It was last summer, during a hot spell, and we were driving from Haleyville to Double Springs, Ala., on a county two-lane — both windows down, going 50 miles per hour. They call it “two-fifty air conditioning” down there.

We had the Elvis Presley Sun Sessions on — just loud enough to hear over the rush of thick air. The songs were recorded in 1954 and ’55 in Memphis, Tenn., a few hours to the northwest. We were driving past tumbledown barns and weathered frame homesteads and the overgrown drive-in movie theatre on State Route 195. Through the woods, the light was gold across the hills of Alabama. There was an occasional soybean field, or maybe sweet potatoes. Some cattle in the long shadows of the valleys.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

This was Winston County, population 24,000, where almost 90 percent of people voted in favour of Donald Trump in last November’s presidential election. No other county with more than 2,500 voters recorded a higher level of support. For that reason alone, I had not expected to like the place.

But when we pulled into Double Springs, I said to Nigel Dickson, who was driving and who took the photographs for this article, that maybe that was the best car ride I’d ever had in my life. Up there anyway.

Canadians think too much about the United States at the best of times, and last summer was a long way from best. We were in Winston County a couple of weeks before the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Va., but even then the news out of Washington was sad. At least, that was its effect on me. I’d sit in a $48-a-night motel room, just up from the Piggly Wiggly supermarket in Haleyville, watching Fox News and drinking warm Corona. If you feel like a good cry, I can recommend the combination.

When I was a kid, the news of the U.S.A. was happy. Oh, I know, it was a little more complicated and a lot less cheery than that. But I was a kid. A white, middle-class kid. What did I know? And what I picked up when we went on family road trips to Florida or to the Buffalo Zoo was a buzz of something that felt the way I felt when I saw a red Frisbee float across a blue sky for the first time. So maybe it’s just an age thing. Maybe in the way children were once attuned to American happiness, older visitors to North Alabama are now more likely to weep in their motel rooms with their televisions on. Fox News can do that to you. So can life. You get some water under the bridge. You get your heart broken. You get to know sadness when you see it.

The profanity-laced outburst of short-lived White House communications director Anthony Scaramucci fed the news cycle during our time in Winston County. With each passing scandal, the sheer awfulness of President Donald Trump was coming into sharper focus. Disheartened Canadians couldn’t help but wonder about the people who voted for so obvious a con man. Who are they? What were they thinking? Did they still support the new president? These seemed like good questions, journalistically speaking. Apparently, we weren’t the first to ask.

“Some reporters from the U.K. showed up a while back. And a television crew from . . . where was it?”

The speaker was J.T. He was putting the question to another singer whose name I never got. This was during karaoke night at the Goldiggers Bar and Grill, on our first night in Winston County.

J.T.’s got a good, low, rough-and-tumble southern voice, and he’s got a lot of jokes, some about hillbillies, most of which you wouldn’t repeat in mixed company — meaning company that isn’t white, middle-aged, male, probably Republican and at least nominally heterosexual.

Goldiggers is a fair size. Double Springs isn’t. We passed by the town a few times before we realized that we’d already driven through it.

The town centre of Double Springs is notable for a Civil War memorial. It portrays a soldier wearing elements of both a Union and Confederate uniform. That’s because Winston County was as much against one side as the other in those days. It actually considered becoming the Free State of Winston in the early years of the war. And this is something that should be clear from the start: people from Winston County tend to be contrarian, and have been for a long time.

All the same, this is the South, and the Civil War is always in the background, like the buzzing of cicadas in the still summer dusk. But the prevailing memory of the Civil War in Winston County is not the story of a brave soldier or gallant general. It’s the story — still told in dramatizations by Carla Waldrep, the librarian in Haleyville — of an extremely persistent woman.

Like a lot of people in 1860s Winston County, Jenny Johnson didn’t want anything to do with a war that, as far as she was concerned, was between rich people from the North and rich people from the South. In those days, neutrality was a dangerous position to take. Confederate guerrillas — precursors, approximately, of today’s alt-right thugs — would hunt down shirkers, and when they found them would often torture and execute them. They did this to Jenny Johnson’s husband and oldest son, and she vowed to kill every raider who had anything to do with it.

