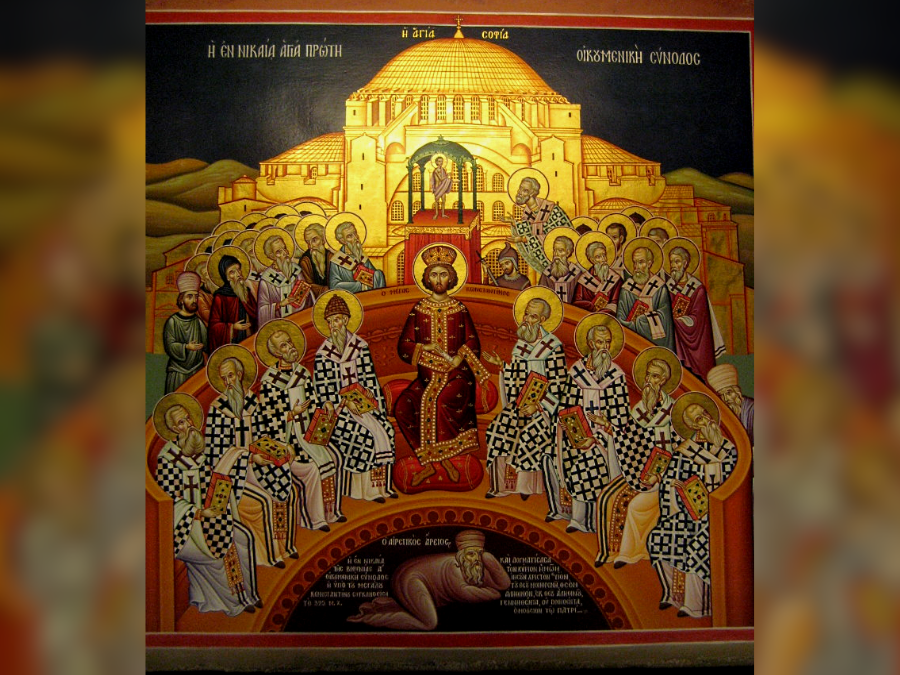

The First Council of Nicaea was a months-long council of Christian bishops in the city of Nicaea, in what is now Turkey, in 325 C.E. The seminal council, which Roman emperor Constantine I convened, brought together leaders from across Christendom to find agreement on basic doctrinal matters. The council upheld the divinity of Jesus Christ and adopted the original Nicene Creed, a profession of faith that is still used in churches around the world.

