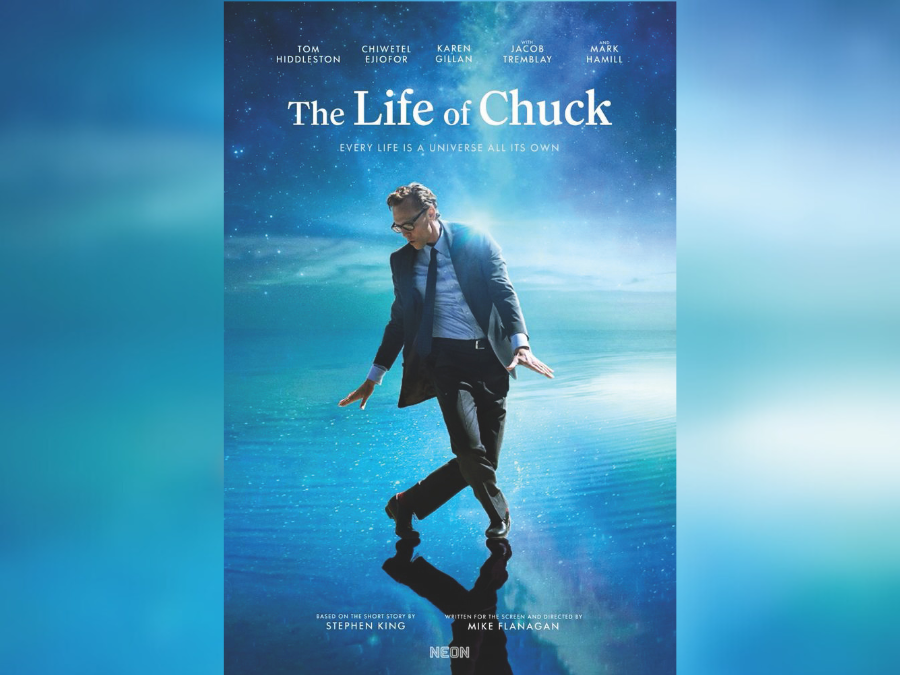

When the televisions cease to work in The Life of Chuck, it’s almost a relief, given their 24-hour coverage of the world’s catastrophes. So too with cellphones, the internet and just about everything else. In the early scenes of Mike Flanagan’s new film, the increasing fallibility of the tech we rely on is just one sign of total societal collapse. Things are marginally less grim for Felicia (Karen Gillan), a doctor, and Marty (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a schoolteacher and Felicia’s ex, in their small city than it is for the people of California, much of which has fallen into the Pacific due to earthquakes. Yet they’re still facing dispiriting hardships, and the strength to carry on gets harder to find.

That’s why Marty becomes fixated on a sign he starts seeing all over the city featuring a smiling office worker named Chuck (Tom Hiddleston). “Thanks, Chuck!” the sign proclaims, for “39 great years!” This symbol of goodwill and gratitude stands in stark contrast with the hopeless circumstances. It also becomes the centre of a mystery as the story moves back in time to depict significant moments in Chuck’s life, revealing the connections between this Everyman and the looming apocalypse. In so doing, The Life of Chuck evolves into a poignant celebration of love and kindness in the face of loss and darkness.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The movie is full of unexpected pleasures — and even a dance sequence or two. Just as surprising is the fact that something so life-affirming could be the handiwork of two people better known as masters of terror: Stephen King, whose 2020 novella is the film’s basis; and screenwriter and director Mike Flanagan, who shares King’s reputation for delivering scares thanks to his many movies and Netflix series, such as The Haunting of Hill House.

The two previously teamed up on projects like Flanagan’s 2019 adaptation of King’s Doctor Sleep. But what they’ve done here strikes a different chord. For decades, the Toronto International Film Festival’s People’s Choice Award has served as a bellwether for award-season success, with Oscar winners such as Slumdog Millionaire, The King’s Speech and Green Book all claiming the prize on the road to future triumphs. So when Flanagan and King’s relatively little-known effort outflanked favourites like Anora to win the award last September, it scored a major underdog victory. Now, amid a year full of global developments nearly as trying as those faced by Felicia and Marty, it feels like those TIFF-goers knew how badly other viewers might need the respite it offers.

