The plan for my visit to Walden Pond in Concord, Mass., is to plunge into its deep, still waters. Simply dipping a toe in won’t do — my secular baptism will require a full immersion in one of America’s most iconic ponds, made famous by writer and philosopher Henry David Thoreau, who experienced a spiritual awakening when he moved to its shores at age 27 on July 4, 1845. He lived alone here for two years in a small house he built himself, and often started his day with a swim. “I got up early and bathed in the pond; that was a religious exercise,” he wrote in Walden, his masterpiece of non-fiction published in 1854, which urges readers to live simply, intentionally and in harmony with nature.

Thoreau’s ideas are as relevant now as they were 150 years ago. He’s considered a major influence on modern ecology, the grandfather of the simplicity movement, a hero of social activism and the inspiration for forest therapy and tiny-house living. More than a dozen books about him were published last year for the bicentennial of his birth.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

A lapsed Unitarian, Thoreau chose the woods over the church, trading the hard pew of the cathedral for the spires of the arrowy white pines that surrounded his 10-by-15-foot cabin. He believed the best cure for just about anything was the “tonic of wildness.” His hours were spent walking, playing his flute, writing in his journal and scrupulously examining every bit of flora and fauna as if they held the mysteries of the universe. To him, they did. He had a poet’s soul and a scientist’s eye.

The son of a pencil manufacturer, he graduated from Harvard and later earned a living doing occasional work as a handyman for $1 a day. Walden’s initial print run was 2,000 copies, but it has since become a spiritual guide for millions, beloved for its indictments of modern society, dreamy musings and urgings to focus on the things that really matter.

Thoreau wrote “a sacred book for the modern age,” Laura Dassow Walls, author of the 640-page biography Henry David Thoreau: A Life, said in a lecture. “An age of expanding railroads and global industrialism, rampant consumerism, mass migration and the exploitation of workers . . . slavery and [Native American] genocide, the Mexican war and environmental destruction. In other words, a world an awful lot like our own.”

Thoreau’s words still resonate today, and so too his presence is still felt in Concord, the small New England town where he lived most of his life, a half-hour’s drive from Boston. It attracts 700,000 visitors a year, many of them pilgrims who swarm the famous pond in summer, creating the kind of crowd Thoreau did his best to avoid. They head to the Walden Pond State Reservation to walk the 2.7-kilometre trail circling the 25-hectare pond and to see the exact replica of his cabin, which features a bed, desk and three chairs — “one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.” At the Concord Museum, they can view 250 Thoreau artifacts, including his walking stick, flute and spyglass, as well as the simple green-painted desk where he wrote each day. They might book a room at the historic Colonial Inn, once owned by Thoreau’s grandfather, or dine at the upscale earth-to-table eatery 80 Thoreau, where a good bottle of wine will set you back a whole lot more than the $28.12 Thoreau spent to construct his cabin.

Perhaps some will even attend a Sunday service at First Parish, the Unitarian Universalist congregation Thoreau quit when he was 23, preferring to spend his Sabbaths searching for chestnuts or leading a huckleberry party. Still, when Thoreau died of tuberculosis in 1862, the church honoured him by ringing its bell 44 times, one for each year of his life.

“Though it stings a little to realize that Henry did not want to join us, we have forgiven him his standoffishness because we like the other things that he did and said,” Rev. Howard Dana preached from the pulpit of First Parish for Thoreau’s bicentennial. “We like how his activism encourages us to stand against injustices in our day. We like how his love of nature calls us to the woods ourselves. This favourite son, this wayward child, this prophet in our midst — this much-loved Thoreau — also represents a deep ambivalence towards organized religion that we also share.”

First Parish stands in the centre of a town that’s famous for two revolutions. It’s the site of the first battle of the American Revolution — the famous “shot heard round the world” fired between the British and local militiamen on April 19, 1775, on the North Bridge, now part of Minute Man National Historic Park. It’s also a birthplace of the 19th-century philosophical, spiritual and literary revolution known as transcendentalism, a movement centred around a close-knit group of writers and intellectuals who represented the most original minds of their time. Led by the famous philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, they included Thoreau, the educator Bronson Alcott, his daughter Louisa May Alcott (author of Little Women), journalist Margaret Fuller and Nathaniel Hawthorne (author of The Scarlet Letter).

A popular misconception is that Thoreau was regarded as a recluse and a bit of a crank by his fellow Concordians, but he was actually very sociable, making the 20-minute walk from his cabin into town every couple of days to visit these friends. The lives of this remarkable “genius cluster” were deeply intertwined — they challenged and inspired each other, sharing both their writing and their countercultural views on a whole new way to experience God. They’d stroll under Concord’s lofty elms discussing their lofty ideas — which sounds idyllic until you consider some of them struggled with financial hardship (often relying on the largesse of the wealthier Emerson) and faced the early deaths of their children, spouses and siblings to common Victorian diseases, such as tuberculosis, scarlet fever and lockjaw (tetanus). Death was a constant presence that spurred them to seek a kind of heaven on earth.

