On Jan. 7, 2015, two masked gunmen forced their way into the Paris offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and murdered 10 journalists while shouting jihadist slogans. The attack was payback for caricatures of the prophet Muhammad the magazine had published. Two police officers would also die before the gunmen — brothers with links to al-Qaida of the Arabian Peninsula — were killed in a shootout with police.

The Charlie Hebdo attacks were followed by a hostage-taking in a kosher supermarket that left four men dead. Twenty-four hours later, a police officer was murdered in the Paris suburb of Montrouge.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, tens of thousands of people, many carrying placards that read “Je suis Charlie,” took to the streets in cities across France to show their solidarity with the victims. The French government raised its terror alert to the highest level, deployed soldiers throughout the country and rushed sweeping new surveillance measures into law.

At the time, it was hard to imagine how the violence in Paris could have repercussions for The United Church of Canada, headquartered 6,000 kilometres away in Toronto. Yet the Charlie Hebdo massacre helped to set in motion a chain of events that could culminate in the firing of one of the church’s most prominent — and controversial — ministers, and trigger a potentially divisive debate about what clergy and members in the 91-year-old denomination are expected to believe today.

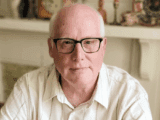

It all began with a prayer. The day after the attacks, the church posted a message on its website from then-moderator Very Rev. Gary Paterson, praying for “all affected by the Paris shooting.” Posting it was nothing out of the ordinary: disturbing or tragic world events often prompt an official response from the United Church. “Gracious God,” the prayer began, “by the light of faith, lead us to seek comfort, compassion, and peace, in the face of escalating violence around the world.”

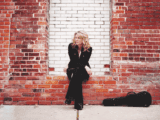

What was unusual about the prayer was the response it elicited from one of Paterson’s fellow ministers. Rev. Gretta Vosper, a minister at Toronto’s West Hill United who is also an author, speaker, blogger and — for the past several years — a self-described atheist, quickly weighed in online with an open letter to Paterson. She questioned his reference to “a supernatural being whose purposes can be divined” and called it a belief that “has led to innumerable tragedies throughout the timeline of human history and will continue to do so until it fades from our ravaged memory.”

Having a supernatural being at the centre of the church’s moral framework, Vosper wrote, means “we allow others to make the same claim and must defend their right to do so even if their choices and acts are radically different from our own.” In other words, Christians who confer divine authority on their God open the door to Islamic terrorists who can do the same with theirs.

“I urge you to lead our church toward freedom from such idolatrous belief,” the letter continued. It concluded, “Now is the time to speak clearly and bravely.”

Calling on a church to free itself from religion may stretch logic. Challenging the United Church’s elected spiritual leader over a routine public prayer certainly stretched the patience of the church leadership and many of its members and clergy — especially since it drew more media attention than the prayer itself. The buzz was hardly flattering. Writing in the Vancouver Sun, spirituality and ethics columnist Douglas Todd wondered if it wasn’t “a little gauche” for a minister to disparage believing in God from a Christian pulpit. The Winnipeg Free Press echoed the sentiment with a column headlined, “Atheist minister preaches hypocrisy.”

While her response to Paterson’s prayer was surely a tipping point, Vosper was already a thorn in the side of the United Church establishment. She blogs prolifically on her own website; her Twitter account states she’s dedicated to “Irritating the church into the 21st century.” Yet she considers herself a bona fide product of the United Church, crediting its Sunday schools and critical approaches to scripture and theology in its liberal seminaries with nurturing her beliefs — or lack thereof.

Born in Kingston, Ont., in 1958, Vosper was baptized at Sydenham Street United. As a Sunday school student, she was introduced to the New Curriculum — the United Church’s cutting-edge and controversial education resource for children and adults, which encouraged biblical questioning and interpretation. After earning an undergraduate degree at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick and starting a family, she moved back to Kingston in 1986, entering theological school at Queen’s University as a single mother. Ordained in 1993, she began her ministry in Toronto as part of a clergy couple before being called to West Hill United in 1997.

She now says she mouthed the words of traditional prayers, hymns and scripture without really believing in them. In 2001 — in what she calls her “de-constructing God sermon” — she told her congregation she no longer believed in God. She was ready for a showdown, but it never happened, not then anyway. Many of the parishioners at West Hill had already been studying progressive theologians such as Bishop John Shelby Spong, Tom Harpur and Marcus Borg.

