AI (artificial intelligence) has had so many booms and busts in the seven decades since it came into being that it has its own jargon to describe them.

An “AI winter” refers to the periods when progress in the field stalled or didn’t live up to expectations and financial support dried up. The most recent winter lasted from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. During that time, the term “artificial intelligence” became such a grant-killer that AI scientists had to find other ways to describe their research, calling it “machine learning” or “informatics” instead.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Today, we are undeniably in the midst of an AI summer, and it’s by far the hottest in history. By every measure — research and applications, investment and commercialization, hope, fear and hype — AI has reached new heights.

This time, the AI boom is real, grounded in scientific advances that have led to better algorithms and big gains in the two essential ingredients: data and computing power. Add to this recipe the economic incentives driving people to speed up AI development and adoption, the possibility of immense profits, plus the lack of guardrails keeping it in check, and this AI summer appears unstoppable.

Many people, including some of the greatest innovators of the 21st century, are celebrating AI’s rise as a triumph of raw curiosity, relentless optimism and scientific progress. They are embracing its potential to streamline our lives, address problems from the mundane to the monumental and augment human potential.

Bill Gates, not particularly known for hyperbole, wrote in an annual reflection on his blog in December: “Artificial intelligence is about to accelerate the rate of new discoveries at a pace we’ve never seen before,” citing science, health and education as major areas of impact.

Others see AI as the scary technological embodiment of naked ambition, greed and hubris, a runaway experiment of the mantra “move fast and break things” espoused by Silicon Valley elites. AI has the potential to disrupt labour markets and democracy, pulling apart the very fabric of society. If superintelligence is eventually achieved, some fear it could bring about humanity’s downfall.

More on Broadview:

Even the most prominent AI researchers in the world, including the University of Toronto’s Geoffrey Hinton, one of the “godfathers of AI,” are warning about unrestricted development of the technology. Hinton and many other experts signed an open letter published in March 2023 calling for a pause on large-scale AI experiments, citing the possibility of “profound risks to society and humanity.” Could this be the biggest ethical issue humanity has ever faced?

Policymakers worldwide are grappling with how to govern AI and when to act. What’s the right balance between regulating risks and nurturing innovation? How can we protect personal privacy and ensure AI systems are safe and fair? How do we make sure AI operates according to a set of ethics we can live with when human values differ so greatly across people and cultures?

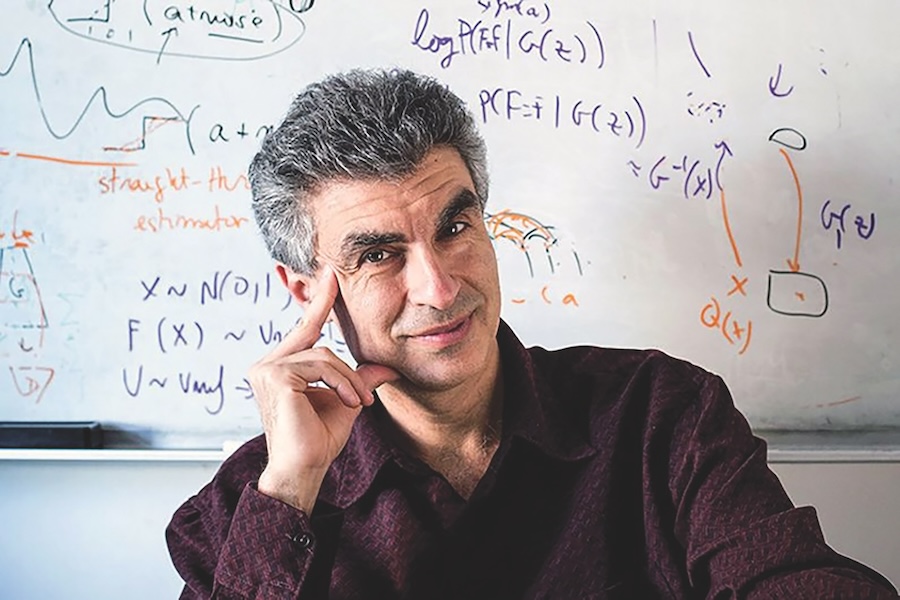

Philippe Beaudoin has seen boom and bust cycles in AI before. He has been an AI research scientist and entrepreneur for a few decades and co-founded Element AI, a significant force in the Canadian tech sector that aimed to put AI research and software in the hands of companies worldwide. As he talks about the technology’s potential, his excitement is palpable, even over Zoom. But he is also troubled by its evolution. After all, even AI makers cannot fully explain how these systems work.