Today, their Concord homes are museum attractions. The Alcotts’ Orchard House, where Louisa wrote her famous novel, is down the road from the Emerson House. Nearby are the Old Manse and the Wayside house, homes where Hawthorne lived and worked. With such a powerful circle of brainpower in Concord, it’s not surprising that writer Henry James called it “the biggest little place in America.”

The transcendentalists rejected organized religion, the concept of original sin and the idea that Jesus was anything more than a worthy role model. While the Unitarians thought people were born basically good, the transcendentalists pronounced humans, and all beings, divine. They believed God was revealed through nature, that the real miracles, in the words of Emerson, were “the blowing clover and the falling rain.” Instead of relying on biblical authority, they relied on themselves, insisting that spiritual truth is known intuitively rather than through institutions, and that one could “transcend” reason and rationality through sensory spiritual experiences.

“The transcendentalists were responsible for introducing the distinction between religion and spirituality,” Rev. Barry Andrews, author of Transcendentalism and the Cultivation of the Soul, said at a Harvard Divinity School event in September. “Thoreau eschewed religious institutions, but was a deeply spiritual person. And this is one of the reasons that many people today find him so appealing. He may have been decried as a heretic and an atheist in his own time, but now he is viewed as the avatar of an alternative way of being religious in the world.”

Thoreau and his fellow transcendentalists were, in fact, the original SBNRs — the demographic known as “spiritual but not religious,” which in 2017 accounted for 27 percent of the American population. But back in the mid-1800s, it was a very rare — and very radical — religious subset. First Parish’s Dana describes the transcendentalists as people who “pointed us away from a carefully orchestrated church life to a messy, wild spiritual life, unconcerned with either salvation or social standing.”

These spiritual seekers and political activists didn’t conform to the stereotype of the stiff New Englander. They were the hippies of their day, influenced in part by Eastern religions. They believed self-actualization leads to enlightenment and, potentially, utopia here on earth. Above all, they were idealistic individualists. “To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment,” wrote Emerson, who urged self-reliance in all matters, including religion. “Make your own Bible,” he wrote. “Select and collect those words and sentences that in all your readings have been to you like the blast of a trumpet.”

Just as today’s SBNRs are often dismissed, the transcendentalists were often derided. Edgar Allen Poe described them as “Frogpondians” for their quirky croakings. As recently as last year, a Boston Globe writer dismissed them as “navel-gazing, teetotaling grouches whose idea of a good time was waiting for the frost to form on a stand of lily pads.”

The transcendentalists were certainly dreamers, but they were also people of action. Thoreau sheltered slaves on the Underground Railroad and gave speeches and published articles calling for the abolition of slavery. Margaret Fuller advocated for women’s rights to work and to higher education. Bronson Alcott was a founding member of the Non-Resistance Society, which opposed all forms of violence. Thoreau decried the fact that “the luxury of one class is counterbalanced by the indigence of another.” He retreated to Walden Pond but did not retreat from the pressing social issues of his day — he stopped paying his poll taxes in protest of his government’s support of slavery. This landed him in the Concord jail for a night, an experience that inspired him to write his famous “Civil Disobedience” essay, cited by both Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. as an inspiration for their non-violent actions.

Writing in the Guardian in 2011, Wen Stephenson argues that Thoreau’s commitment to activism should inspire us today, especially when it comes to climate change. “If slavery was the human, moral crisis of Thoreau’s time, then global warming . . . is the human, moral crisis of our own,” he writes. “There’s still time — if we act — to preserve a livable planet for our children.” It may seem hopeless, “but then, abolishing slavery sounded hopeless in 1854.”

One can’t help but wonder what Thoreau would have to say about the current U.S. administration, which balefully denies the physical science of global warming even as glaciers retreat, sea levels rise and extreme weather events cause death and destruction. Surely his fingers would pound out damning words to criticize such idiocy, and his feet would take to the streets to march in protest.

In death, as in life, Thoreau’s cluster of friends remains close. The transcendentalist movement faded when they died, but their graves are separated by mere yards in the section of Concord’s Sleepy Hollow Cemetery known as Authors Ridge. Emerson’s tombstone, a large rough-hewn boulder of rose quartz, towers above them all. But it’s Thoreau’s tiny stone, marked simply “Henry,” that’s the biggest draw for pilgrims who leave offerings of pinecones, rocks, pennies and notes inscribed with his famous sayings. They stab pencils into the earth around his headstone, a tender gesture to this pencil-maker’s son whose written words have left such a lasting impression.

From beyond the grave, “Thoreau speaks to us like a prophet,” says Lori Erickson, a travel journalist and Episcopal deacon who includes Walden Pond as one of a dozen sacred sites from around the globe in her new book, Holy Rover: Journeys in Search of Mystery, Miracles, and God. “As with all prophets, the full worth of his words are only appreciated with the passage of time.” One of Thoreau’s most important lessons, says Erickson, is that he proved “you don’t have to go far to be a pilgrim. You can go to Jerusalem, but you can also go to the nearby woods.”

