Q Before joining the Senate, you spent 24 years at the helm of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, which works with women and girls in the justice system. What were your first impressions of your new role? How do you understand your mandate?

A I was ready to quit after the first week, and Murray Sinclair [who joined the Senate seven months earlier] took me aside and said, “If you are feeling a little overwhelmed, you will want to quit.” I said, “Yeah, I do.” You get bombarded with everything. Right away, you are inundated with, “Can you take this call?” There are five hundred million receptions. Who knew? I walked to the store today, and there were three receptions happening on the way. I can see how people can get caught up in that. I’ve had to rein myself back in over many sleepless nights.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

I’ve gone back to the call from the prime minister several times in my mind. He said he was offering this appointment based on my career as an activist. That was the word that stuck in my head: “activism.” So I thought, “Okay, well, let’s go.” My life’s work until now has brought me to this place, and I have 18 years here to try to effect some change.

Q You have been an advocate for women. Which groups of women are suffering most in the prison system?

A My experience at Elizabeth Fry underscored for me the linkages between marginalization, victimization, criminalization and institutionalization. The fastest-growing group in custody is racialized women, particularly Indigenous women. More than one in three women in federal custody is Aboriginal. In Saskatchewan, the number is more like eight or nine out of 10, depending on the day and how people self-identify. The number of South Asian women and African Canadian women [in custody] is also increasing. The number of women with mental health issues is going up. The last time we were able to gather stats, 82 percent of women in prison were there for poverty-related offences — you can’t be jailed for being poor, but you can be charged with things like fraud, for example. Too often, people are criminalized for just trying to solve and negotiate poverty. Research around the world shows that where you have the best substantive equality, you have the lowest crime rates and lowest incarceration rates.

Q How does inequality affect criminalization?

A When we were in our teens, we’d get asked, “Have you ever committed a criminal offence, or have you ever stolen something?” All of the self-report studies show that virtually nobody reaches the age of majority without doing something for which they could be criminalized. We only criminalize certain things when they are done by certain people in certain contexts to other certain people. Women are hyper-responsibilized. If you are victimized, somehow it’s your fault, and if you respond to protect yourself, then the weight of the law will come down very quickly to criminalize you. We are still putting women in jail for using reactive violence [against their abusers]. We see most of the women plead guilty, because the only witnesses to the abuse are their kids, and they are loath to have their kids stand as witnesses.

I had a lawyer very recently say, “Well, women usually use weapons.” A woman may be able to go into hand-to-hand combat with a man, but more likely, she’s going to grab a frying pan, a bottle, a knife. I don’t want to be heard to be saying that I think women should be using violence. But I think that the response is so very different when a woman is in that situation.

Q There was a lot of public outrage last fall over the case of Adam Capay, the young Ojibwa man who spent over four years in solitary confinement in Thunder Bay, Ont. How do you feel about segregation?

A I would argue for no segregation for anybody. Once you’ve seen and experienced how it manufactures not just distress but mental illness, you can’t argue for it. Segregation destroys people. I don’t know how you could ever advocate for someone to be in that situation, even for a short period of time. If the United Nations says 15 days in solitary confinement is torture, what is anything less? It’s cruel and unusual punishment in my view.

Q Are jails useful?

A I started out believing in prisons and believing in the role of punishment. Now, I’m advocating getting rid of jails. I see no benefit anymore. If we took the $211,000 a year it costs to keep a woman in federal custody and invested that in social programs, it would benefit not just that woman but 90 percent of the kids who end up in the care of the state. You have to take into account the human, social and financial costs. One of the first things Nelson Mandela did when he became president [of South Africa] was to free all the women in prison who had children under the age of 12. He said that to jail a woman was to relegate generations to come to subjugation.

We have precedent for doing progressive things. With the Syrian refugee issue, communities banded together and sponsored someone. We could do the same thing with prisoners. We could say that there is a community that wants to take in one woman and her kids. We could get that woman out of jail and her two kids out of child welfare. We could do that.

Q What about the really dangerous offenders?

