On a sparkling morning late last winter, Toronto artist and amateur astronomer Julian Samuel pointed a telescope toward the eastern sky and invited me to take a look at the rising sun.

The naked eye abhors the sun, but a telescope fitted with filters can tame its blistering offences. The instant I leaned into the eyepiece, I realized I was looking at a lifelong companion that I hardly knew. Nothing prepares you for the marvel of seeing the sun close up and first-hand — or as first-hand as light can be when it has taken more than eight minutes to reach you.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

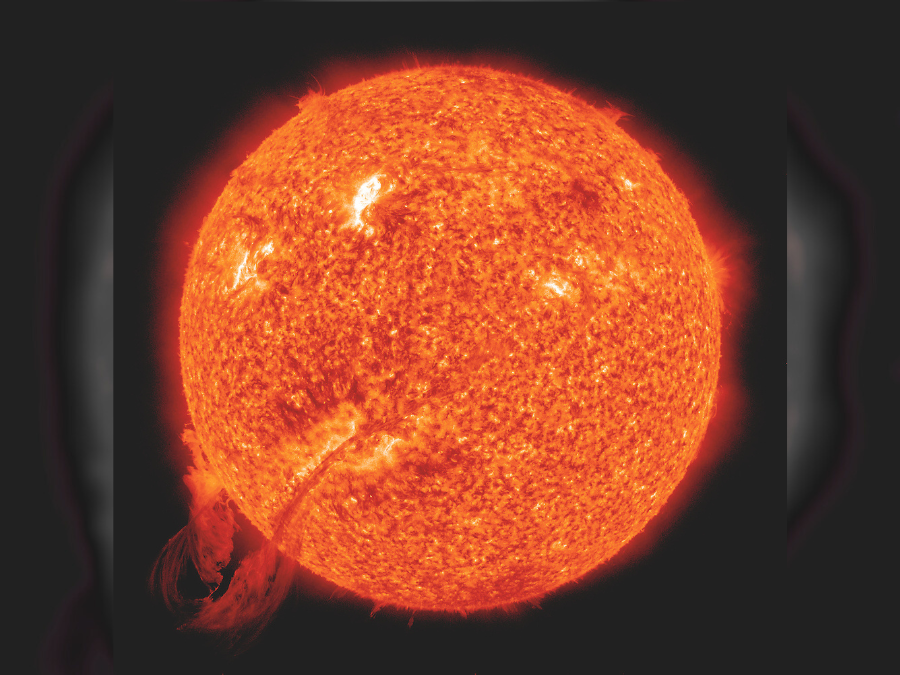

Sunspots, a sign of vigorous magnetic activity, stood out like malignant blemishes against the incandescence of the sun’s gaseous surface. Then Samuel switched to a telescope that brought the sun’s second-outermost layer, the chromosphere, into view by blocking everything except the red emitted by hot hydrogen. Tendrils of plasma called prominences snaked outward, maybe as high as 250,000 kilometres. If I adjusted the focus just so, I could make out the granular texture of the layer below, a roiling battleground of heat and magnetic fury. Our mother star is a sphere of exquisite perfection, immense beyond imagining. One look and you can’t help but wonder how it all came to be.

Samuel knows the feeling. He’s been captivated by the mysteries of worlds beyond our own since he was a child sleeping out on the roof of his grandmother’s house in Lahore, Pakistan. Three years ago, he saw the sun through a telescope for the first time during a visit to the E.C. Carr Astronomical Observatory near Thornbury, Ont. “Immediately the sun became alarmingly unfamiliar,” he recalls.

He could not pull himself away from the eyepiece and was rewarded with one of the most spectacular sights in solar astronomy. “Slowly, a prominence began detaching from the sun. This one looked like a conductor of an orchestra gleefully tossing the baton up into the black heavens.”

