One night in 2017, Chief Michael Recalma had an extraordinary dream. Several of his ancestors appeared to him in their traditional regalia — elaborate button blankets of blue, red and black and woven cedar hats. “They told me, ‘This is what you have to do: you have to start working towards bringing back the pentl’ach language, because people think it’s extinct. And we, as people, are still here. You’re still here.’”

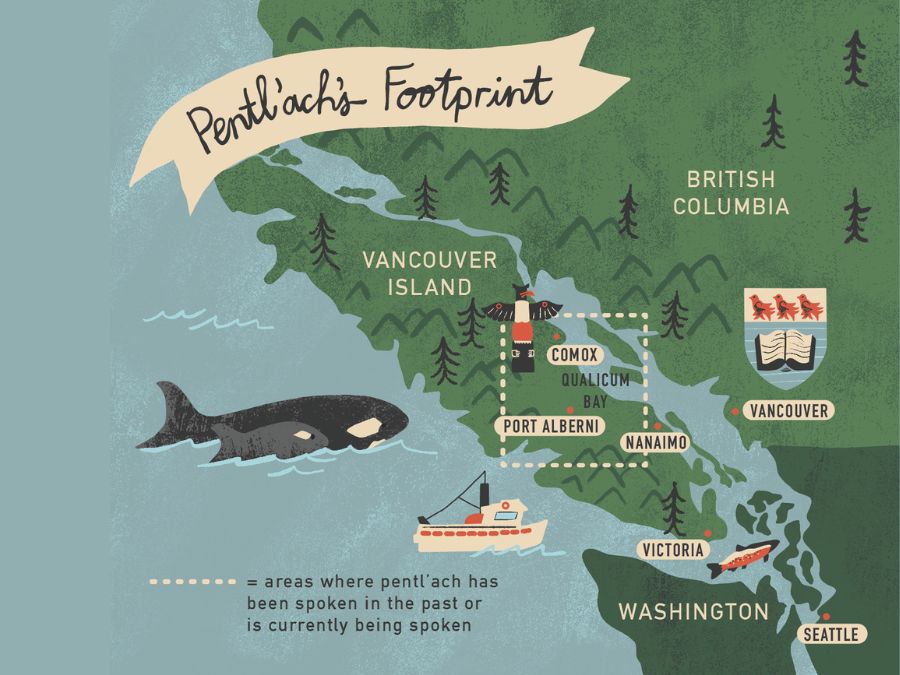

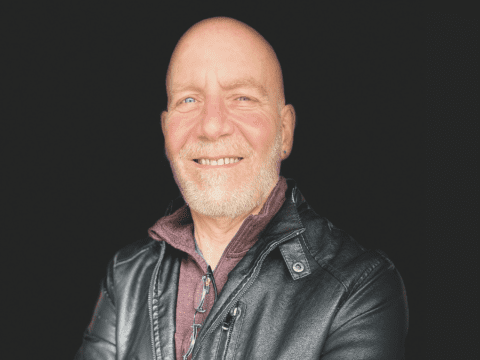

Chief Recalma, whose traditional name is Mugalease (“traditional person”), is the elected leader of the Qualicum First Nation, a Coast Salish community with fewer than 100 members living both within and outside their traditional territories on the central inside coast of Vancouver Island. His ancestral language, pentl’ach (pronounced PUNT-lutch), had been considered extinct since the early 1940s after its last known fluent speaker, Joe Nimnim, died.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Chief Recalma understood immediately that the dream and its message were significant. “The ancestors I saw were the very, very old ancestors. I’ve been told that they were the elders of the elders, because in the dream, they were up here, above,” he gestures skyward. “There was no actual verbal communication, but I knew what they wanted. I knew I had to act, and I had to act soon.”

But how to even begin? To revive an endangered language requires both immense effort and complex strategy, often relying heavily on elders’ knowledge to create learning materials for younger generations. When no living speakers remain, as was the case with pentl’ach, the language is considered to be asleep and the task of awakening it is exponentially more difficult. The community must rely on available documented resources, such as field notes and audio recordings made by missionaries or anthropologists. It’s a labour of love that can take decades, if not generations, of dedicated work.

Once spoken by as many as 6,000 Qualicum and other First Peoples between Comox and Nanaimo, pentl’ach didn’t simply disappear overnight. Like other Indigenous languages of the Pacific Northwest, its slow erosion can be traced back as far as the late 18th century, when European explorers first arrived. They, and the traders and settlers who followed, brought diseases to which Indigenous people had no natural immunization — tuberculosis, measles, influenza and smallpox — wiping out vast numbers of the First Nations’ populations. The smallpox epidemic of 1862 and other diseases killed an estimated 90 percent of pentl’ach speakers.

