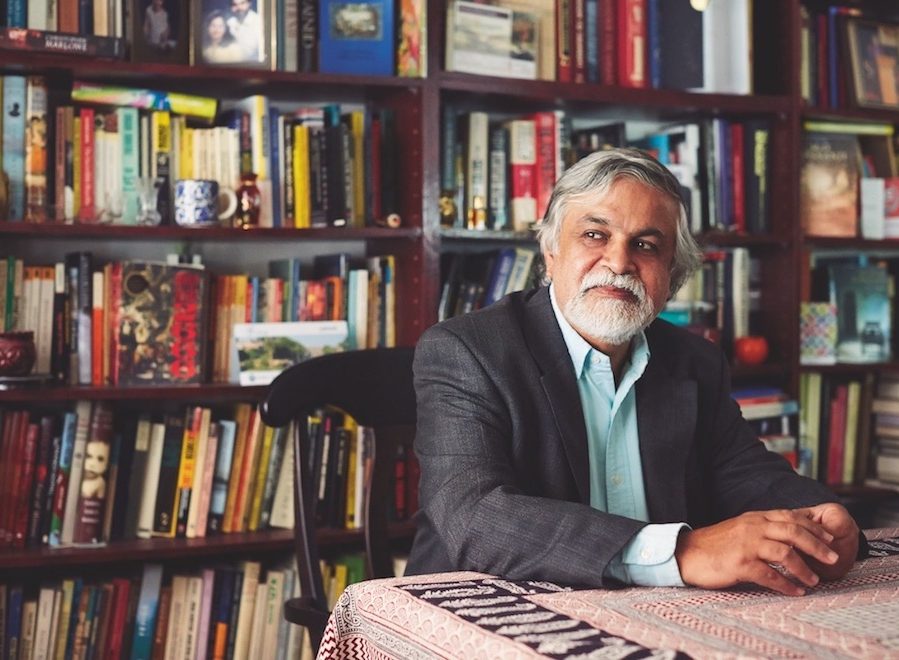

Born in Kenya to Indian immigrants and raised in Tanzania, M.G. Vassanji has lived most of his adult life in Toronto. He weaves rich cultural experiences and memories into many of his works, and his first essay collection, Nowhere, Exactly, is no exception. Released in March, the book of 15 essays dissects ideas of home and belonging through personal recollections and thoughtful anecdotes.

The seasoned writer has a vast bibliography, including novels, short story collections and memoirs. He won the first-ever Giller Prize for his 1994 novel, The Book of Secrets, and earned a second Giller in 2003 for The In-Between World of Vikram Lall. Vassanji spoke to Madeline Liao.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Madeline Liao: You distinguish between identity, which is the box you check on a form, and belonging, which is more visceral and emotional. Can you describe what you mean by belonging?

M.G. Vassanji: Belonging is what you feel when you go to or remember a place, with all its sights, sounds and smells. It’s something that nobody can take away from you. I feel like I belong to Toronto — I know it well. But when I go to my hometown in Tanzania or Kenya, I feel I belong there. Even though the politics may differ, my sense of belonging cannot be taken away.

ML: We’re living in a time when global crises are causing rapid human displacement. How does one reconcile with the concept of home when the place they know is in ruins?

MGV: You still belong there. Many people assume that just because you were expelled or left in a hurry you don’t belong, but belonging is what you feel, not what someone else feels.

It causes great pain to see a place you feel you belong to destroyed, but as you grow older, you realize that destruction is temporary and things always grow back; they change with time. Throughout the world, things have been destroyed and rebuilt.

ML: You mention that the task of a storyteller is to “remember, to imagine and recreate.” What role does your work play in documenting cultural memories?

MGV: I feel the need to remember what I lost — not only in the past but also for the future. Because to have a future, you need a sense of who you are and where you came from.

When I first came to Canada from the United States in 1978, the people from East Africa I met didn’t care about the past. But as decades pass, they start remembering and writing biographies for their children and exchanging stories. When the end of their life arrives, they want to feel that they belong and came from somewhere. I find that sense of identity remarkable.

ML: Is it ever too late to start looking back?

MGV: I don’t think so. It doesn’t cost you anything, and it gives you a sense of peace.

More on Broadview:

-

A tale of two lives: Danny Ramadan on writing while queer and brown

- ‘Dayspring’ reimagines the Christ story through a queer, pop-culture lens

ML: You observe in the book that displacement often strengthens faith. In what ways does religion support or hinder belonging?

MGV: It hinders belonging in the sense of excluding everything else. For example, people may want only to marry or do business within their religious community. But faith also has a great psychological benefit. When people are out in the world, they remember the God they grew up with and it’s comforting. To me, true spirituality moves across borders — it’s inside you.

ML: In the essay “Nowhere with God,” you describe how your religious upbringing in the Khoja community in Tanzania combined Hindu mysticism with Islam. But this traditional syncretism is now being replaced as leaders embrace a purer form of Islam. What do you think is lost in this shift?

MGV: If an identity becomes pure, it also comes with certain demands. A kind of freedom is lost. You’re more closed off, putting more restrictions on yourself. You lose the ability to accept different forms of belief, spirituality, mythology and stories. Somehow, people designate stories as strictly Muslim or Christian, for example. To me, that is nonsense.

ML: You mention in the book that labels make you squirm, as they are often imposed on a person rather than chosen. How does the way we categorize literature affect how it connects with readers?

MGV: People don’t want to read across cultures. They put you in a category and say that category doesn’t interest them without seeing the humanity behind the work.

If I read a novel by someone from a different culture, I can still find connections with those writers despite their differences. I think labels take away from that.

But I’ve noticed in a cosmopolitan place such as Toronto, people who read literature are more open to other experiences — and those are the kinds of people who read my books.

ML: In your seventh essay, “Am I a Canadian Writer?,” you ponder what it means to truly be a “Canadian” writer. How has the Canadian literature scene changed throughout the years?

MGV: More writers of colour are now being published and read, which has changed dramatically from the past. I don’t know what it means in the long run. Whether or not the change is real and long-lasting remains unclear, but at least on the surface, things have changed quite a bit.

ML: This is your first essay collection in a career of mainly writing novels and memoirs. How did the experience of writing these shorter personal essays differ from your usual writing process?

MGV: These essays came about coincidentally while preparing lectures about my writing or personal experiences. I had given talks over the years in various places. At some point, I decided to put them together. I wanted to leave a record of my thoughts and what I’ve experienced.

ML: This collection is a culmination of your life. What is a lesson you have carried with you through the years?

MGV: The teaching I was brought up with is that life is finite, so at the end of the day, nothing really matters. But you do your best because that’s what keeps you alive. Writing keeps me alive, and as long as I can do it, I will do it. Just as I breathe air, writing is like my breath.

***

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Madeline Liao is a recent Broadview intern.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2024 issue with the title “Coming from Somewhere.”