On July 20, 1944, near Lake Matese in Italy, the chaplains of the Canadian 1st Infantry Division held an extraordinary event on a hilltop in the middle of a war zone: a multi-denominational School of Church Membership.

Chaplain H/Capt. Laurence F. Wilmot of the West Nova Scotia Regiment described the event in his diary: “It was a beautiful day for our outdoor school and the discussions and programs went as planned. A grand total of 606 candidates prepared themselves to become active members of the Church of Christ in various denominations while serving in the army in the midst of the chaos of war.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

His colleague, H/Maj. R.C.H. Durnford of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada also wrote about the event: “Marvellous day… Hymns were sung and prayers put up… The classes were divided up along denominational lines. [Church of England and United Church] were the most numerous, about 150 each (or more)…We baptized about 30 boys that day.”

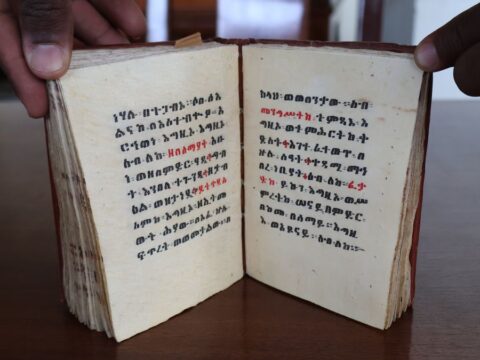

To mark the occasion, every graduate received a pink communicant card to carry with them as a physical reminder of their decision. Four days later, at All Saints’ Anglican Church in Rome, the Bishop of Lichfield confirmed 250 of the school’s candidates.

I first became interested in how faith shaped the lives of soldiers in the Second World War because my paternal grandfather was a Baptist lay preacher who served with the Royal Air Force. Now, as a doctoral student at Durham University, U.K., I’m researching the impact of faith in the Canadian Army from 1939-1945.

The School of Church Membership was much heralded at the time, with newspapers across Canada, including Broadview’s predecessor publication, The United Church Observer, carrying the story. Many publishers also included a table showing the exact number of confirmations achieved per Protestant denomination.

More on Broadview:

- 141 members of this United church went to war. 19 never returned home.

- 30 years ago, a Bosnian imam gave me a great compliment

- Interned for being Japanese, my family found hope thanks to one minister

In August 1944, the men and their chaplains returned to action on the Gothic Line. Not all of them would return. As Wilmot painfully wrote in his diary: “I walked about and obtained the names of 11 or 12 of the dead. Some had in their wallets the pink card they received in July for attendance at the Church Membership School, indicating that they had become communicant members of a denomination.”

If the sight of those pink cards was not reminder enough of the turn of events and the horror of war, the chaplains then had to bury their new brothers-in-Christ, record the hard facts for burial returns and then write home with the news to the families.

On Oct. 26, 1944, the New Glasgow, N.S., newspaper carried the story of a local young man who had recently died in Italy. The article cited a letter sent to the man’s mother by H/Capt. E.W. MacQuarrie, chaplain of the Carleton and York Regiment, 1st Canadian Infantry Division. MacQuarrie wrote: “Personally as his Padre, I had the warmest admiration for him. He always stood for high ideals and only this past summer, when we had a Divisional School of Church Membership, did he come forward to make public affirmation of his Christian principles and faith and, as you must know, received confirmation at the hands of the Bishop of Lichfield in Rome.”

The story of Lake Matese may be fading with time, but I believe those young men’s public proclamations of faith in the mud and blood of the Italian campaign can remind us that love does not surrender to death. The men and women who served in uniform in defiance of evil bear witness to this still.

***

David Macmillan lives in Edinburgh, Scotland, with his wife (who was born in Toronto) and their two daughters.

Great & inspiring story – thank you!