintained, but there is little other evidence that anyone ever visits.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The cemetery is a stone’s throw from the railway siding where Boca laboured, lived and died in captivity. He drowned in his own fluids at Kapuskasing internment camp during the Great Influenza pandemic of 1918 to 1919. The pandemic sickened half of the world’s population and killed at least 50 million people, including approximately 55,000 Canadians, including Boca. His crime? Being born Ukrainian.

It is not widely known that at the beginning of the First World War, under the War Measures Act (WMA), 120,000 recent arrivals to Canada automatically became enemy aliens — immigrants from any of the nations forming the Central Powers. Of these, 8,579 were interned during the war, many without trial under the draconian measures of the WMA. Some internees remained prisoners long after the end of hostilities. The Kapuskasing camp did not close until February 24, 1920 — one year, three months and 13 days after the end of the First World War.

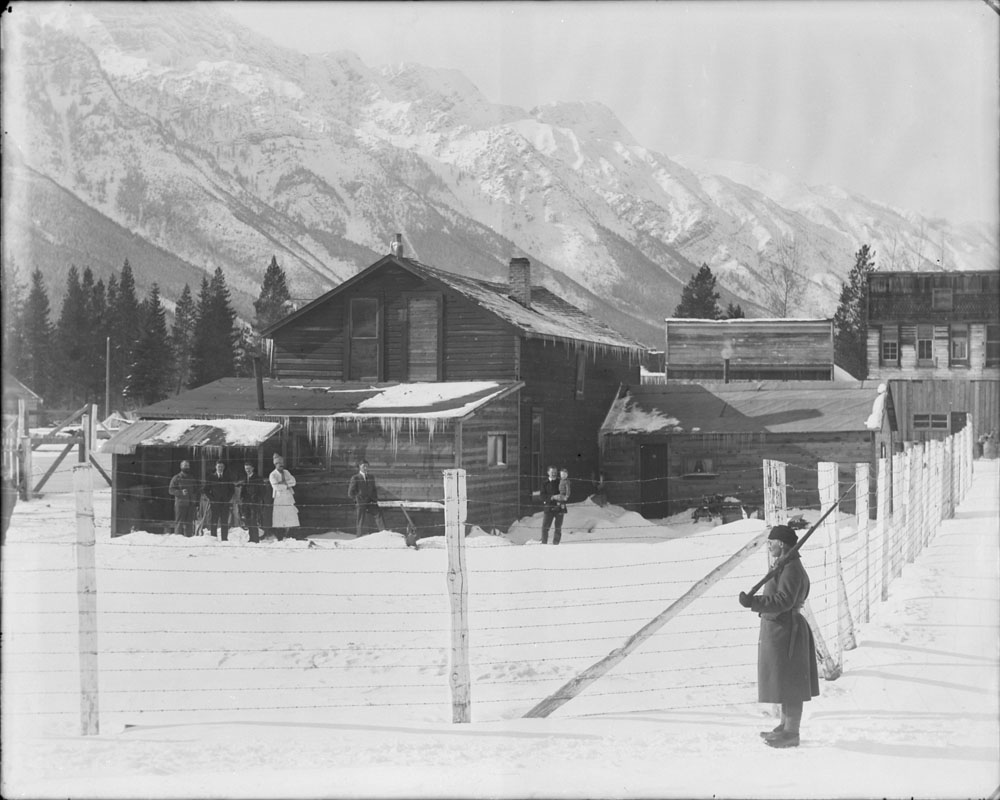

Most internees were poor and many homeless after failed attempts at homesteading drew them to towns and cities in search of work. They were arrested for failing to report as enemy aliens, for acting “suspiciously,” for being itinerant. They were incarcerated in 26 camps across Canada and forced into hard labour. In Kapuskasing, they cleared forest and stumped acres for an experimental farm. Others broke rocks, carved out roads with picks and shovels and built structures in the new national parks, including Banff and Jasper. They also cleared land for tennis courts and golf courses. Prison numbers replaced their names.

More on Broadview: We don’t seem to be learning from HIV/AIDS

The camps were run by the military and the internees were considered prisoners of war. The majority, some 5,541, were from the Ukrainian territories of Galicia and Bukovyna, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and hence, enemies of the Entente powers. Most internees were single men, but some women and children were also incarcerated.

The conditions were appalling. In Kapuskasing camp, the water was not even potable, drawn from the same river into which raw sewage from the latrines drained. A lab report from September 1918 deemed it “absolutely unfit for drinking purposes.” Hungry, exhausted internees, pressed into hard labour, housed in drafty, cold buildings with insufficient clothing, bedding or medical care, sometimes working in temperatures as cold as 50 below, were already severely physically depleted long before the deadly second wave of influenza hit the camps in October 1918.

The Temiskaming Speaker reported as early as Halloween that there were severe cases in the north, with “the Kapuskasing camp being probably the greatest sufferer.” George Macoun was a guard there. In a letter home he gives an account of the epidemic but says little about the prisoners. Those details he does provide are brief yet chilling. He describes two shacks used as a “hospital” for the prisoners where “they were cared for by their own comrades.” There were no nurses or doctors among the imprisoned population. In other words, sick internees fended for themselves.

Influenza hit all of the internee camps, and the railway work parties where they toiled across the country. It was particularly nightmarish for a work detail in P.E.I. In a December 1918 report to the commandant of Internment Operations at Amherst Internment Camp, Lieutenant R. Dunbar complains about the horrific conditions for his guards and internees on the railway line and how little in the way of supplies or help were available. At least 15, including Dunbar, got sick.

The leaking boxcars, where the men slept, reeked. Guards and internees tore up floorboards to discover six inches of animal and human excrement. Dunbar pleaded for a clean car to be sent for the sick but none arrived for weeks. His wife ended up cooking and delivering food daily or they could have starved, as local farmers refused them. The report goes on to detail the trouble Dunbar had securing even drinking water. In this instance, had it not been for the determination of one sick officer and his wife to secure the bare necessities of life, and the help of a local Catholic priest, the outcome would certainly have been worse than it was, with three dead.

In all, 126 internees died in the camps: 59 in Ontario and most of those, 32, at Kapuskasing. It is only now that we can work out how many died of influenza during the pandemic. Historian Lawrna Myers of Vernon, B.C., undertook to find every death certificate and grave of those who died in the camps. My analysis of that data indicates the pandemic killed a minimum of one quarter and possibly up to one third of all internees who died in the camps, far more than any other illness or injury. The numbers could be even higher, given that influenza was doubtless a contributing factor to the demise of those who died officially of pulmonary tuberculosis and other related causes during the pandemic.

The death certificate of Iftodi Boca, the Ukrainian who died on November 11, 1918, stated the cause of death as bronchial pneumonia following influenza. He died not knowing the war had ended, that he would be freed — perhaps only to be repatriated against his will. Today, largely through the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund, the abuses suffered by Boca and other internees are becoming more known through public memorials, education projects and online resources. Perhaps their names and stories won’t be forgotten after all.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

The article doesn’t mention that there was an internment camp for Italians — also considered prisoners of war, although many were long-the Canadian residents — in Yoho National Park, just a little down the Kicking Horse River from Field, BC. No traces of it remain today.

Sad but great piece. Thank you.