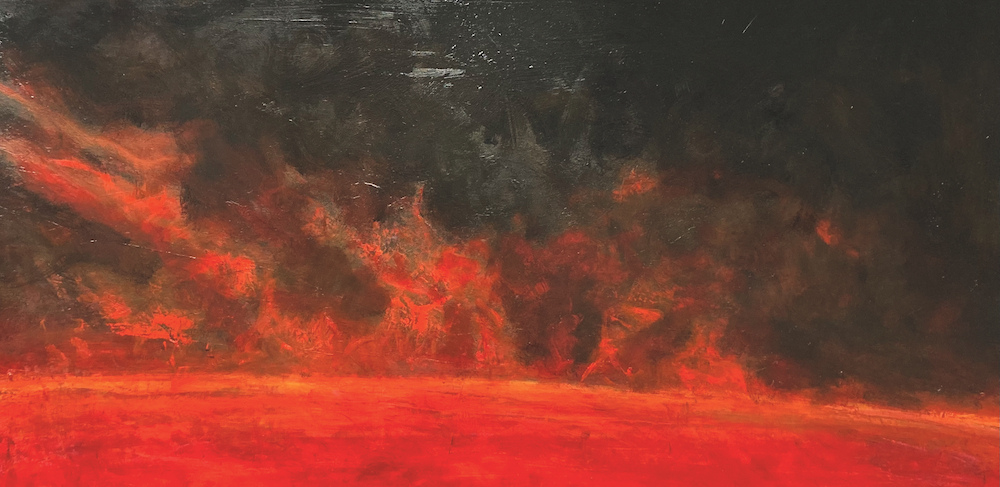

The sun has dominated his paintings ever since. Finished, partially finished and never-to-be finished canvases clutter Samuel’s paint-spattered studio. In the same way, as he observes, that “the sun is always changing its intensity of red, as prominences magically arise and vanish, as sunspots form and dissipate out of view,” no two paintings are the same.

He likens them to “visual observation logs” that mirror the results of his sun gazing and what he’s learned about solar science over several years of formal and informal study.

The passion for science that flows through Samuel’s artwork reflects the energy currently fuelling solar research. Heliophysics, the scientific study of the sun and its influence, is having a moment. It’s a highly specialized and complex business: the sun guards her secrets jealously. But thanks to rapidly advancing technology and an intense new focus, scientists are peeling back layers of mystery that have beguiled humans for as long as we’ve felt the sun’s warmth and shrunk from its extremes.

Satellites in solar orbit, Earth orbit or somewhere in between are delivering vast troves of data and images. Late last year, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe became the most celebrated of these when it ventured further into the sun’s scorching atmosphere than any other spacecraft and lived to tell the tale. In 2020, NASA and the European Space Agency launched the Solar Orbiter, the most sophisticated science laboratory ever sent to the sun, on a mission to investigate solar storms and the solar cycle. Giant ground-based telescopes such as the Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii study the sun’s fluctuating magnetic field and its impact on space weather. Computer modelling reveals clues about the sun’s behaviour that would not be possible to observe first-hand. The more these tools shed light on our mother star, the more astronomers are able to understand the billions of other stars in our galaxy — and the nature of the universe itself.

Heliophysicists now know when and how the sun was born (about 4.6 billion years ago as the result of a giant cloud of space dust and gas collapsing under its own gravity) and when it will die (in another five billion years or so). They know how big it is (it would take 1.3 million Earths to fill its volume), what creates the light and energy it emits (hydrogen fusing into helium) and how hot it gets (15 million C at its core). And they know what creates the sun’s swirling magnetic fields (charged particles set in motion by tremendous heat), as well as when to expect them to interact with Earth.

The way a society perceives the sun tends to inform how artists of the day depict it. With titles like Chromosphere #4, Coronal Mass Ejection #6 and Prominence #3, Samuel’s paintings evoke the ascendency of modern science and technology. Yet, as an artist and would-be solar scientist, he sees himself in league with “early astro-painters who hunted and gathered mental images and returned to decorate their cave walls” with their impressions of the sun. Same with artists through the centuries who’ve conceived of the sun in terms of mythology (the Greek god Helios), religion (Ra, the supreme deity for ancient Egyptians) or even as the divinely ordained realm of kings (Louis XIV, the Sun King of France).