He says we’re at a crossroads. “There’s a big decision we must make as a society exploring this. We can spend more time twiddling with the systems to try to make them better, or we can spend more time probing the systems we have [in order] to understand better how they work,” he says. “We have that choice to make now, and different people are pushing in different directions.”

***

You could say that this critical juncture in the history of our species began on Nov. 30, 2022, when OpenAI launched ChatGPT. That was the day the world could finally play with a sophisticated AI chatbot and experience it anywhere from the classroom to the boardroom.

But there’s another date in the remarkable story of AI that historians will probably point to as well: Sept. 30, 2012. That was the day AlexNet, a neural network developed by two graduate students at the University of Toronto, won a major international AI competition, the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. The students — Alex Krizhevsky and Ilya Sutskever — were training with Hinton, one of the pioneers of deep learning, which is an approach to building intelligent machines inspired by the human brain.

ImageNet is a curated dataset of images scraped from the internet, then categorized and labelled by humans. It’s about 15 million digital photographs, sorted into 20,000 categories like “teapot” or “teddy bear.” Fei-Fei Li, a computer scientist sometimes referred to as the “godmother of AI,” dreamed up ImageNet in 2006. At the time, she was a young professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign looking for a way to advance the field of visual object recognition. In the ImageNet contest, AI researchers competed to teach machines to recognize everyday objects — a formidable challenge at the time.

On that day in 2012, AlexNet trounced the field and won the ImageNet challenge, proving that deep learning could solve problems with real-world applications. “It was like a tipping point,” says Beaudoin. “The way we do AI today changed in 2012.”

In the decade following AlexNet, AI underwent explosive growth. A lot of it happened inside tech companies like Google, Microsoft, Meta and OpenAI. That means it was hidden from public view. Machines learned to make predictions better and faster. They also learned to generate content; that’s where the term “generative AI” comes from. Instead of simply learning to recognize a teapot or a teddy bear, machines began to generate text or images about them on command.

This led to ChatGPT and similar conversational AIs like Google’s Gemini, allowing the world to use generative AI on smartphones or desktops. “What happened last year was this realization that you can make these systems available to people through a chat interface, scale it up so millions of users can use it, deploy it and then make it available to everybody for free,” says Graham Taylor, an AI researcher at the University of Guelph in Ontario.

In other words, the AI moment we’ve lived through in the past year — replete with product launches, an attempted corporate coup over how to develop the technology quickly yet responsibly, and increasingly intense policy debates — is more of a sociological revolution than a technical one.

That’s not to suggest intelligent machines won’t get more powerful and pervasive. They will. After all, the main ingredients — algorithms, data and computing power — are still multiplying. AI systems are already learning by using multiple types of data — text, images, audio, video, music and more — like humans use sight, sound, touch, smell and taste to experience the world. On the societal front, AI is being integrated into more products and services, especially in sectors that touch our daily lives like healthcare, banking, transportation and government. “I’m convinced these ChatGPT-like systems will be the core of every software product we use,” says Beaudoin.

***

Everyone has an opinion about the future AI will create. Graham Taylor, for one. He specializes in deep learning, which uses mathematical principles to simulate brain-like networks of neurons that gradually learn from examples how to recognize objects or understand speech.

In his research lab in Guelph, he works on enhancing deep learning and applying it to urgent global challenges, leaning into AI’s ability to analyze vast datasets at speeds and scales impossible for humans. One of his projects is focused on using AI to catalogue the world’s biodiversity; another aims to use AI to model how climate change will impact life on Earth.

But Taylor is not blind to the potential misuses of the technology, especially as it hurtles forward unchecked. As co-director of the university’s Centre for Advancing Responsible and Ethical Artificial Intelligence and a member of the Expert Group on AI Futures run by the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), he is dedicated to equipping students and policymakers with the knowledge and tools they need to manage AI risks and avoid future harms.

At the moment, he worries about AI’s ability to impersonate anyone — and our inability to separate digital fact from fiction.

