This spring, as churches, the federal government and Indigenous groups prepared to take part in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission into Canada’s residential school legacy, the words of Bob Watts began to ring true. A year ago, Watts, the interim executive secretary of the commission, told a conference that “before the truth can heal, it may hurt,” and that reconciliation “may be a messy task and it may bring out uncomfortable truths.”

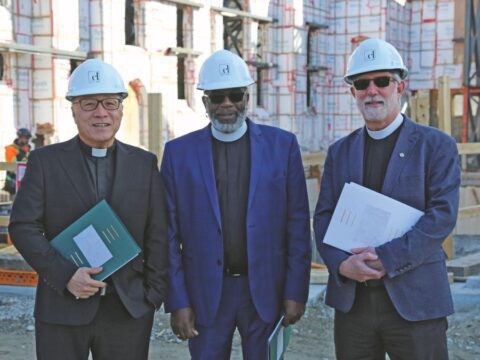

For the United Church, the task initially meant confronting sensational allegations from Kevin Annett, a self-styled crusader, filmmaker and former United Church minister. In March, as Moderator Rt. Rev. David Giuliano and other church and Aboriginal leaders toured Canada to build momentum for the coming truth and reconciliation process, Annett and a small group of Indigenous supporters picketed Toronto church offices and briefly occupied the city’s Metropolitan United. They demanded information about children who died at residential schools and called the schools an “Aboriginal holocaust.” Later, the group announced its own inquiry into 28 sites across Canada alleged to be “mass graves” containing the bodies of Indigenous children.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Annett, who resigned as minister of St. Andrew’s United in Port Alberni, B.C., in 1995 and was subsequently delisted from the United Church’s ordered ministry, has alleged United Church involvement in pedophile rings, murder and secret burials, as well as church and government cover-ups. The General Council Office has twice issued statements refuting many of Annett’s claims. Now, it is helping to formulate a response to his oft-repeated assertion that upwards of 50,000 Indigenous children died or disappeared at about 130 church-run residential schools. Messy indeed.

Denying allegations of conspiracy is difficult in the best of circumstances because the accuser can label the very denials as further evidence of conspiracy. Most of the churches or religious groups that operated Indigenous residential schools readily admit the institutions were miserable failures that robbed children of family life, language and culture, and often exposed them to physical and sexual abuse. On its website, the United Church “recognizes the tragic reality that. . . Native children died as a result of illness, disease or accident.” It is now part of a team of government and church archivists trying to determine who, where and how many.