Johnson lived out in the woods — somewhere in the thick interior of what is now the 73,340 hectares of the Bankhead National Forest. She knew about healing plants and secret potions, and to this day people swear they see her ghost sometimes on the side of the road when the moon is just so. The story of Jenny Johnson is that she lived to be very old. And together with her sons and grandsons, she got all but one of those raiders. One by one.

Jenny Johnson and the anger her Civil War story embodied were a surprise for me. Other things about Winston County were not. People are not shy about making it clear that it wasn’t an accident Trump did as well as he did here. “I just want the government out of my life and out of my pocket,” one man said to me. Someone will say, “If Obamacare had a different name, it would be more popular.” And someone else will tell you, plain as day, “If the president doesn’t deal with Muslims, there will be some killing.” There are people who will just point-blank tell you they don’t want to pay for health insurance for black folks who live on food stamps and don’t do a lick of work and never will. The same people will usually add that there are good-for-nothing whites, too. But you heard them right the first time.

Double Springs is known for the beautiful Smith Lake, deep and clean and created when Alabama Power finished the Lewis Smith Dam on the Sipsey fork of the Black Warrior River. The dam was completed in 1961, and that’s a year you should bear in mind: it pretty much marks the tail end of the period on which American political nostalgia firmly rests. The victory of the Second World War defined how Americans came to expect wars to end — with a parade and a booming economy, with renewed energy and national purpose. The afterglow of the war was a period of prosperity and bustling growth that came to define what many Americans expected America to always be. When Americans say they want to make their country great again, what they’re saying is that they prefer things the way they were before. In the South, this mostly means the way things were before the civil rights movement.

Not that the struggle had much effect on day-to-day life in Winston County. The black population has always been a drop in a big, white bucket. Zeee-roh is the local pronunciation.

Before the Civil War and emancipation, settlers moved west to Alabama, many from Georgia, because property was cheap and taxes were low. Lower than almost anywhere. And this fact holds true to this day. Property taxes in Alabama are one-third the national average. There’s not much of a safety net in Winston County.

Farms in Winston County tended to be small family operations. There was little money for slaves, nor were most of the farms big enough to justify feeding, clothing and sheltering them. People claim that because there were few slaves then, there are almost no black people now, and that’s why the emergence of the civil rights movement had no obvious impact on Winston County. Except that it ended up changing everything.

Capitalizing on the fallout from civil rights, Richard Nixon fashioned his racially tinged “southern strategy” in the 1968 presidential election and won disgruntled white Democrats over to the Republican Party. From Nixon’s strategy, Reagan fashioned his. And on America went — through the rise of corporatism, the Christian right, Fox News, Karl Rove and the Koch brothers, all the way to Goldiggers Bar on karaoke night. This was the triumph of the right. One year ago, nine out of 10 voters in Winston County did exactly the opposite of what the New York Times, the Washington Post, The New Yorker, a certain former president and a red-carpet load of Hollywood A-listers told them they should do. That’s just kind of how they are.

The Lakeshore Inn and Marina complex at Smith Lake occupies what used to be land overgrown with swallowwort and stranglers. The valley where Jet Skis and bass boats today ply the deep, clean water was once a hollow, a densely uncharted scrabble of creeks and trails. It used to be the kind of place that people in Winston County call “real backwoods” — a term that describes land thick with honeysuckle and trumpet creeper, but also, in a less botanical sense, a certain rusticity. “Oh, there’s some real Jerry Springer stuff goes on around here,” a bartender at the Lakeshore told us, referring to the seamy talk-show host. “When you cross the county line, you go back 50 years.”

Lonnie Abbott looks backwoods. It’s fair to say. His wife is a descendant of Jenny Johnson, but it’s Lonnie who can tell if a woman’s pregnant, even before she knows it. This talent doesn’t help much with what he does for cash, which is sometimes mowing lawns.