As the summer movie season’s most unlikely crowd-pleaser, The Life of Chuck also challenges our usual expectations about a time traditionally dominated by superhero-stuffed spectaculars, animated family films and sequels galore. One prevailing assumption is that Hollywood’s primary product has always been escapism. It offers viewers a chance to leave their troubles behind and find comfort in fantasies. This explains the popularity of lavish musicals during the Great Depression, or the romantic melodramas and manly westerns that offered other forms of reassurance.

Any work that overtly aims to please viewers risks inviting the umbrage of those who believe art must have a higher purpose. Work that merely entertains is a poor substitute for that which opens our eyes to discomfiting truths, they would argue. Art should enrich and ennoble — the rest is not worth trusting.

More on Broadview:

- ‘North of North’ tells a story rooted in Inuit joy

- ‘Hazbin Hotel’ is a darkly humourous dive into redemption and sin

- ‘We Are Lady Parts’ mixes humour, music and big questions around Muslim identity

This bias has long been embedded in the discourse of big thinkers who’ve spent millennia debating about art. It remains a somewhat radical idea that a work may still have value if it lands somewhere between sentimentality and seriousness. A philosopher who was hardly known for his positivity, Friedrich Nietzsche, nevertheless saw great value in art’s ability to provide solace. In his 1872 book, The Birth of Tragedy, he describes art as nothing less than “a saving sorceress, expert at healing,” praising its ability to turn “these nauseous thoughts about the horror or absurdity of existence into notions with which one can live.”

In their 2013 book, Art as Therapy, writer and philosopher Alain de Botton and author John Armstrong push for a similar interpretation of art’s purposes, countering the notion that work which values beauty or kindness can only signal a retreat from reality. Instead, they suggest, it represents a deeper engagement. “We are only too aware of the problems and injustices of the world — it’s just that we feel debilitatingly small and weak in the face of them,” they write. “Cheerfulness is an achievement, and hope is something to celebrate.”

That last idea feels central to the appeal of The Life of Chuck, which Flanagan says he was moved to make after reading King’s novella during the early stretch of the COVID pandemic. Nevertheless, it’s also easy to discern notes of resistance to the movie’s optimistic spirit in many of the early reviews. In rewarding the film, TIFF audiences expressed far more enthusiasm than the Variety reviewer who decried its “saccharine” tendencies.

It’s worth noting an earlier generation of critics had similarly harsh things to write about It’s a Wonderful Life, long before Frank Capra’s film was entrenched as a holiday classic. The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael famously assailed it as “doggerel trying to pass as art.”

There’s never a lack of scorn for those seemingly frivolous distractions whose primary purpose is to make the world a little easier to bear. Director Preston Sturges slyly illustrated that fallacy’s inherent dangers in Sullivan’s Travels, one of the funniest Hollywood movies of the 1940s. The title character is a Hollywood director whose run of light–hearted hits has prompted a crisis of faith and a desire to make a more important statement.

Seeking a more authentic reflection of “modern conditions,” he tells his worried producers his next movie will be “a true canvas of the suffering of humanity.” He then abandons his pampered lifestyle to research the daily realities of the less fortunate, only to experience one ugly comeuppance after another.

He reaches his lowest point after being sentenced to work in a prison chain gang. As a treat one night, he and his fellow prisoners are herded into a church to watch a comedy. Laughing with the rest, the director finally realizes what his earlier work was worth.

The Life of Chuck’s best moments brim with the same feeling: joy stubbornly persisting in hostile circumstances. Of course, viewers are more than free to find it too sappy, too corny and too odd (especially if they don’t care for dance numbers). But others may feel grateful for the warm glow cast by Flanagan and King’s fable about treasuring what’s good and preserving it however we can.

***

Jason Anderson is a writer and film programmer in Toronto.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “In Praise of Kindness.”