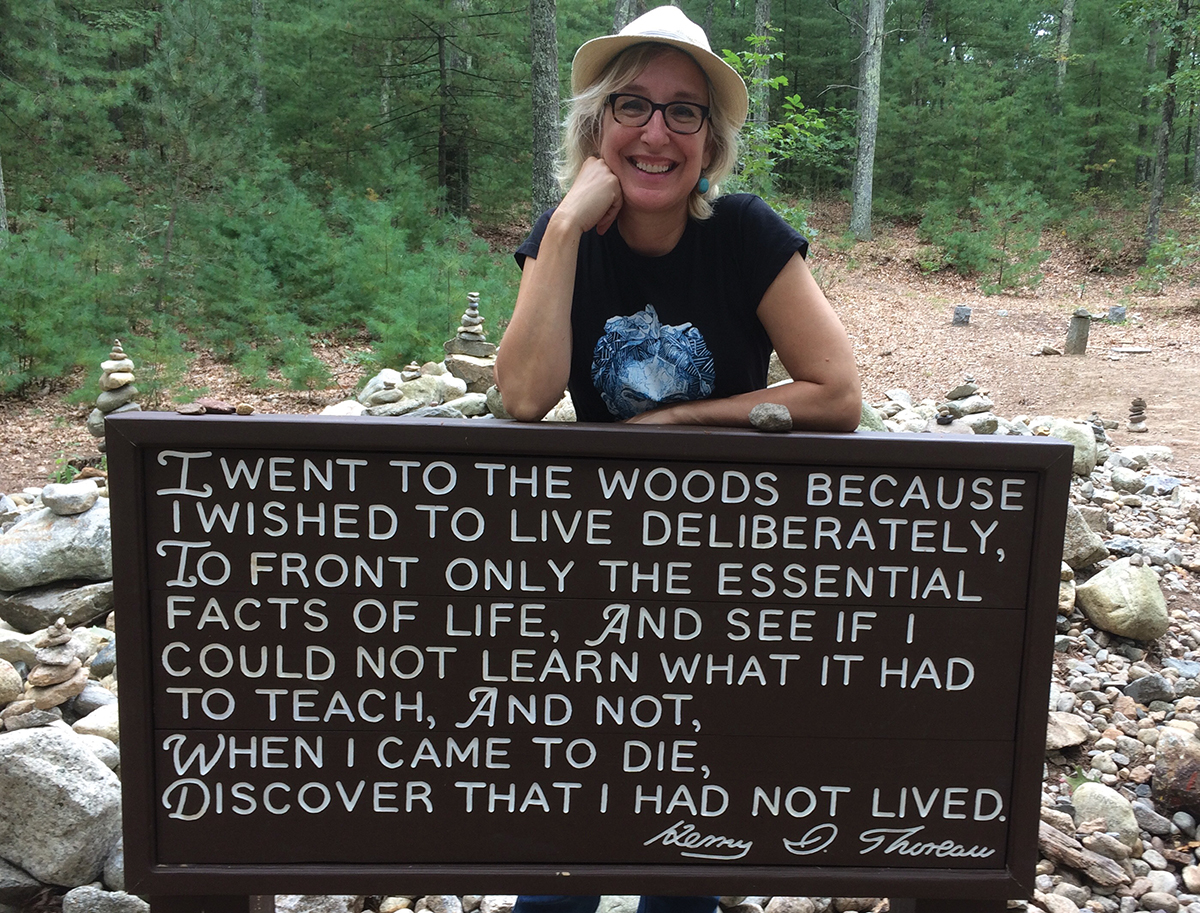

Walden Pond is a five-minute drive from Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, and it’s teeming with life on the day I arrive in early fall. Children are playing with sand buckets on its shore, and several swimmers are moving vigorously along its surface. A couple of boaters cast lines into its clear depths. I pass a dozen or so hikers as I make my way around the pond’s circumference to lay a stone, like many before, at a memorial cairn of rocks near the original site where Thoreau’s cabin once stood. A large wooden sign proclaims his intention for his sojourn here: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Standing barefoot on the small pebbles at the edge of the pond, I look out at the clean, clear expanse of this very ordinary body of water that has become such an extraordinary destination, a site that serves as a symbolic reminder to protect the planet we love. I consider Thoreau’s particular talents, how he was so connected to nature that he could summon a woodchuck with a whistle and distinguish the calls of the wood thrush, the scarlet tanager, the field sparrow and the whippoorwill — the “thrilling songsters of the forest.” As if on cue, a heron flies overhead, its wide wings outstretched in seeming benediction. I’m startled when it’s followed a few minutes later by a trio of helicopters, headed for the local airbase. The loud, rhythmic whirring of their blades threatens to burst my bubble of tranquility. I try to ignore the sound and heed Thoreau’s instruction to “live in the present, launch yourself on every wave, find your eternity in each moment.”

Soon the air is still again. I brace myself for my immersion and wade into the cool, refreshing water, ready to be born again.

This story first appeared in The Observer’s February 2018 edition with the title “Return to Walden Pond.”