He lives on the back side of a hill, the front side of which has some interesting junk on it. This is out toward Addison. I couldn’t tell if the junk was for sale or if it had just been unloaded there 30 years ago. When we stopped to ask, Lonnie’s son went off to wake Lonnie up, and after a few minutes Lonnie appeared. He looked more like he’d been roused from hibernation than an afternoon nap. Which is probably why people call him Grizzly.

We talked bottle caps and jackknives for a while. Then I asked what Lonnie thought of Trump. He gave his shirt a thoughtful flick. “I didn’t think we’d elect no Russian president,” he said.

“Backwoods” isn’t an insult in North Alabama. It’s a statement of fact. There are backwoods homes. There’s backwoods cooking. And people. A few churches in Winston County were described to me as “real backwoods” — offshoots of offshoots of not-very-mainstream-to-begin-with strains of evangelical fundamentalism. In Winston County, there is a long tradition of expressing doctrinal differences of opinion by starting another branch of whatever Methodist or Baptist or Church of Christ denomination you started out in. And that’s something else you need to know about Winston County. People tend to see things differently than the next person.

Goldiggers Bar and Grill is part of the Lakeshore Marina complex, although historians might dispute the choice of “Goldiggers” as the name for any establishment in this county. Not a lot of gold was involved in the county’s settlement — which is something you can guess when you drive around. The median household income is US$33,000, and the poverty rate, 19 percent, is six percentage points higher than the national rate. Lots of businesses — lunch counters and shoe stores and butcher shops like small towns always used to have — are boarded up.

Walking along the main street of Haleyville one weekday morning, I noticed that you can actually hear crickets in the bricks of some of the empty storefronts.

Some business owners are making a go of it. And some, more than a go. The menu at Chef Troy’s Talk of the Town Restaurant, located in the tiny community of Houston, is four times bigger than what it was when the place opened eight years ago. Sometimes in the summer, Chef Troy Hill will do $25,000 a week in business, and that’s not counting catering. The economy’s been sluggish recently, he said (meaning the last three years), but he thinks that things will pick up when people start to realize they can’t stay at home and collect welfare. “People here in the United States have been getting too many things given to them,” he said. He thinks that’s going to change under Trump.

Toby and Judy Sherrill, along with most of their family, run the old Dixie Theatre and the adjacent Dixie Den restaurant on the main street of Haleyville. Like Chef Troy, the Sherrills are hard-working and community-minded, and in response to a question about Trump, Toby will tell you that he’s optimistic about the future. It’s not clear how much credit Trump can take for this. It could just be that to be in business in Winston County, you have to be an optimist.

Our time in Winston County began with someone telling us to report to the sheriff in Double Springs before we got ourselves shot. This wasn’t a threat. But the point was made: strangers poking around Winston County might not mix well with the second amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

That was our introduction. Our time in Winston County ended one week later, on the front porch of a mobile home in the woods off County Road 68, when the summer night was thick as velvet and alive with the sounds of crickets and frogs, and the apple and cranberry wine was being poured round by a man who made knives, some of them as big as my forearm. We were talking, the way people always used to talk on summer porches before there was television.

There was the Haleyville librarian, Carla Waldrep (“Miss Carla,” as she’s known locally); her father, James Crane, the knife-maker (“Ain’t nothing for me to trade a knife for a gun — or maybe two knives for a good gun”); Carla’s mother, Margaret, who was born “oh, three mile away” into a family of 14 children; and Carla’s husband, Chuck, who’s a long-haul truck driver and was just in from Tennessee that afternoon. “We never imagined we’d be in the state we are in now,” Miss Carla observed about American politics. “We thought they would work together for the betterment of the people.” It was hard to know if Miss Carla was being critical of the president or the forces aligned against him. Or both. This was not an uncommon ambiguity in Winston County conversation.

