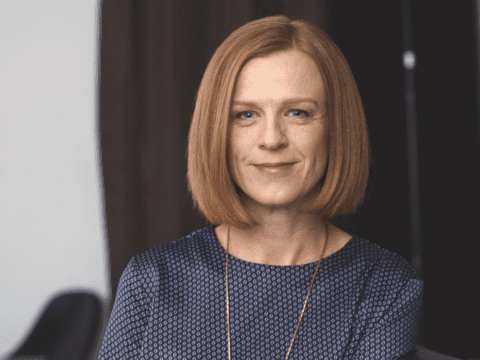

Nadia is celebrating her 36th birthday, hosted at her hipster friends’ hipster apartment in New York City. Nadia is high, drunk, melancholy. Her life is a mess. She goes to the bathroom for some privacy. She sneaks out of the apartment. She dies. Seconds later, she is alive again, back in the bathroom. Over the course of eight episodes, Nadia dies many times. She falls off bridges and railings, gets hit by a taxi, gets blown up, has a heart attack — and each time she returns to the bathroom, ready to live through yet another version of her final minutes. This circularity drives the first season of the critically acclaimed Netflix series Russian Doll, which was released in February.

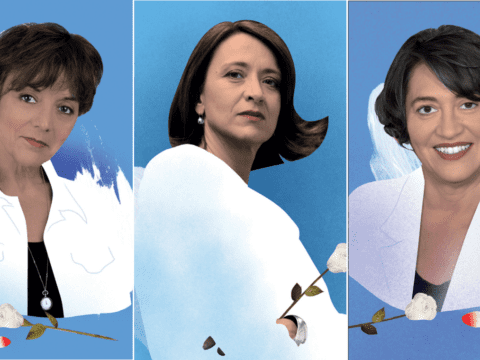

Meanwhile, on The Good Place, a sitcom currently airing its fourth and final season on NBC, four people die and end up in a colourful purgatory filled with witty one-liners and extended philosophy lectures on living morally. The four new arrivals have all lived less-than-perfect lives, but, like Nadia, they get many more chances to do better. Over the course of the series, they go through multiple lives in the hope they can earn their way to what they call the good place.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The premise of both shows is clearly reminiscent of Groundhog Day, the classic 1993 movie in which a complete jerk named Phil, played by Bill Murray, is stuck in his own time loop, waking up to the same day and reliving the same moments until he learns how to love. At first, Phil uses the opportunity to exact revenge on those he feels have wronged him. But slowly, over the course of 12,395 consecutive Groundhog Days, he begins to correct the wrongs he himself has inflicted on others.

More on Broadview: 7 contemporary takes on the 7 deadly sins

These are just a few examples of the many television shows and films that play with the idea of time’s recurrence — myriad shows about myriad chances to correct bad life choices. Why is this narrative structure so common? Why are we so stuck on stories where time repeats itself?

One possibility is the declining influence of religion. The struggles these characters go through — finding meaning, gaining understanding, becoming better people — these all used to be projects informed by faith. Contrition, prayer, confession and redemption were part of the solution. But in nearly all of these shows and films, there is a noteworthy lack of divinity — even The Good Place styles its version of heaven in areligious terms.

These are stories for a secular age. With no God to provide meaning or moral guidance, the characters are forced to work out their redemption on their own, and the mutable and recurring temporality they inhabit offers them a chance to do just that through an endless series of trial and error.

And so it is with Nadia, plus the four struggling to get to the good place. Their first task is to acknowledge that they are not good people to begin with. On The Good Place, one character is indecisive to the point of alienating friends. Another uses good works to prove herself a better person. A third is just nasty, like the Murray character in Groundhog Day. The fourth is a dolt. All have to overcome their own nature, their own habits, to be better people. And so they are rebooted over and over, each time coming a little closer to self-realization. The process feels like psychotherapy, which is also a theme in Russian Doll.

With no God to provide meaning or moral guidance, the characters are forced to work out their redemption on their own.

