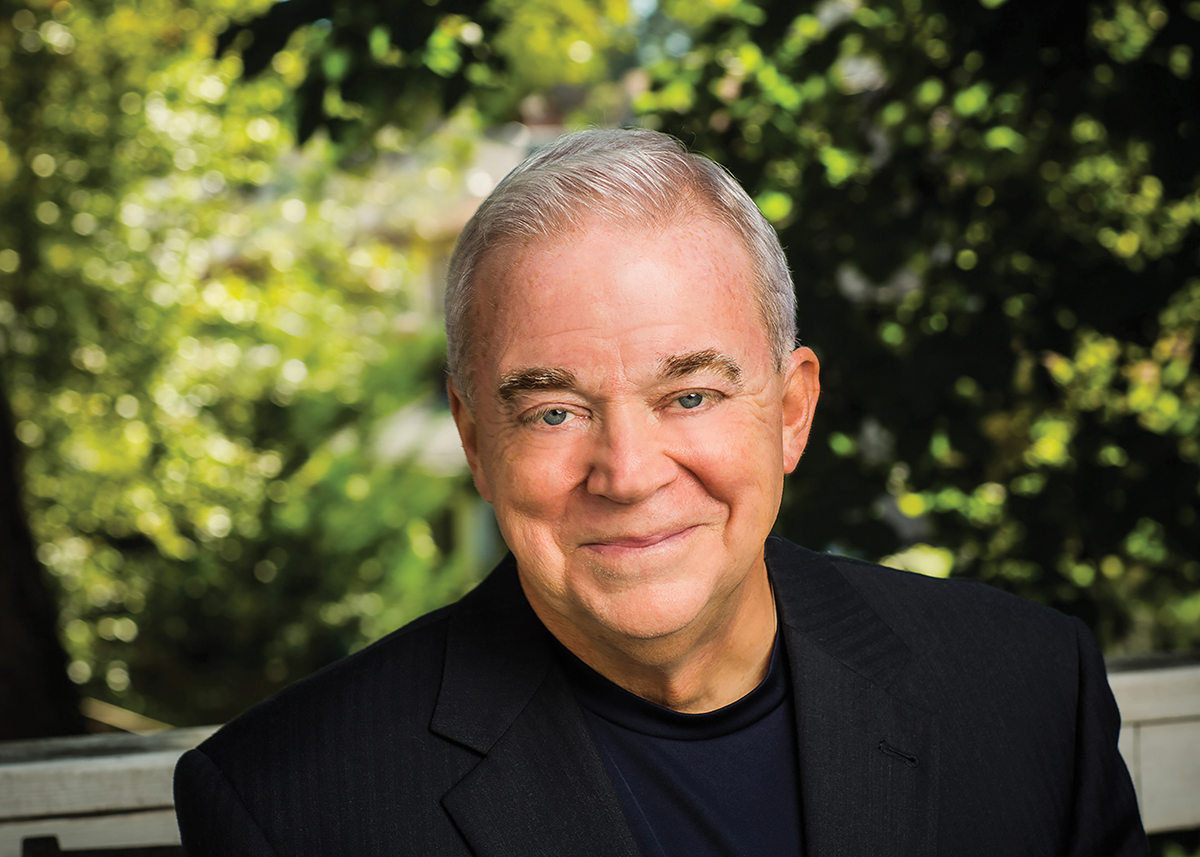

Q You and I were at the wake last May in New York City for Rev. Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit priest and anti-war activist. That night, you spoke about how Berrigan kept your own faith from dying because he was an activist Christian living what you thought the gospel called for, when nobody in your white evangelical world in Detroit saw it that way.

A Well, when I got kicked out of my [Plymouth Brethren] church as a teenager over issues of race and civil rights, a few people kept my hope alive. Berrigan was one of those people who showed me that you could be a Christian and against the war in Vietnam. He kept my faith alive.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Q You continue in that tradition of keeping hope alive, particularly for those committed to social justice. Before last year’s presidential election in the United States, you and many other American faith leaders issued a statement, “Called to Resist Bigotry,” that described Donald Trump’s message and tactics as contrary to Christian values. Now he is president. So what do we do?

A In terms of traditional Christian values, he is the antithesis of those values. And he actually ran on racial bigotry. What is often implicit in American politics, he made explicit. The election revealed an incredible racial divide in this nation.