Want to read more from Broadview? Consider subscribing to one of our newsletters.

Over the past couple of years, thanks to the widespread availability of new tools powered by generative AI, just about anyone can make deepfakes in minutes on their own computer. And not just fake photos of, say, Pope Francis or Taylor Swift. But also phony audio and video. Some people in New Hampshire received robocalls just before the state’s primary election last January encouraging citizens not to vote. The caller sounded like U.S. President Joe Biden.

Around the dinner table with his wife and two children, Taylor recently discussed establishing a family password — a secret, agreed-upon cue to verify their identity. An “abracadabra” for AI.

The password idea was promoted recently in a Substack newsletter by Ethan Mollick, a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Mollick, who studies AI and its impact on work and education, wrote that “the information landscape post-2023 will never be the same as it was before. I don’t think most people are ready for what that means for privacy, security (come up with a secret family password to prove your identity now!) and global politics.”

Taylor admits he’s more of an “immediate threats type of worrier,” so a current concern, because he has aging parents, centres on the possibility of AI impersonators scamming the elderly. His mentor, Geoffrey Hinton, has more long-term, catastrophic worries about AI. (Taylor was one of Hinton’s graduate students, as were AlexNet’s Krizhevsky and Sutskever.)

“The existential risk is what I’m worried about,” Hinton told a crowd last October at the University of Toronto. “The existential risk is that humanity gets wiped out because we’ve developed a better form of intelligence that decides to take control.”

In the language of Silicon Valley, Hinton is a “doomer” or “safetyist.” The opposite is “boomers” or “effective accelerationists” who advocate for the swift development of AI. Hinton admits the uncertainty around exactly how AI will affect us is huge. He doesn’t deny its more imminent and probable threats, but as he told the packed auditorium last October, “I thought [the existential risk] was a long way off…and having philosophers and academics working on it was great. I think it is much more urgent.”

What changed for Hinton is the arrival of the kind of AI that powers ChatGPT and similar large language models. Large language models are deep-learning algorithms typically trained on massive amounts of data. Increasingly, Hinton said, they also learn new tasks far more efficiently than humans even without vast amounts of training data.

On the AI spectrum from doom to boom, there are plenty of other voices. Like Timnit Gebru’s. The research scientist was fired by Google, where she co-led the ethical AI research team, for sounding the alarm on workplace discrimination. She now runs Distributed AI Research Institute, a non-profit research lab dedicated to making sure AI works for everyone.

She takes issue with doomers and their focus on an unknown machine entity destroying the world. That focus detracts from documented harms already perpetuated by AI-backed technologies — and mechanisms to mitigate those harms, she says. The terrifying prospect of human extinction shields corporations from scrutiny on urgent, critical issues like data privacy and AI safety.

“They [legislators] are not talking about labour exploitation. They are not talking about data protection or corporations stealing data,” she said last August on the podcast Reimagining the Internet. “They’re not talking about corporations not putting in enough resources to ensure that these models are safe. They’re not talking about transparency and asking them what data they’re using. That’s not any of the conversations that we’re having.”

Gebru is also outspoken about the limitations and biases of AI technologies that generate and spread misinformation and enable discrimination against women, racialized people and other historically marginalized groups.

The gender biases are blatant. An AI-based recruitment software once used by Amazon infamously discriminated against female applicants. And tools like ChatGPT, trained on internet data that offers a skewed, patriarchal view of the world, tend to reinforce gender norms and stereotypes. When asked by researchers how a CEO dresses, the chatbot listed suits before blouses, dresses and skirts.

And then there’s what the New York University psychology professor and AI expert Gary Marcus calls the “truthiness problem,” a nod to a term coined by late-night talk show host Stephen Colbert. AI chatbots can provide irrational or misleading responses. They also make stuff up. Developers call these occasional errors “hallucinations.” Chat-GPT, for example, has hallucinated biographical details, scientific papers and legal precedents. Such errors could be life-threatening in some sectors, like health care or the military. In other domains, they could seed misinformation or reinforce harmful beliefs.

“Whatever they say sounds authoritative, but it is not always true; as they say in the military, ‘frequently wrong, never in doubt,’” Marcus recently wrote.

Other examples of generative AI harms include data privacy violations, plagiarism, copyright infringement, misinformation, disinformation and harmful content — including deepfakes.