The assault on Indigenous languages continued as a direct result of colonial policies enshrined in the Indian Act. Indian residential schools, which operated across Canada for more than 150 years and were run by the federal government and churches, played a major role. According to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the schools were “a systematic, government-sponsored attempt to destroy Aboriginal cultures and languages and to assimilate Aboriginal peoples so that they no longer existed as distinct peoples.”

For Indigenous Peoples, awakening a dormant language is essential to the continuation of a unique identity and distinct worldview.

Pentl’ach “is a language of the land; it’s one of the ways that we connect with the world around us, and we’re unable to do that properly if we’re not able to share the words in the language,” says Jessie Recalma, nephew of Chief Recalma. “You have four pillars of understanding who we are as Indigenous people: land, language, people and culture. None of these can effectively exist for us if the other is missing, and the loss of one affects the well-being of the other three. When you’re missing one, you’re missing a part of yourself.”

***

Up until a decade ago, the only known surviving archive of pentl’ach was from the work of pioneering American German anthropologist Franz Boas, who visited the pentl’ach people and documented their words and stories in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Jessie Recalma had acquired copies of the Boas corpus a few years earlier, but the community hadn’t yet been able to put it to practical use in reviving their language, in part because Boas’s German shorthand is so difficult to decipher.

But right around the same time of Chief Recalma’s dream, a serendipitous event took place in the life of another of his nephews, Mathew Andreatta. “Some sort of knowledge in Uncle Mike woke up right at the same time as something woke up in, or presented itself, to me,” says Andreatta.

Tall and lanky with deep brown eyes and a mop of dark curls, Andreatta is often assumed to be Italian, like his father, but he also has Qualicum and Musqueam heritage. His mother — Chief Recalma’s sister — moved away from the territory as a teenager, and, together with his two siblings, Andreatta grew up in Langley, a suburb of Vancouver. Although he’d visited his maternal grandparents on the reserve during summers throughout his childhood, he’d spent the bulk of his life disconnected from his land and culture — a gap he’d longed to close for as long as he could remember.

“My whole life, I’d been seeking a stronger connection,” he says. “I always felt kind of deprived of it on the mainland, not in a malicious way, but just far away and curious, knowing that there was something bigger.”

In 2012, his first year in the University of British Columbia’s First Nations and Indigenous studies program, he’d tried to conduct a research project on pentl’ach but got discouraged. “I reached out to family members to try to understand what had become of the language,” he says. “But all I heard was ‘extinct, extinct, extinct. Formerly this; formerly that.’”

Andreatta never accepted that label. “There are all these misconceptions and lies that were meant to fragment and fracture every piece of our identity,” he says. “And a lot of those, like the ‘extinct’ definition, were never true.” Like many other Indigenous people, he rejects the historical linguistic and anthropological terms “extinct” or “dead” to describe his language, preferring “sleeping” or “dormant.”

In his final year of studies, Andreatta had another chance to delve into his people’s language. This time around, he made an astounding discovery. Buried deep in the University of Washington’s archives, he learned, were volumes of research related to pentl’ach by M. Dale Kinkade, an American linguist known for his work on Salishan languages. It was a mountain of linguistic research his community had known nothing about.

Andreatta travelled to Seattle to find out more. Although steeped in possibility, the trip’s bite wasn’t lost on him.

“Having to drive across the border, go into the basement of one of these weird libraries in a big university and find pieces of our identities and language there, and then be told to be careful with them and not to touch the documents too much. That’s why we didn’t know it was there, because it was behind walls of security.”

Ultimately, the trip paid off. Kinkade’s research included several hundred pages of detailed analysis of Boas’s work. Andreatta wasn’t exactly sure how it would be useful, but he knew it was important. He photocopied as much as he could and, in another piece of painful irony, had to pay about $300 to do so. Then he headed home.

***

A few months after his trip, Andreatta told his uncle and cousin about his discovery of Kinkade’s work. Then, for the most part, he set it aside. He went about his life in the city — graduating university and taking a job, all the while considering how he might take the language work forward.

It wasn’t until a year and a half later, in mid-2018, that he received the call from his uncle to attend the meeting that would change his life. “It was kind of out of nowhere,” says Andreatta. “He just called me and told me to meet him and my other uncle at this building.”