A Clifford Olson. Paul Bernardo. Robert Pickton. They were men who committed monstrous acts. But before they committed monstrous acts, there were many, many times when there could have been interventions. It really was the unwillingness of the system — whether it’s the police, the Crowns — to actually see the violence these men were committing or to see the women as worthy of being protected. So Olson was attacked in prison and ends up in protective custody. Who is he there with? A guy who had done what Olson ended up doing when he got out. Not to excuse anything he did, but if we don’t understand how we help create the individuals or put people in positions where they are capable of committing monstrous acts, then we don’t take our responsibility. Bernardo? Women had given his identity [to investigators]. The police had his DNA. He just didn’t fit the stereotype of a serial rapist and killer. Pickton was picking up women in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Everybody knew. Why did he get away with it for so long? Because they were seen as disposable women. Col. Russell Williams? All the evidence pointed to him, but no one could believe it was him.

These aren’t the only people who have done monstrous acts, but if that’s who we hold up, then I would be willing to say, “Let’s hire 10 to 20 people who could be humane and keep them confined so that they could never harm someone else.” I’m not saying that they wouldn’t experience that as a prison; I’m prepared to live with that hypocrisy.

Q Are there places that can model systemic reform for us?

A Norway is one country that is often held up. There are pockets of other places where things are done better. But my initial impulse is to say, “Why can’t Canada be that?” I think we have opportunities to do something really different in Canada. We started to lose [our international reputation] over the last decade, but historically we have been seen as progressive human rights defenders. I think we should demand to take that mantle back and really lead the way.

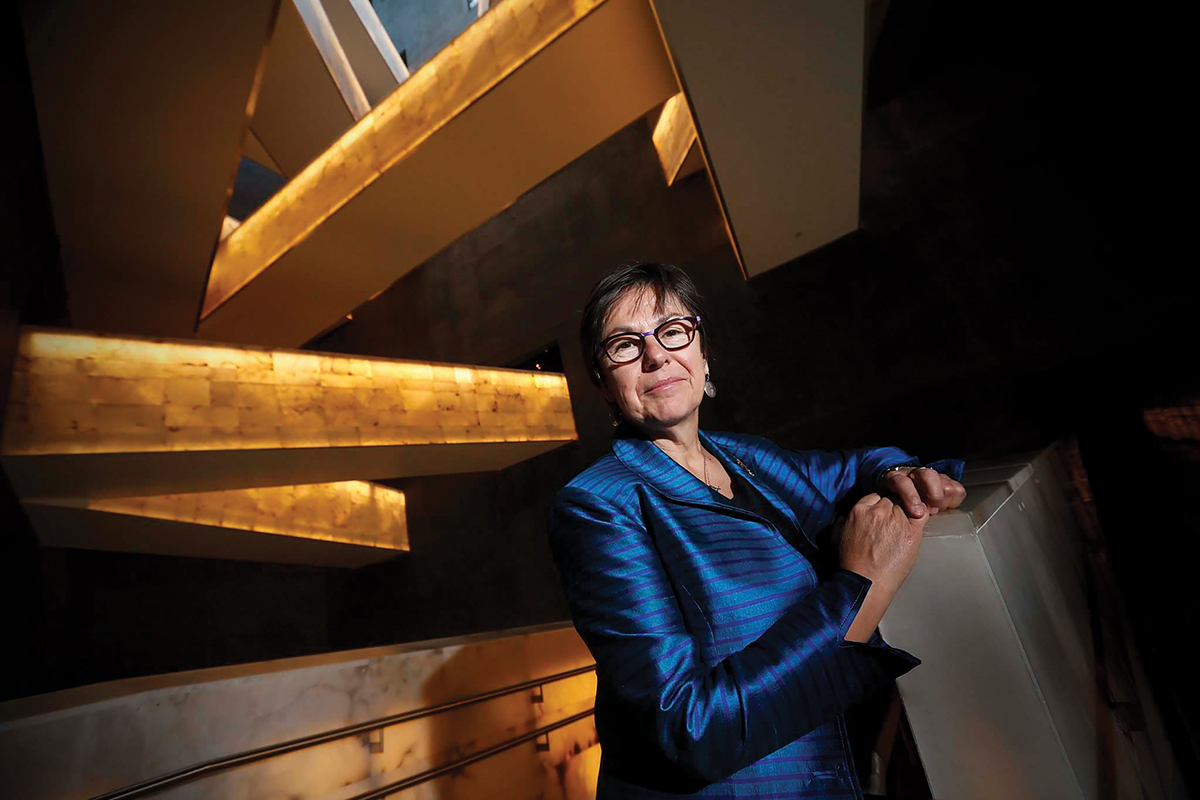

This interview has been condensed and edited. It first appeared in The Observer’s September 2017 issue with the title “Interview with Kim Pate.”