Politics aside, if you ever get a chance to sit on a porch in the woods of North Alabama in the middle of summer, with people as good as Miss Carla and her family, I recommend you take it. Even if you remember everything that’s wrong with the place — and its overwhelming support for Trump most neatly conveys that wrongness for me — you’re going to fall a bit in love with it. So fair warning.

But also be warned that not everyone is as open and hospitable as Miss Carla and her kin. Not that the people we met in Winston County were unfriendly. It’s just that, to varying degrees of intensity, suspicion is the starting point of any acquaintance an outsider has with somebody who’s from there. And pretty much everybody who is there is from there.

Wanda Kay Curtis, who runs a Christian-themed vintage and collectibles store called Restored by Grace on Haleyville Road in Double Springs, didn’t exactly say no when I asked if we could attend the church she goes to. Her husband’s the preacher. I had the sense that their family made up most of the congregation. But she didn’t exactly say yes, either. Wanda said her church was probably too backwoods for us. And left it at that.

An expression of a fierce, withholding neutrality is something that feels very American to me. It might only last for a few seconds, but it’s not what I’m used to. Canadians generally feel the need to at least pretend to welcome strangers they encounter. Not so Winston County.

“Y’all not from around here” was the most common conversation opener we encountered. This was always stated in a way that was more assertion than question. We were noticed everywhere we went. By the teenager behind the counter at a fast-food joint called Jack’s who could not, for the life of her, understand Nigel’s English accent. (He was trying to say “cheeseburger.”) By the waitress at the barbecue place on 195 who’d just got back from a church bus tour to see a life-size replica of Noah’s ark in Kentucky. And by everybody in the Galley Restaurant every time we sat down for breakfast every morning.

A few good old boys always patronized the Galley at that time of day — guys accustomed to getting up early, but now with not much to do once they did. They make a good breakfast at the Galley: biscuits, sausage, fried eggs, grits. Fox News was usually on the TV, and coffee was in the pot.

Red Hubbard was our server on several occasions. She has a spark that makes you think she could be running some enormous corporation somewhere had she been dealt a better hand. We were in the Galley regularly, and it was Red (pronounced Ray-yed) who told us, cheerfully and with the forthright tone of someone stating an obvious fact, that we kind of stood out.

But suspicion tended to evaporate pretty quickly. By the time we stopped in to say goodbye to Wanda Kay Curtis six days after we first met her, she was giving us knitted pot holders for our wives and inspirational CDs to listen to on the drive back home.

Readers of a certain vintage might have brushed up against Winston County in January 1994, when it was mentioned in a widely read obituary. Pat Buttram had died.

Buttram was an actor famous for playing Gene Autry’s sidekick in the singing cowboy’s TV show and movies from the 1950s. Later in his career, Buttram played Mr. Haney, the porkpie hat-wearing con artist on the 1960s sitcom Green Acres. The humour of Green Acres was adolescent. By happy coincidence, that’s what I was in the 1960s. A star-struck 12-year-old part of me is amazed I’ve spoken to somebody who actually knew Mr. Haney.