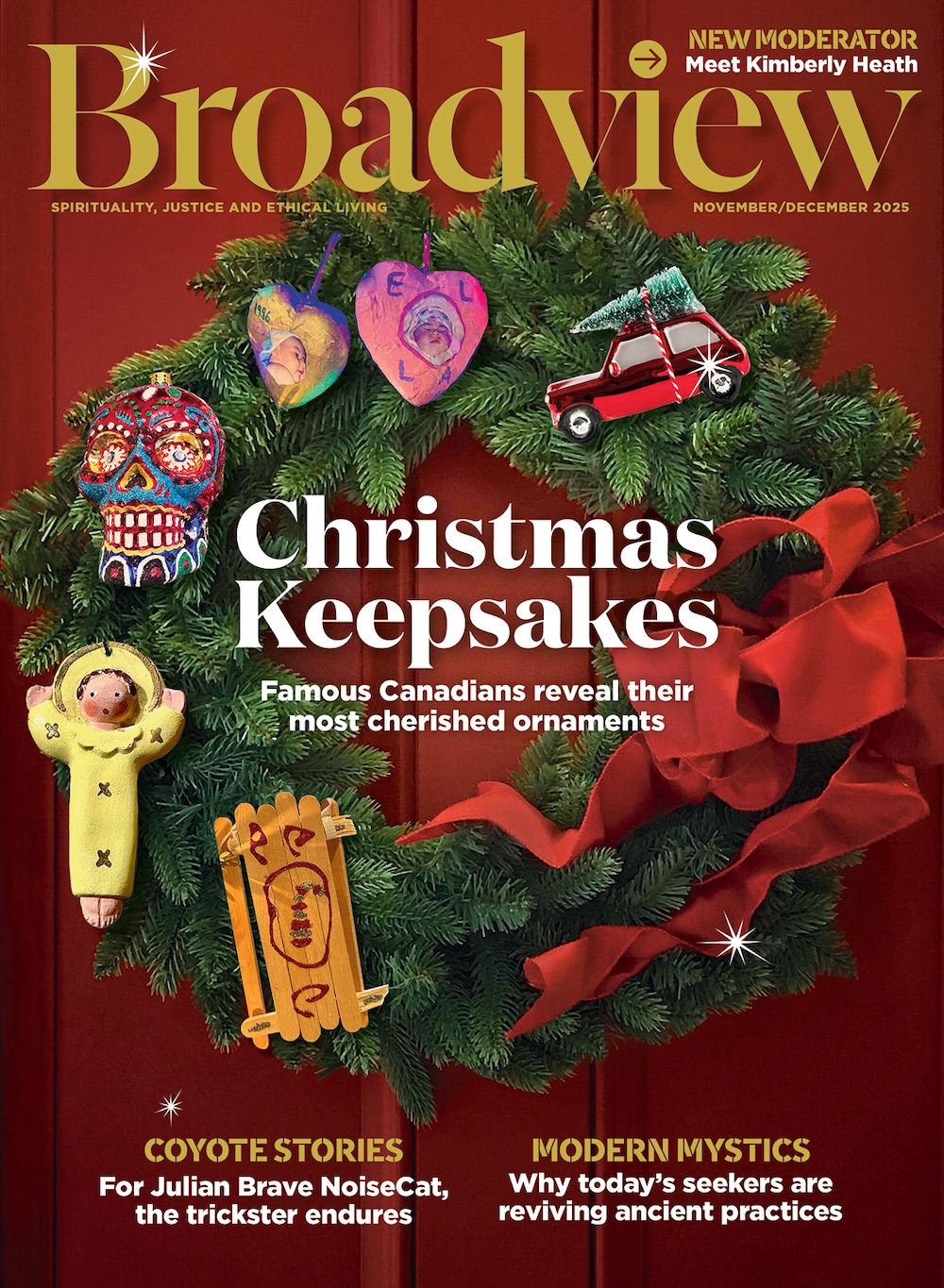

Events are happening around the world in 2025 to mark the 1700th anniversary of the First Council of Niacea, including the Sixth World Conference on Faith & Order in Egypt in October.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

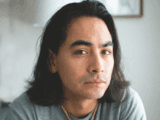

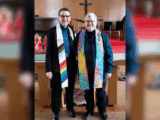

Sandra Beardsall is the United Church’s representative on the World Council of Churches’ Commission on Faith and Order, which is overseeing the WCC’s commemorations of the council of Niacea, including the conference.

Beardsall spoke with Broadview’s features editor Alanna Mitchell over email.

Alanna Mitchell: What relevance does a council from 1700 years ago have for us today?

Sandra Beardsall: Christians are enthused about commemorating this ancient council for many reasons. For me, Nicaea represents a creed, yes, but also a council – a decision-making body — and a context. And that context is startling: a humble religious sect, heavily populated by and often led by enslaved persons and women, only a decade after the end of a brutal imperial persecution. Suddenly it finds its leaders gathered from the ends of a vast empire to sit together and find common cause on matters of faith and practice. These bishops in council managed both to imagine a unified Christianity and to struggle to a fragile consensus.

That moment, not without flaws and controversies, nonetheless unites Christians worldwide, despite all the ways we have since divided ourselves from one another. How did they do it? Through committed leadership, group perseverance, personal flexibility, the willingness to work toward consensus, and most of all, an overwhelming desire that the Christian Church, in all its diversity, would be a shining example of the oneness of the Body of Christ. So, I ask myself and other Christians: can the churches rise to that task today? I hope we can.