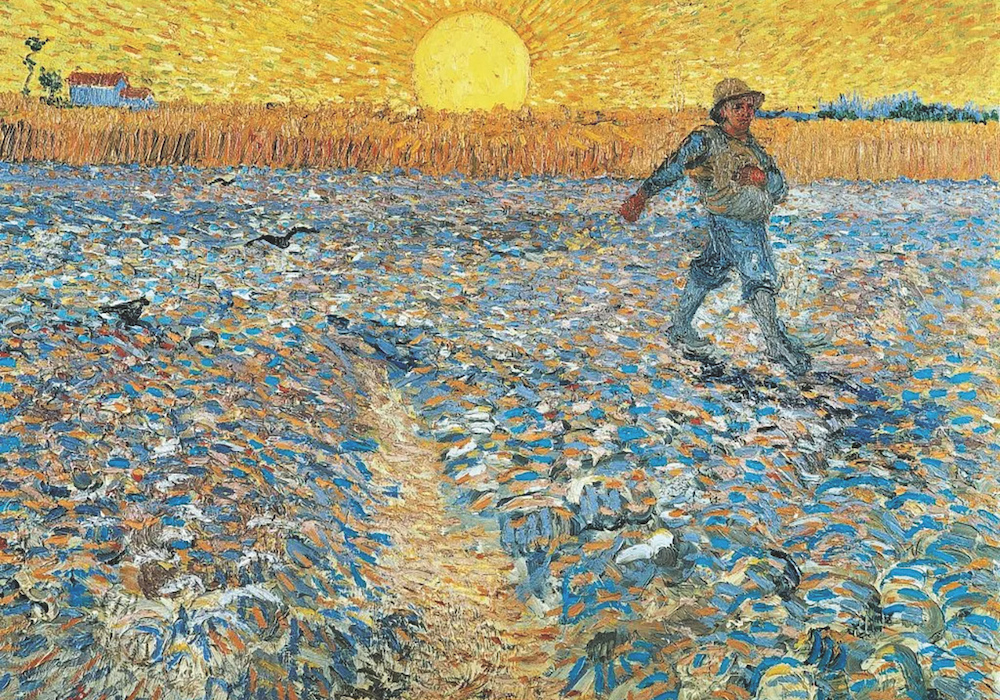

Closer to our own time, Vincent van Gogh’s celebrated efforts to capture the sun on canvas coincided with advances in formal astronomy and the popularization of science in western societies in the late 19th century. As Samuel observes, “He painted in an era which had scientific imagery everywhere: in libraries, in cafés, in bars.” Indeed, the sun looms so large in works like The Sower that van Gogh might well have taken the French astronomer Camille Flammarion at his word when Flammarion described the sun as “Ruler of the World” in the title of a chapter in his 1880 bestseller, Astronomie Populaire.

Capturing the sun demands nimbleness. Artists who paint it implicitly acknowledge the enigmatic forces that jostle and churn to keep it in flux. Brush strokes or tints that seem right one day can miss the mark the next. Van Gogh painted and sketched multiple versions of The Sower, each depicting the sun in different aspects and hues. Some of Samuel’s canvases have been works in progress for about three years; the paintings are as dynamic as their inscrutable subject.

Just as it can confound artists endeavouring to paint it, the sun may ultimately defy the efforts of heliophysicists to unravel the full story of what makes it tick. Despite the increasing sophistication of solar science, mysteries linger. Why, for example, is the sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, thousands of times hotter than its surface? Shouldn’t it be the other way around? Or what causes some solar cycles — periods of fluctuating solar activity lasting roughly 11 years — to peak more dramatically than others? What triggers the solar flares and mass ejections of plasma and magnetic material that produce spectacular aurora light shows on Earth but can also disrupt power grids, radio and internet communication and even impair the operation of automobiles?

Elaina Hyde, who teaches physics and astronomy at York University in Toronto and is director of the university’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory, concedes there are aspects of the sun “that can never be completely modelled because they’re too complex….It’s always going to be a bit of a mystery.”

The installation of an eight-metre sundial near the Carswell Observatory excites Hyde as much as news that researchers in China and France are inching closer to replicating and sustaining the nuclear fusion that occurs in the sun’s core. Well known as an advocate for astronomy outreach, Hyde works with her students to produce weekly podcasts and YouTube videos aimed at the general public. The same spirit imbues the new sundial: it will be a tangible connection to a heavenly body whose embrace holds our solar system together and whose radiance nurtures everything that lives.

My first look at the sun through a telescope last winter couldn’t have been timelier. The sun was approaching the peak of the solar maximum, the point in the solar cycle when sunspots, prominences and coronal mass ejections of plasma and magnetic material are most lively. The burst of activity is linked to another of the sun’s quirks: the 180-degree flip of its magnetic poles every 11 years. It adds up to a bonanza of data for astronomers and inspiration for artists like Samuel. The hours he spent sun gazing during the solar maximum yielded a 5.5-metre-wide triptych that’s a thrilling maelstrom of reds, oranges, yellows and blinding whites set against the blackness of space. The work changes depending on the mood of his subject on any given day.

Which is only fitting. Whether it’s a cluster of the faithful gathered to celebrate the gift of a new dawn, an astronomer processing images of solar turmoil, or an artist struggling to capture an enigma with paints and a brush, humanity’s relationship with our mother star is itself a work in progress. And it’s likely to remain so for as long as she shines down upon us.

***

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September/October 2025 issue with the title “Mother Star.”

David Wilson is a Toronto journalist.