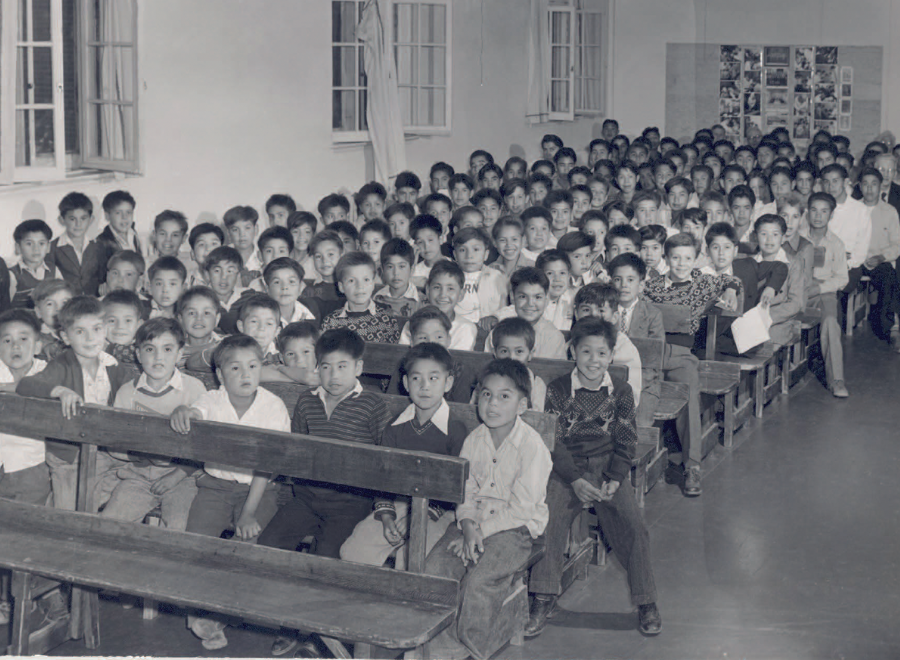

Various Roman Catholic groups ran the majority of schools; Anglicans ran about a quarter. Presbyterians and the United Church account for about a fifth of the institutions. Gaps exist in the documentary record of the century-long history of residential schools, so total student population estimates range from 80,000 to 150,000; the widely accepted figure is now 100,000. By the mid-1940s, about half of school-age Indigenous children were in residential schools, but by the 1950s — with a 96 percent high school dropout rate — the institutions were falling out of favour. By 1960, 22.4 percent of Indigenous children attended.

Last year, 86,000 residential school survivors applied for payments from the initial “common experience” portion of the overall $4.5-billion settlement that churches, Indigenous groups and the federal government finalized in 2006. So far, 68,000 survivors have received payments averaging $17,647.

Once Truth and Reconciliation commissioners are named and five years of hearings and reporting begin in earnest, survivors, their families and communities will be able to tell their stories, creating “as complete an historical record as possible” of the residential school system. The commission will not act as a formal public inquiry. Witnesses will be able to name abusers or victims, but only during sessions out of the public eye. Should allegations of criminal activity come to light, the RCMP will undertake its own investigation.

First, though, church archivists will comb their records in search of information about children who died or went missing at the schools. A working group made up of commission staff, First Nations organizations and survivor groups is figuring out how to complete that work.

Last fall, the United Church convened a meeting of its own archivists. Once a common research format has been adopted, the church will hire a researcher to undertake the estimated three months of work, largely in national and Conference archives.

The central United Church archives were being moved this spring from their former home at the University of Toronto to a first-floor location at the General Council Offices in Toronto’s west end. But residential school records have been continuously available, says United Church chief archivist Sharon Larade.

Searching for missing students, though, is not easy. “The challenge,” says Larade, “is that you are looking for someone who is gone . . . by virtue of absence on the lists. And we don’t have a set of names of students who went missing.”

Researchers will look for mentions of missing students in written reports or from community anecdotes. Quarterly reports listing residential school students — the most comprehensive lists — went to government agencies and are not in church archives. But even these have widely acknowledged gaps.

Research to verify student attendance for initial settlement payments has already exposed missing records from the 1940s and 1950s. Records may have been lost, destroyed in school fires or thrown out in “sampling” to reduce the volume of documents, says Larade. Where direct records such as government quarterly reports are not available, indirect references such as yearbooks or newsletters have helped to fill in the gaps.

Records for students who died at schools or were buried in cemeteries may likewise be found in a variety of locations.

United Church residential schools in Brandon, Man., and Edmonton had their own cemeteries. But in Edmonton, the burial ground was also used by the Charles Cansell Hospital. Students from Edmonton have reported witnessing burials, but it is not clear whether those being interred were students or hospital patients.

Schools without their own cemeteries may have buried students at community cemeteries, says Rev. James Scott, General Council officer for the church’s residential school steering committee. Students’ bodies may have been shipped home, he says, “but it’s reasonable to assume that in a number of cases, they were buried locally even if they had come from far away. It’s all part of treating people as if they are not important. It’s part of the whole system, really.”

It’s the sort of uncomfortable truth for which the church has already apologized and for which it is now trying to make amends. Whether the treatment of students in church-run schools extended to murder or burial in unmarked graves, as has been alleged, is still not known.