That September, Andreatta found himself in a provincial government office in Nanaimo, B.C., seated at a boardroom table with his uncles Chief Recalma and Bill Recalma. Bill Recalma, whose traditional name is Og wil a (“the wise one”), is the chief’s older brother and Jessie Recalma’s father. Rounding out the group was Sarah Quinn, an assistant negotiator with the B.C. Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation.

Unbeknownst to Andreatta, over the previous several months, Chief Recalma had been assembling the pieces to set a language revitalization project in motion. On learning about the Kinkade research, he had contacted Quinn, whom he knew from her work with the provincial government, to see if she could find any financial support for the language work. It turned out, she could.

Two key moments from that meeting stand out to Andreatta. One was the signing of an agreement, with which the province committed seed funding for a pentl’ach language revitalization project. The other was his dawning realization of the role he would play. “The project needed a doer,” he says. “I was to be that doer.”

The enormity of the task was immediately apparent to Andreatta. He initially kept his day job and apartment in Vancouver while trying to move the language project forward from afar, with frequent trips to the community. “Those early stages were pretty stressful. I had to wear many different hats. I had to be the administrator, the project manager, the bookkeeper, the linguist,” he says. “I just kept my foot on the gas.”

From the start, he understood that bringing back the language held enormous healing potential for the community. At the same time, he knew it would open old wounds. “We’re dealing pretty directly with our own traumas and then talking with people about the language and why it’s not there,” he says. “I looked at my role as a painful one; it feels like I’m here to pick at a scab.”

***

In the first few years, Andreatta focused on engaging community members, and the initiative began to gain traction. By spring 2019, the Nation’s band council had officially approved the plan, and in late 2020, the project received key funding from the First Peoples’ Cultural Council, a provincial Crown corporation that supports language and cultural revitalization for First Nations in British Columbia.

That injection of funds allowed the team to hire a project manager and bookkeeper, and to officially bring on board three knowledge keepers who would prove integral to the work: linguist Suzanne Urbanczyk and father-and-son team Bill and Jessie Recalma. Bill Recalma is what’s known as a silent speaker — someone who heard the language as a child but had never spoken it. Together with a cousin, he spent much of his childhood with his great-uncle Alfred Recalma, a semi-fluent speaker, which is when he learned the words and phrases that, until recently, he’d held locked inside.

“Our uncle had a cabin in Qualicum Bay. We lived with him in the cabin, and he’d take us out back and teach us the names of the trees and the bushes, the pentl’ach names,” says Bill Recalma. “Then in summer, he’d take us out on his trawler. It was the old style of fishing where he had the big poles, and when a fish hit the hook a little bell would ring. He’d tell us what the name of the coho or a spring salmon was. It was all in the language, and he’d teach us while we were doing it.”

But his great-uncle’s teachings came with a strong warning: “He’d say, ‘Don’t ever speak it, because you’ll get hurt or be in trouble.’”

Bill Recalma didn’t attend residential school, as his great-uncle and parents had, but he endured bullying as a child. “I had lots of relatives at Kuper Island and Port Alberni [residential schools], so I’d go to visit them, but they beat me up because I went to a public school. Then I’d go to public school and get beat up because I was Native. You didn’t need to add the language as another layer of reason for people to give you a hard time.”

The trauma was enough for him to heed his great-uncle’s warning for more than six decades. But when his son, Jessie Recalma, approached him to be part of the pentl’ach language revitalization work, he decided it was safe to open up, if cautiously. “[Jessie’s] the only one I trust with it,” says Bill Recalma. “He’s got a way of talking with me. I can start remembering the words, because there’s no pressure. That means a lot to me because when I was younger, there was pressure. And hurt.”

Although he has no formal linguistic training, Jessie Recalma speaks and teaches Hul’q’umi’num’ (pronounced HALK-ah-ME-num) and understands words in a few other Salishan languages, the linguistic family of both pentl’ach and Hul’q’umi’num’. (There are 23 in total.) This allows him to transcribe the words his father remembers, adding them to Boas’s vocabulary list. “I search as best I can for the different cognates from the most relevant languages — island and mainland K’omoks, Sechelt, Squamish and Hul’q’umi’num’ are the primary ones I go to,” he says.

He also works closely with Suzanne Urbanczyk. An associate professor of linguistics at the University of Victoria, Urbanczyk is an expert on Salishan languages and how languages change over time. “I know about sound systems, writing systems,” she says. While she has supported other Indigenous communities on Vancouver Island in their efforts to revitalize language, pentl’ach is the first sleeping language she has worked on.