In the face of these enormous challenges, ImageNet’s Fei-Fei Li, a self-described computer scientist turned humanist who also co-directs the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, is far more optimistic. Li stresses AI’s potential to improve health care, turbocharge scientific discovery and help sustain the environment.

In Toronto, she shared the stage with Hinton — she seated, he standing to ease chronic back pain — and argued that the adoption of the technology will be messy but that it can ultimately lead to a better future.

“I don’t want to paint the picture that tomorrow, we’re gonna have all these robots…creating the machine overlords. I really think we need to be careful in this,” she said. “If we’re going that way, I think we have more than a fighting chance because we are a human society. We’re gonna put guardrails; we’re gonna work together.”

***

So who will decide the future of AI? Corporations, government or citizens? Will Hinton’s dire forecast of conflict rule the future? Or will Li’s vision of co-operation between humanity and AI?

A look at the field today suggests it will be Big Tech and that the future of AI will be driven by profits rather than the public interest. In the early 2000s, the majority of AI research was taking place in academia. Today, the private sector dwarfs academic contributions. In 2022, industry produced 32 significant AI models while academia produced only three.

Why such a disparity? Tech companies have the data, computing resources and AI talent to build bigger models. In today’s AI race, in which bigger models mean better performance, industry has the advantage.

“Although these industry investments will benefit consumers, the accompanying research dominance should be a worry for policymakers around the world because it means that public interest alternatives for important AI tools may become increasingly scarce,” warn MIT and Virginia Tech researchers documenting the growing influence of industry in AI research. This dominance also means less research is being done on AI ethics, safety and methods that are less data-hungry.

This power balance isn’t unnoticed — even if it remains unchecked. Governments and other entities worldwide are starting to act to manage AI risks. In March, European Union lawmakers passed the world’s first comprehensive law regulating AI. Global organizations, including the United Nations, G7 and the OECD are developing principles for the ethical use of AI systems. So are some tech companies, such as Google, as well as non-profits and research organizations.

Last October, the White House announced a far-reaching executive order laying down principles for the safe, secure and trustworthy development and use of AI. Under the order, companies like Google and OpenAI must notify the government when developing large language models like GPT-4 and share their safety results. And the Create AI Act, which would finance academics in AI, is winding its way through Congress.

Canada introduced Bill C-27 and the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act in 2022 to govern the responsible design, development and deployment of AI systems. It is still before the House of Commons. In the meantime, in the absence of regulation, the federal government has introduced a voluntary code of conduct for Canadian companies developing and using generative AI systems and announced an AI safety institute to study the technology’s risks.

Yoshua Bengio, a deep-learning pioneer who leads the Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute in Montreal and co-chairs the federal advisory council on AI, has urged the government to fund a billion-dollar public supercomputer capable of running powerful AI models from tech juggernauts like Google, which is essential to understanding the technology and ensuring it’s safe. The Prime Minister answered this call in April with a $2.4-billion package of AI measures, including access to processing power.

Still, some Canadian AI researchers are calling on the government to go much further. Ishtiaque Ahmed, a computer scientist at the University of Toronto and faculty fellow at the Schwartz Reisman Institute for Technology and Society, says government needs to restrict tech companies’ aggressive harvesting of data. As well, he argues that the government needs to educate citizens about the technology so they can protect their privacy and rights. His overall concern is to ensure that AI benefits everyone, especially marginalized communities around the world.

Elsewhere, top AI researchers in the United States like Fei-Fei Li are calling on governments to do more to unlock the power of data for the public good and to make sure the public sector leads in developing responsible AI. That means building public datasets, expanding national computing platforms and making sure top AI talent work in government. “AI isn’t just a bag of clever products. It has tremendous potential to extend our lives, improve our societies and save our planet,” Li and Stanford colleague John W. Etchemendy wrote in an op-ed late last year.

***

For as long as humans have imagined intelligent machines, people have grappled with how to ensure the machines’ goals don’t conflict with ours, that we are happy with how they behave and that we can trust them to act ethically.

In 1960, the renowned mathematician Norbert Wiener wrote that “we had better be sure that the purpose put into the machine is the purpose which we really desire.” He later wrote: “In the past, a partial and inadequate view of human purpose has been relatively innocuous only because it’s been accompanied by technical limitations.”