ABOUT 250 PEOPLE HAVE BRAVED THE COLD and wind-whipped snow to attend a meeting of Kevin Annett’s “Truth Commission into Genocide in Canada” in a downtown Toronto auditorium last winter. Annett and his supporters have plastered the walls with hand-drawn posters. “Full access to church files now!” demands one poster. “Bring those responsible to justice now!” declares another.

A clip is shown from Annett’s documentary film, Unrepentant, that links his long-running feud with his former employers in The United Church of Canada to his allegations about murder, medical experimentation, forced sterilization, pedophile rings and secret burials in residential schools.

Then Annett — or Eagle Strong Voice, as he’s known to some supporters — comes to the podium. His delivery is self-assured and low-key. Terms like “torture” and “crimes against humanity” and “mass murder” slip seamlessly into a 15-minute talk supported by overhead projections of archival documents Annett says prove that the government of Canada and the churches that ran residential schools set out to decimate the Aboriginal population by deliberately exposing children to diseases such as tuberculosis. The talk ends to warm applause.

A few days earlier, his supporters presented Gov. Gen. Michaëlle Jean with a letter to Queen Elizabeth demanding that as sovereign she “publicly disclose the cause of death, and whereabouts of the buried remains, of all children who died in Indian Residential Schools operated by the Church of England in Canada, a.k.a. the Anglican Church,” or face a lawsuit. Similar demands have been sent to the Vatican, the United and Presbyterian churches and the prime minister.

The United Church response reaffirmed the denomination’s commitment to the truth and reconciliation process and strongly disputed Annett’s claims in the media that the churches were ignoring his demands.

Many of Annett’s allegations about the United Church centre on the Alberni Indian Residential School, run by the church and its predecessors from 1891 to 1973. No one defends that school’s record for student care: Arthur Henry Plint, a dormitory supervisor during the 1950s and ’60s pleaded guilty in the mid-’90s to 36 counts of sexual assault.

Accusations of murder and unmarked graves, though, seem unlikely. Alvin Dixon spent eight years at the Alberni school in the late 1940s and early ’50s; he now counsels residential school survivors in Victoria. During his own school years, he didn’t see or hear about any student deaths or burials. Nor has anyone been charged with crimes at Alberni since Annett began making accusations.

Port Alberni RCMP Corporal Rob Foster, the officer in charge of Indigenous policing, says it would be “inappropriate” to say whether or not the detachment is actively investigating suspicious deaths or burials at the school, but “that sort of complaint would definitely result in an investigation.” Whether or not there was such an investigation —unconfirmed reports circulate of a fruitless police search for graves on the former school property — no charges have been laid.

Dixon says there’s little doubt children died at residential schools, but in helping “hundreds and hundreds of survivors” fill out claim forms, he has encountered “maybe three such incidents where people have clearly said they know of one or two people dying either through mishap or abuse. And in one or two incidents, they may have been buried on site.

“I can’t relate to the numbers that are being thrown around,” says Dixon, “but that doesn’t mean there weren’t many.”

Preliminary research by Anglican archivists, says Larade, “identified somewhere between 100 and 200 students who had died at school.” Whether the total number of students who died is in the hundreds or thousands, Rev. David MacDonald says naming and finding them is important.

“In many of the Aboriginal traditions, there is a need to allow the spirits to return home,” says MacDonald, who helped to broker the 2005 settlement deal and works as a consultant for the United Church. “So people need to know if there is a place where some of the students at these schools have been buried and to have some sense of closure for the families and the communities.”

It’s messy, uncomfortable and painful, but all part of the truth that may lead to healing for churches, Indigenous Peoples and their communities. In March, still waiting for the federal government to name commissioners, Bob Watts said the pain and effort should prove worthwhile.

“This is really an unwritten and unspoken-about chapter in Canada’s history that has had profound impacts. . . . So it’s important that it be understood and that we find some ways forward.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s May 2008 issue with the title “Reconciled to hard truths.”