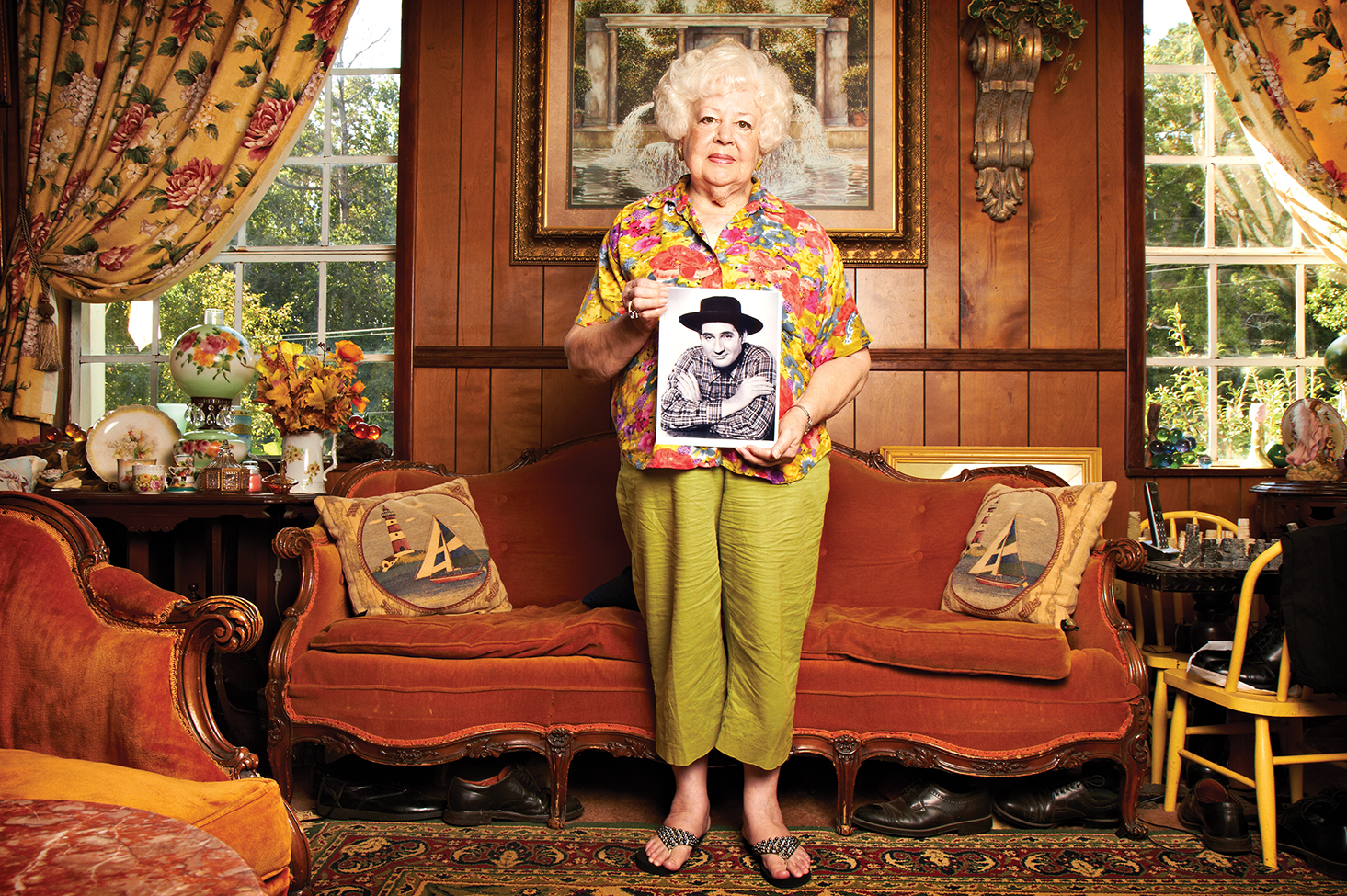

Buttram was born and raised in Winston County. He’s buried in the Methodist cemetery on County Road 93 northwest of Double Springs. And if you remember Mr. Haney, you might be interested to know that the elongated twang of his voice wasn’t acting. The high-pitched drawl that sounded like air brakes on an 18-wheeler was actually how Buttram talked — at least that’s what Shirley Sudduth told me. Shirley knew Buttram before he became famous, and the evidence of her lifelong interest in his career is clear enough to any visitor she cordially receives.

Shirley helps organize the annual Pat Buttram Days, a local fundraiser every fall that pretty much everybody in Winston County enjoys so long as it doesn’t conflict with football. The house she shares with her husband, Coy, is a little on the cluttered side, although Shirley prefers the word “collector” to “hoarder.” It’s partly a Pat Buttram museum and partly a home for Shirley’s I Love Lucy memorabilia. She also paints lighthouses for people who are terminally ill to remind them of the beacon of Christ.