To guide her, she takes cues from other once-sleeping languages whose revitalization efforts are further along. Myaamia, the once dormant language of the Miami tribe in Oklahoma, now has about 100 speakers or semi-speakers. Wendat is being revived in Quebec using documentation by Jesuit missionaries. And Wôpanâak, the language of the Wampanoag people in Massachusetts, is now being taught to learners from preschool to adult. (In the 1990s, Mashpee Wampanoag citizen jessie “little doe” baird had a series of dreams similar to the one Chief Recalma had, prompting her to launch the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project.)

“But those languages have far more documentation than pentl’ach,” Urbanczyk says. With a mere 1,000 vocabulary words and six traditional stories contained in Boas’s journals, and no audio or video files, records of pentl’ach are scarce.

Thankfully, the Kinkade research that Andreatta uncovered has proven useful. “He worked with the documents from the Boas corpus, and he made a database. It’s wild how much work he did,” says Urbanczyk. She explains that Kinkade also converted Boas’s notes into the Americanist Phonetic Alphabet, a writing system used by linguists, saving a painstaking step in the reconstruction process. “I found that, personally, very helpful.”

While some of the Boas material remains a mystery, Jessie Recalma tracked down the German linguist Rainer Hatoum, one of the only people in the world trained to decipher Boas’s cryptic shorthand. In addition to supporting the project from a distance, Hatoum planned to travel to Qualicum Bay this summer to help decode more of the Boas notes. Meanwhile, Urbanczyk recently received federal funding to create what she calls a grammatical sketch. “It’s like an outline of the key patterns in the language,” she says. “What are the basic sentence patterns? And how do you make new words?”

***

The revitalization effort still faces a long uphill journey to get to where pentl’ach is thriving once again. One hurdle is securing ongoing funding. Although both provincial and federal governments and many major churches in Canada help fund language revitalization projects, there’s never enough to go around. This is especially true in British Columbia, a hotspot of Indigenous linguistic diversity, with 204 First Nations speaking 36 distinct languages and at least 96 different dialects. Further, most grants are aimed at supporting the transmission of a language from speakers to learners, and “pentl’ach doesn’t fit that framework very well,” explains Urbanczyk.

Critical reconstruction work needs to happen first.

Another challenge is the tension between community expectations and the time needed for the foundational work of language reconstruction. To maintain enthusiasm, the language team regularly holds Zoom-based workshops, and team members have developed learning materials — including an alphabet chart and vocabulary flash cards. “We even translated ‘The Hokey Pokey’ and ‘Head and Shoulders’ into pentl’ach,” says Urbanczyk. A pronunciation guide is also in the works.

More on Broadview:

- This Vancouver bookstore is more than a business — it’s a platform for justice

- ‘North of North’ tells a story rooted in Inuit joy

- The true origins of the Cree writing system

In late 2023, the project hit a major milestone when the First Peoples’ Cultural Council and the province acknowledged pentl’ach as the 35th living First Nations language in British Columbia. “To hear the whole thing acknowledged by somebody, by a minister, is amazing,” says Chief Recalma. “You can’t imagine how full the heart was at that point in time.”

A couple of years ago, Andreatta moved to Qualicum territory to fully support the pentl’ach project. He says the journey has been hard but intensely meaningful.

“My whole life has been about getting back here and finding out who we are,” he says. “It’s been really beautiful to watch my aunts and uncles, sitting there talking about our language, about who we are. Never in my life had I seen that. I’d always wanted it, but I’d never seen it.”

Ultimately, success will depend on the involvement of a younger generation. And although so far, no youth have shown interest — most of the 15 or so people who attend the workshops are over 50 — hope may lie in those even younger.

Not quite a decade after Chief Recalma’s ancestors came to him in a dream and urged him to wake up their language, his own great-nephew is learning pentl’ach. Jessie Recalma’s three-year-old son, Tayash, whose name is pentl’ach for killer whale, converses in a jumble of Hul’q’umi’num’, Squamish and pentl’ach, the languages spoken by Jessie and his partner. Another son is on the way, and the parents hope that he, too, will embrace the languages of his ancestors.

“It’s pretty special,” says Bill Recalma, of hearing his grandson utter pentl’ach words and phrases. “He’s without the fear. And it’s nice not having the fear anymore.”

***

Julie Gordon is a writer in Victoria.

Vanessa Kennedy, who served as a sensitivity reader for this article, is an Indigenous consultant in Hillsdale, Ont.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September/October 2025 issue with the title “When a Language Wakes Up.”

Mary Point spoke at Canadian Mwmorial United Church on Sunday. She walks with such Grace in her being. Mary invited us into a fresh experience of Indigenous People. Much grariude Rev. Cathy Merchant for inviting Mary.