The idea that time is circular, that our lives and our histories repeat themselves, is an ancient one. But perhaps one of the most provocative formulations of the idea comes from Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th-century German philosopher. He also introduced the idea in the context of the search for meaning without God. He called it “eternal recurrence,” and argued that those who welcomed the opportunity to endlessly repeat their lives, despite hardships, were the most commendable.

Much of Nietzsche’s work was concerned with discarding and overcoming the theology and morality of Christianity. While not himself an atheist, he famously declared, “God is dead.… And we have killed him.” It was a critique of religiosity. In God’s absence, Nietzsche believed we must create our own morals and our own values, striving to affirm and celebrate even the most harsh, difficult and seemingly meaningless experiences we face, because they are all we have.

Upon learning of eternal recurrence, “would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth?” Nietzsche asks his reader. Most of us, perhaps, would. But Nietzsche most respected those who could joyously affirm an eternity in this flawed world instead of expecting another, better, one.

Nietzschean time loops, then, are the philosophical theory that informs many of these TV shows and movies. In fact, the philosopher is quoted verbatim in The Good Place, when one of the four main characters echoes word for word Nietzsche’s own concern with how to create meaning without God.

It is especially illuminating to consider these time-loop dramas in the context of contemporary media consumption, and the streaming services that allow endless repetition of experience through binge watching our favourite shows again and again. When we re-watch these shows, we are slowing the march of time, constructing our own eternity. We are reliving our own lives through streaming media.

This is not exactly what Nietzsche envisioned. For him, reliving “every pain and every pleasure” leads to that “one hour where, for the first time one man, and then many, will perceive the mighty thought…of all things.” He is a severe, sometimes dour thinker. Unlike the characters in contemporary time-loop dramas, he does not hold out the hope for self-improvement, but something possibly more interesting — a true enlightenment.

Instead, we have our light entertainments softening the edges of old philosophies. A century after Nietzsche, many of us are still working out how to live without God. And for some, on-screen fantasies are a way of working out our purpose.

This story first appeared in Broadview‘s December 2019 issue with the title “Stuck in a loop.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Although I would probably never watch these shows, I could only think of one thing and it was summed up this way:

Upon learning of eternal recurrence, “would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth?”

Matthew 22:13 Then the king said to the servants, ‘Bind him hand and foot, and throw him into the outer darkness; in that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth’

Here Jesus describes Hell. It is here those who do not believe the Gospel of Christ will spend eternity reliving their lives eternally wishing they could “do it over again”.

Thank you for the article. A comment on the question you posed to the readers “why are we so stuck in stories where time itself repeats”. You suggested that its philosophical root is based on Nietzsche’s “God is Dead” philosophy and on a specific sub concept within it called eternal reoccurrence. I believe you are making a stretch when you say Nietzsche admired those who could create their values without the moral underpinning of the Judeo-Christian God. He was slightly more circumspect. He thought you could not give up God without giving up the entire moral underpinning of the Judea-Christian worldview. In other words, Nietzsche understood that when and if we finally give up on God all that is left is the will to power and the ennui of nihilism. Will to power leads to the political reality of totalitarianism. (scholars have drawn a direct line between will to power and Nazi Germany). And ennui leads to the question is my life worth living (the atheist philosopher Camus drew a direct line between annui and suicide when he postulated that the only serious question left to consider if there is no God is whether life has any meaning or purpose). These are dangerous ideas and Nietzsche knew it “. Christ is indeed incompatible with the ideas of Nietzsche eternal reoccurrence. You choose him and his forgiveness or you choose to live in a perpetual time warp of your own meaningless search for perfection. The Christian tradition in the new testament holds that Gods love in Christ perfects us through the forgiveness of the cross. There is no need to become perfect. there is only the need to accept forgiveness and live the good as Christ encourages you to live. It leads to God not endless loops. These Hollywood stories don’t represent the best of secular humanism because they draw on the “good” that has already been revealed to us in the framework of the Judaeo-Christian tradition. The characters within are thirsty to discover the God who is the origin of the good they seek to become. Well that’s Christ. If people would read him carefully, he is wiser than Nietzsche and all of us and provides much more hope

How did I miss this treasure in December 2019?