Shirley has buried four of her five children. We were standing in a narrow hallway between two of her full-to-capacity bookshelves when Shirley told me about the night the angel of the Lord visited her daughter, and her daughter convinced the angel to ask God to let her live long enough to raise her child. Which is what happened. Years later, when the angel returned and her daughter died, a white feather drifted down from the sky, which Shirley takes as a sign that her daughter is happy and in heaven.

This was the second time in three days that someone I’d known for less than half an hour told me about a direct communication with God. After I’d been there for a while, I didn’t doubt these testimonials — at least, I didn’t doubt the conviction with which they were offered. Because this is something that you have to take on board about Winston County, and I mean really take on board.

According to 2010 figures from the Association of Religious Data Archives, almost 15,000 people (nearly two-thirds of the population) belong to one of the county’s 75 officially recognized congregations, 62 of which are Evangelical Protestant. And that is the key demographic of Winston County: while there may be a shortage of people with university educations (11.4 percent of the population), a shortage of African-Americans (0.8 percent) and a shortage of Muslims (practically zeee-roh), there is no shortage of old-time Christian believers.

In Winston County alone, you can go to the Adair Chapel or the Antioch Baptist or the Arley Church of Christ or the Arley United Methodist or the Ashridge United Methodist, and that’s just some of the A’s in a directory of the county’s churches. And if you do attend one of those churches, you’re not going because you want to show off your new shoes. You’re going because you believe. You’re there to raise your hands and witness the coming of the Lord. You’re there to be saved. Do not underestimate this. In Winston County, the spirit of the Lord is as present as the weather is. And the weather is like walking into a sauna.

Winston County is home to more than a few impressively large churches, with ample parking and comfortable adjunct residences for the pastor’s family. But there are also lots of places in the woods that nobody knows much about. These bring the number of churches in the county up to something more like 100, each of them sharing the conviction that their particular interpretation of the Word is right and everybody else’s isn’t. This is something else worth bearing in mind: if you argue religion (or for that matter, politics or football) with someone from Winston County, there is every possibility that you are arguing with someone who has been raised to believe that any facts you might mention are not facts at all.

The national pastime of Winston County is sizing people up. So why didn’t they size up the fakery of Donald Trump?

During our stay, there were times when it felt like we had, in fact, gone back more than 50 years.

And it wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. One Sunday morning, Nigel and I showed up unannounced at the old Corinth Church, a plain wooden one-room building with 14 pews and no electric lights, situated in the woods of the Bankhead National Forest. We introduced ourselves to Pastor Bill Wilson and his wife, Bonnie, and at the beginning of the service, just before prayers for family or friends or fellow church members who were ill, of which there seemed to be quite a few, Pastor Wilson introduced us to the 30-or-so members of the congregation. There was no pulpit, no organ, no piano. No anything except unpainted wooden walls and the wobbly voices of God-fearing people singing the good old hymns the way they’ve been sung for generations. There was something comforting about it, Nigel said.

The great Olympic runner Jesse Owens, who is as iconic a black hero as they come, was born in Lawrence County, immediately north of this almost exclusively white, high school-educated, socially conservative Trump stronghold. A lawyer named Jerry Jackson, who is white, mentioned this to me. The emotions stirred by pronouncing Owens’ name brought Mr. Jerry, as he’s better known, to tears. Something else that doesn’t square with the stereotypes: a distinguished federal judge responsible for landmark civil rights decisions in the 1950s and ’60s was from Haleyville. Frank M. Johnson, who was (needless to say) white, was so great a jurist that George Wallace, Alabama’s segregationist governor for 16 years, off and on, and a four-time candidate for president, called him an “integrating, scalliwagging, carpet-bagging liar.”

I’ll grant you the mainstream of public opinion in Winston County. It’s pretty obvious by the way the county voted. But there are unexpected back eddies. “I’ll tell you one thing,” somebody who made me promise not to name him for fear he’d be “run out of town” said, “but I can’t stand that sonofabitch we have in the White House now.”

And curiously, at a time when everyone else in the world couldn’t stop talking about Donald Trump, nobody I spoke to in Haleyville or Double Springs or Addison wanted to pursue the subject with much enthusiasm.