AM: How does The United Church of Canada fit into the global Christian mix today? Has that changed in the 100 years since the denomination began?

SB: The United Church of Canada was at the forefront of the “modern ecumenical movement,” which took shape in the early 1900s. As an early “united and uniting” church, it held pride of place in ecumenical forums, including the First World Conference on Faith and Order in 1927. Ecumenical dialogue and efforts were largely European and North American, and the participating churches were mostly Protestant, with a small Orthodox representation. The representatives were mostly white male clergy.

Since then, almost everything has changed, in the United Church and in the Christian world. The “historic” Protestant churches are no longer dominant in global Christianity. Most of them are experiencing the effects of late capitalism and overwhelming secularization.

Now Faith & Order commissioners come from all continents and traditions, and now represent Roman Catholic, Pentecostal, Mennonite and evangelical traditions. There is an active movement in the commission to “broaden the table” – to enter into dialogue with churches who are not World Council of Churches members in the hope of widening the table of belonging. In all this, the United Church of Canada continues to play a role. We are still seen as allies in the search for unity.

More on Broadview:

AM: To me, it seems that interpretations of Christianity are quite fractured and that a particularly literalistic, right-wing version is trying to take hold in certain parts of the world. How do you interpret today’s Christian trends in a historical context? What does the Nicene Creed have to offer in such times?

SB: It is true that in many places, a fundamentalist Christian worldview is more prevalent than two or three decades ago. Our view is especially affected by the Christian nationalism we see dominating political and economic processes in the United States. Yet, there are other trends. The migration of people all over the world means that we are more likely than ever to encounter Christians (as well as other religions) from other continents in our daily lives. Where we live together, there is an opportunity to get to know one another, to dialogue, to befriend.

For example, Egyptian (“Coptic”) Christianity dates back two thousand years. Today, 20 percent of the world’s Copts live abroad, many of them in Canada. Their church and ours both officially accept the Nicene Creed. We have, without knowing or admitting it, a common and ancient link to one another. I think we in the United Church could enrich our lives by sitting with some Copts and learning what that creed means to them.

To study it is to discover more than a very old text; it invites us to experience the depths of our faith, to let it feed our souls and our mission. In troubled times, finding our roots – and our neighbours – can help ground us for the struggle for justice and integrity. We can all use some “light from light” these days, I believe!

***

Alanna Mitchell is a journalist, author and playwright and the features editor at Broadview. She lives in Toronto.

Thank you so much for this affirmation. At Sylvan united on Vancouver Island we just this week hosted a group of Coptic Christians from Egypt, fleeing persecution there. As I prepared and read about our commonalities in faith I was really impressed. The Nicene creed speaks to my heart, it speaks to those in the Orthodox Churches and it unites us as Christians around the world. It is precious! I’m not clergy, just a lay person in my congregation.

I am surprised that we are commemorating this old creed. I don’t think it represents the church today. My understanding is that the United Church is not a creedal church. Can you help me understand this?

The Nicene Creed, lays the foundation of Christianity, so I would hope it still represents the church today.

A Song of Faith is basically a creed for the United Church of Canada. It is a basic set of beliefs for faith.

The Nicene Creed is an ancient document that emerged from a plethora of theological ideas to depict an image of God and Jesus according to the dominant understanding of the time. Not everyone was in agreement with it. It says nothing of Jesus’ teachings which, I find, are most important in that they provide a set of values by which we can live in community with one another. I was taught in seminary to engage in a process of lifelong learning and I’ve done just that. The creed is an interesting founding document but modern thought and science; the knowledge we have now of the immensity of the universe and the knowing that earth and its inhabitants are but a speck within it, as well as the discoveries and future discoveries in quantum physics simply make it a quaint curiosity of days long past.

I belive in God the Father, maker of heaven and Earth, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, our Lord who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried. On the third day He rose from the dead and sits at the right hand of the Father from whence He shall judge the quick and the dead. I believe in the holy catholic church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and live everlasting. Is that the Nicene Creed?

No, that is the Apostle’s Creed – despite the name a later and much shorter one.