I never imagined that one day I would feel daunted by a lesson schedule, but there it was, on April 28: Israel and Palestine. After a few years teaching after-school Jewish classes to students who are in the public education system, I have most of my teaching methods and lesson plans set: we make candy Torahs at Simchat Torah, we use theatre to tell the story of Jonah and the whale, we host a chocolate Seder to get ready for Passover.

But when I saw in April that I would have to deliver a lesson on Israel and Palestine, I drew a blank. Not least because the lesson was for nine- to 11-year-olds.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

I couldn’t figure out where to start. Trying to find a video that could encourage conversation proved fruitless — everything I found online was either extremely pro-Israel and anti-Palestine, or extremely pro-Palestine and anti-Israel. I wanted to teach the conflict as a part of our history as Jews in the diaspora, but first I wanted my students to develop an objective understanding of the history.

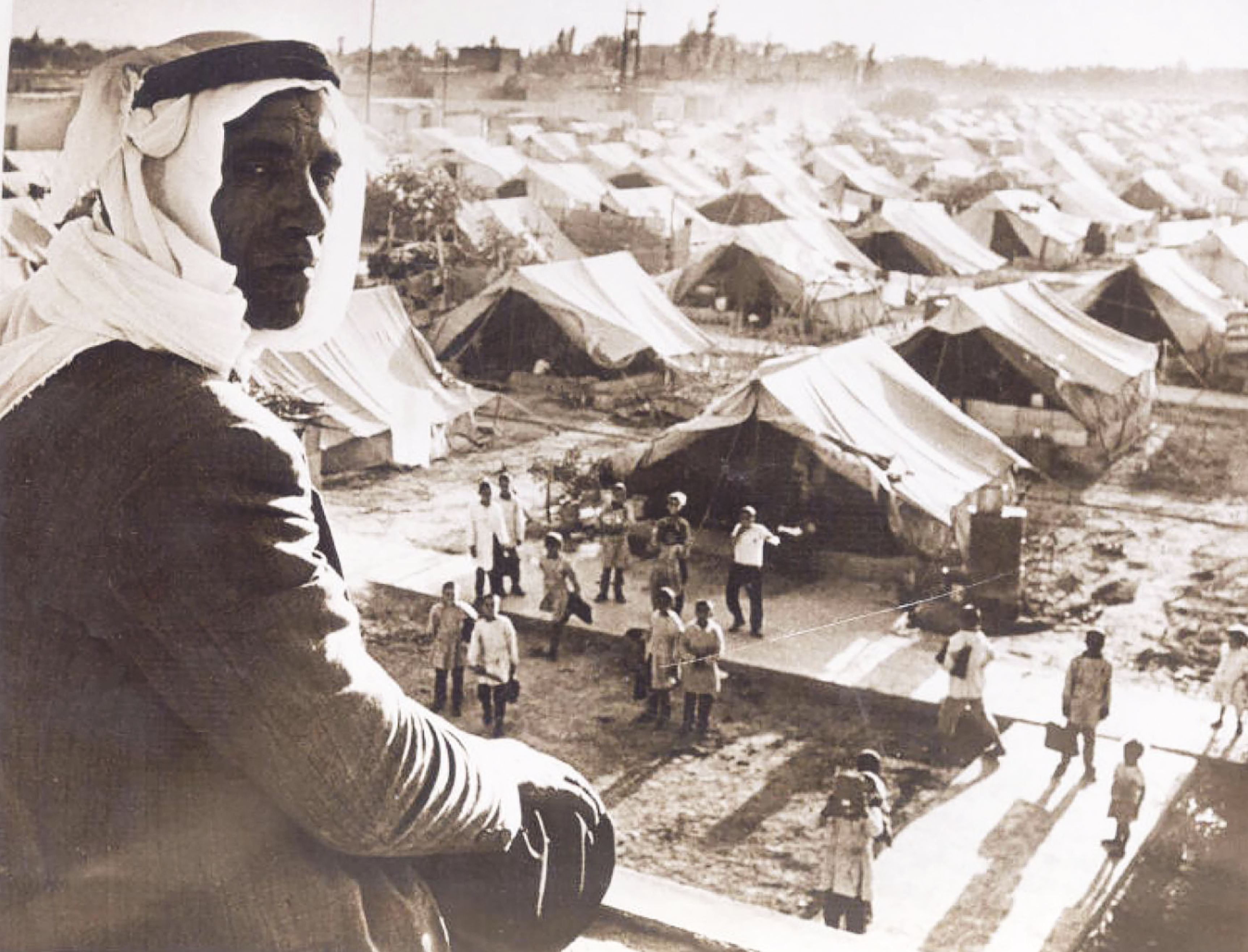

I soon realized there is no neutral place from which to approach the issue. Growing up, my Jewish education was explicitly Zionist. There was room for some critical questions, but we never spoke much about the experience of Palestinians — past or present. We certainly didn’t learn about the Nakba (“disaster” in Arabic), the 1948 forced exodus of over 700,000 Palestinians from their homeland. For me, teaching about Israel and Palestine meant first recognizing what had been missing from my own education.

More on Broadview: Palestinian activist informs the world through social media

To find materials for my lesson, I turned to Zochrot, an Israel-based NGO that provides resources for just this purpose. My class focused on the story of Ayn Ghazal, a Palestinian town that was attacked and whose citizens were exiled during the 1948 war. I brought in three documents from the Zochrot website: a UN report about the attack and expulsion, a testimonial from a Palestinian witness and accounts of the incident from Jewish soldiers. Different students read different documents, and they came together afterwards to tell the story. It was immediately clear: what should have been a straightforward history became three very different narratives. The work for the class was to recognize where our biases lay, and to question our understanding from there.

In describing the Nakba from multiple perspectives like this, I think we were able to develop a kind of empathy that helped us deepen our understanding of the issue without having to decide who was right and who was wrong. What mattered was listening to stories that we might have ignored before, not searching for objective explanations.

When I visit family in Israel and hear their stories about running to safe rooms during rocket attacks, I’m struck by the fact that they, too, constantly deal with the threat of violence, and I want them to be safe. What I’m learning, and what I’m trying to teach, is that honouring Palestinian history doesn’t have to mean negating Jewish history.

The Jewish classes I taught were less formal and less religious than what you might find in a full-time Jewish school, and that might have made it easier for me to lead my lesson in the way that I did. But I hope that, one day, the approach I took will be embraced by all Jewish educators.

This story first appeared in the November 2019 issue of Broadview with the title “Teaching the Nakba.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Thank you for the article. How to frame and teach the facts, origins, and causes of the political unrest between Israel and the Palestinians over the disputed territories in a balanced way ought to be of great concern to all educators. It requires an unbiased examination of the concerns of Israeli and Palestinian. In in speaking specifically about the Nakba (Disaster), I hope you also taught your students the failure of the Arab leadership of the day to accept a partition for peace in 1948. Secondly a close review of the open source reporting on the education curriculum of Palestinian children in the disputed territories ought to leave a diligent Canadian educator wishing to educate and not indoctrinate our children with some concerns. There is enough reporting about anti-Israel and anti-Semitic curriculum being taught to Palestinian children that Canadian educators cant ignore.