Canadians need to realize what happened here. A majority of white people on every level — not just white working class, but every level and without a significant gender gap — voted for Donald Trump. And people of colour overwhelmingly voted against him.

You hope there’d be some leaven or salt or light from Christians. But white Christians voted exactly like their white tribe.

The majority of white Christians — white Catholics, white mainline Protestants, white evangelicals — all voted for Trump. Christians of colour voted against Donald Trump. And Christians of colour are saying to their white brothers and sisters, “Clearly, racial bigotry wasn’t a deal breaker for you. . . . You voted against me. You voted against my kids. You voted against us being part of this country.” So we have more distrust than I’ve seen in my lifetime between Christians of colour and white Christians.

We recently had a faith leaders’ retreat with heads of churches and faith organizations. We were able to share reflections and emotions. Many are terribly afraid because they were targeted by Donald Trump, and they have already been attacked in a tremendous escalation of verbal and physical assaults.

So this is what we do. We turn to Matthew 25, the words of Jesus, who reminds us that how we treatthem is how we treat him. This text is rising up all over the country. Individuals, congregations, organizations and denominations are being invited to sign the Matthew 25 Pledge: to protect and defend vulnerable people in the name of Jesus.

We will focus on three groups of people: young people of colour who are in danger of racialized policing; undocumented immigrants who are in danger of being deported; and Muslims who are in danger of being registered and who knows what else. You’re going to see Christians forming circles of protection around those particular groups of people who are in most danger.

Q You speak of seeing more distrust than ever before. What have you learned over the years about what builds trust and how social change really happens?

A It happens when we deepen our faith and deepen our relationships. If our faith deepens and our relationships get stronger, who knows what kind of spiritual and even political influence might come from this time, ironically?

The frame that I’m using is faith, resistance and healing. This isn’t going to be a time of reform, of changing things for the better. It’s a time of resistance. And in those times, your faith can go deeper. I think there’s going to be a deeper movement of faith and justice in this country.

When we actually read what our scriptures say, and do what is said, churches will have to say to the president, “You can’t deport hard-working, law-abiding, contributing immigrants.” Jesus calls them the stranger, and we’re going to welcome them into our churches, our seminaries and our homes. We’re saying to the police, and to Donald Trump, “If you arrest those immigrants, you’re going to have to arrest them in our churches and in our homes.”

When it comes to policing and young African American men who are in grave jeopardy, we’re going to go to every sheriff in the country and say, “We’re the clergy in your community.” We’re going to shake their hands and say we want to work with them on community policing, which is good for all of us, and good for police too. And we’re going to hold them accountable for any racialized policing: “We’re going to film you; we’re going to record you; we’re going to watch you; we’re going to be in the streets with the kids; and you’ll be held accountable by the clergy in this town for obeying the law in regard to all your citizens.”

And if they register Muslims, I can tell you that Christians and rabbis will be the first in line. Muslims will have a hard time getting in line because we’ll be ahead of them.

Q In your call to resist bigotry, you refer to the golden rule — to treat others as we would want to be treated. How do you intend to treat President Trump?

A We’ll treat Donald Trump fairly. We’ll tell him what we’re going to do, and what he should do, from our perspective. We’re asking him to do what the Bible tells leaders and kings to do, which is to protect the vulnerable. Maybe we’ll help with his biblical literacy.

Q Do you see evidence of a moral core in Trump to which you can appeal?

A No, I don’t. I gave you an honest answer. But we appeal to kings and rulers on the basis of our principles. They need to hear from the people of God about their responsibilities.

Q In Canada, faith leaders have less influence on public discourse. What are your thoughts on how to be influential in an increasingly secular context?

A The two great hungers are the hunger for justice and the hunger for spirituality, and these two are deeply connected. One without the other is dangerous.

So this presents us with a moment to act in faith. If we do that in ways that show commitment and even courage, it could be a moment of putting faith into action.

Q At Dan Berrigan’s wake, we heard how Dan would ask family members, “What gives you hope these days?” How would you answer Dan today?

A Hope is the most important thing that faith communities have to contribute to movements of social justice. I love the Hebrews text, “Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” My paraphrase is that hope means believing in spite of the evidence, and then watching the evidence change.

The evidence doesn’t look good right now, and people are afraid all over the world, with good reason. Donald Trump is a very dangerous man. And yet Donald Trump doesn’t have the last word. God has the last word, and people of God have to live as if we believe that God has the last word.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

This story originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of The Observer with the title “Interview with Jim Wallis.”