You can let what Shirley and Coy Sudduth had to say about politics stand as the general view (even people introduced to me as big fans of the president didn’t contradict them). They said that they didn’t vote for Trump as such. “We voted for change,” Shirley said. And that pretty much sums it up. And they think the economy is picking up. At least that’s what they hear. Then, the subject is dropped.

“Oh, I’m almost at the point of crying about the loss of small-town America,” Mr. Jerry said to us. We had learned about Mr. Jerry from Miss Carla. I asked her if she knew anyone in the area with whom I could speak about local history. Miss Carla exchanged an, oh-is-there-ever-an-obvious-answer-to-that-question look with the assistant librarian.

When Mr. Jerry laments the waning of small towns in general, he’s alluding to the economic realities of Winston County in particular. The population of the county has been slowly but steadily declining over the past two decades. The minimum wage in Alabama is the federal minimum, $7.25 an hour, and as a result a lot of people must hold down two jobs just to get by, let alone engage in discretionary spending of much benefit to the local economy. You’ll see “Now Hiring” signs out front of mobile home plants and mattress factories and lumber yards and chicken packagers — all of which were once much bigger players in Winston County than they are now. But the work is hard, and the money’s no good.

An experienced litigator, Mr. Jerry has a knack for the dramatic pause. “The reason Winston County is the way it is,” he said, “is because it’s independent as hell.”

The idea of the county seceding from the seceding states in the Civil War gave birth to the phrase, “The Free State of Winston County,” and it’s a description Winston County has always been happy to have. It takes pride in being a little north of the South, and a little south of the North.

When Mr. Jerry said “independent as hell,” he gave the expression a certain emphatic weight. Try to imagine how much it changes your perception of things if you generally assume that everybody outside your immediate circle of family and church is going to disagree with you. The majority is the last thing people in Winston County ever are. They were probably as surprised as anyone when they woke up on Nov. 9, 2016, and learned that the candidate they had supported had been favoured by almost 63 million other Americans, and that Donald Trump, of all people, was America’s president-elect.

When a loved one dies, the fact of that death stays with you for a long time. It doesn’t stay stormy, of course. You can’t cry all the time. But even on an almost-perfect day, there’s a cloud on the horizon. It never goes away.

After the service at the old Corinth Church, Nigel and I stood in the doorway and chatted with anyone who wanted to talk about Winston County. It was there that we learned about Decoration Sunday, when the congregation gathers after worship to maintain and decorate the graves in the churchyard and to remember loved ones who are gone.

As the folks told us how the women would set up a trestle table for the ham and sweet potatoes and poke salad and biscuits and lemonade, and how the men would sometimes drift into the woods for a belt or two of wildcat whiskey, I thought about the sadness I’d felt sitting in my motel room, watching Fox News. That’s how it was: a sadness that I sometimes almost forgot, but then, at strange, unpredictable moments, remembered.

I wish I could fully explain Winston County and its support of Donald Trump to you, but I can’t. There are too many contradictions. Nor am I going to suggest that Winston County represents anything other than itself, because it doesn’t. But I will tell you this: we went from arranged meetings to random encounters, from requests to officials to conversations with strangers, from loud bars to empty highway barbecue joints. We put on some nice miles. After a while, I started to notice that something we were not encountering — not there, you understand, not in the core — was anything that could be called triumphal. They’d gotten their boy in. And about as enthusiastic as anyone seemed to be was: we’ll wait and see.

What puzzled me about Winston County was not so much that it voted the way it did. People here have voted Republican forever — at least in the recent forever. What I couldn’t figure out was how they could vote for someone who’s so obviously a fraud. The national pastime of the Free State of Winston County is sizing people up. So why didn’t they size up the fakery of Donald Trump? That’s what I wondered while I was there. That’s what made me sad. And the only guess I could make was that they sized him up pretty well. Donald Trump was nothing to these people. Nothing they had to be against.

This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of The Observer with the title “Trump country.”

Nigel Dickson is a photographer based in Port Hope, Ont.