Of course, those limitations have evaporated. With the rise of generative AI systems with hundreds of millions of users worldwide, the “human purpose” embedded in those systems matters. Which human values do they respect? Which do they neglect?

Computer scientists call the process of ensuring AI systems reflect human values “alignment.” But it is a slippery goal, not least because all AI systems acquire the values embedded in their training data, desirable or not. Sometimes the information isn’t a quality ingredient.

There is also the matter of whose values? Human values are messy, shaped by culture, religion and other factors. Some are universal, but others conflict. How do we address this pluralism?

Finally, making AI systems that reflect human values is hard. Experts are still trying to figure out whether they can even do it.

“I am frustrated when I see all these regulations that none of them mention how to actually go about coding ethics and safety to AI. They talk about high-level principles that, yes, AI should be aligned with human values, but how do you actually go about doing that?” asks Nisarg Shah, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Toronto and a research lead at the Schwartz Reisman Institute. “We don’t really have a concrete, agreeable answer.”

But he thinks it can be done. One way — and the method widely used today — is to put humans in the loop. Large language models like the one powering ChatGPT are trained with human feedback.

“We put these answers in front of real humans,” who indicate whether an answer is good or not, explains Philippe Beaudoin. “And through that process, we shift the morals, the ethics of the thing a little bit. A human may say, ‘Don’t use that Nazi imagery in your response, even though it is in the training data. We’d like you not to go there.’”

But this method, known as reinforcement learning with human feedback, has its limitations, especially the ability to represent diverse viewpoints. Experts are working on other approaches to value alignment, including ways to enhance public influence on AI and democratize the training process.

Beaudoin favours building AI systems in the open. By making them accessible to a broader range of individuals and communities, we should be able to ensure that the benefits of AI are distributed more evenly across society. Keeping AI systems closed, as most are today, implies that certain groups of people are better than democracy and should dictate the system’s ethics, he says.

Others fear opening up AI will make the systems vulnerable to misuse by bad actors who want to develop biological weapons or find new ways to monitor and oppress their citizens.

Some researchers, like Shah, think we can go further than mere alignment and build AI systems with superhuman moral judgment. These intelligent machines wouldn’t simply mirror human values; they would surpass them.

It’s an idea psychology professor Paul Bloom pondered in a recent article in The New Yorker, in which he asked, “Are we sure we want AIs to be guided by our idea of morality?” Given all the ways our values fall short, maybe we should strive to improve on human values rather than replicate them in machines, he suggested.

In fact, Shah says in some cases we already expect AI systems to perform better than humans and show superior moral judgment. Consider self-driving cars. We accept that human drivers will kill a handful of people in Canada every day. Yet we find even a single death caused by an autonomous vehicle unacceptable and expect the cars to, too.

So how do you build AI with better-than-human moral judgment? According to Shah, the answer lies in the wisdom of crowds. He thinks that if you asked a thousand, a million or a billion people to make a moral judgment, then removed the outliers and looked for commonalities, the crowd’s wisdom would be more moral than an individual’s.

The rub is there isn’t enough data to train AI systems this way, which is why he is working on teaching machines to reason their way to sound moral judgments. He envisions AI systems that rely on human judgment when data is available and on a kind of mathematical reasoning when it isn’t. “If AI systems can use a similar style of reasoning that humans employ, then that can lead them to make decisions that are still aligned with human judgment,” says Shah.

It’s a seductive idea, but Ahmed pushes back on the notion that the value alignment problem can be solved with math. “The history of ethics and morality in computer science has always been debated, but I would say most computer scientists approach this field in a naive way. They’re thinking mathematically, that if we have an equal distribution, then you know, it’s all fair.”

Instead, he says alignment is a social problem that requires a social solution. Yes, part of the answer is fixing the algorithms, but that alone won’t fix the biases embedded in today’s intelligent machines because they aren’t created in a vacuum. They are a reflection of who holds power — mostly the white, western and wealthy.

Power must shift back to communities, especially those that have been adversely impacted by the AI revolution or left out of it altogether. Without such a shift, he says, the world won’t achieve AI for good and for all.

***

Lindsay Borthwick is a journalist in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s June 2024 issue with the title “No Turning Back.”