‘I know no proof of God beyond personal experience, and I cannot acknowledge that proof as substantial.’

In 2004, Vosper spearheaded the founding of the Canadian Centre for Progressive Christianity, and in 2008, she published the Canadian bestseller With Or Without God: Why the Way We Live is More Important Than What We Believe. It clarified her disbelief in a supernatural God, stating: “I know no proof of God beyond personal experience, and I cannot acknowledge that proof as substantial.”

That same year, Vosper stopped using the Lord’s Prayer in Sunday services. That proved too much for some of the people in the congregation. As many as half of them left, most joining neighbouring United Church congregations. Those who stayed slowly rebuilt the church, adopting an increasingly unorthodox theology.

Currently, West Hill’s regularly updated vision statement reads, “With roots in the Judeo-Christian tradition, we embrace theists, agnostics and atheists.” There’s no mention of God or Jesus, but the statement cites “love as our supreme value, understanding love to mean the choice to act responsibly with justice, compassion, integrity, courage and forgiveness.” Scripture isn’t mentioned either, but the congregation makes it clear that “we consider no text, tradition, organization or person to be inherently authoritative, assessing all resources on their own merit.”

John DiPede, a longtime member of the congregation, elaborates: “We’ve always said that we don’t think anybody can come into West Hill and . . . feel uncomfortable about what we do. They may find discomfort in what we don’t say. . . . But all that we do talk about has a values base. And that’s common not just to us, to the Christian religion, but to all of humanity.”

On Sundays, the congregation gathers in a sanctuary where rainbow-coloured streamers obscure a large cross. Movable chairs, couches and easy chairs replace pews along one side. It feels more like an upbeat, musical kitchen party than a church.

Visitors are welcomed warmly. There’s an opening song, greeting time (much like passing the peace in other congregations), readings (rarely from the Bible), at least three more songs (familiar melodies, with new secular lyrics), perspectives (replacing a sermon), sharing time and, instead of the Lord’s Prayer, words of commitment written by Vosper and her spouse, Scott Kearns, who’s also the music leader.

The congregation seems happy. Needless to say, however, not everyone approves of what goes on at West Hill United. A 2011 Observer article on so-called post-theistic congregations, in which West Hill figured prominently, triggered a torrent of angry letters to the editor. “These post-theistic congregations have turned their places of worship into little more than coffeehouses for self-centred conversations,” wrote one reader. Another chimed in: “I have come to the conclusion that the United Church has finally and totally lost it.”

Undeterred by such criticism — and some that was frequently harsher — Vosper published a second book, Amen: What Prayer Can Mean in a World Beyond Belief, in 2012 and continued to raise her profile through her blogs, media appearances and speaking engagements. By 2013, her website identified her as “Minister, Author, Atheist.”

The new label made little difference to her congregation, but West Hill United member Kelly Greaves acknowledges that the word atheist is likely “what freaked everybody out.”

Vosper was not the only non-believing minister to step into the public spotlight. In 2013, retired pastor, United Church television host and two-time moderator nominee Ken Gallinger wrote that he no longer believed in traditional notions of God, was disillusioned by the institutional church and gave up his minister’s credentials. In late 2014, Bob Ripley of London, Ont., a retired minister who had led the United Church’s largest congregation, came out in a book and syndicated newspaper column as a born-again atheist. After being swiftly challenged by an official of London Conference, he too gave up his status as a minister.

A few months before the Charlie Hebdo attacks, West Hill United launched a satellite ministry in Mississauga, Ont. There was talk of another satellite ministry in downtown Toronto. By the time she challenged the moderator’s prayer, Vosper was well-known as the “atheist minister.” And she was squarely on the radar of the General Council office, where supporting the moderator is not only part of the culture but also a responsibility.

Shortly after Vosper posted her open letter, semi-retired United Church minister and blogger Rev. David Ewart of Vancouver wrote that Vosper should “take the steps to leave the United Church.” Ewart called her ideas about God “juvenile and unbelievable.”

In mid-March, Vosper was the phone-in guest on a London, Ont., talk-radio show. Host Andy Oudman expressed outrage that an atheist could be allowed to work as a minister, berating Vosper before eventually hanging up on her. She was nonplussed: she’d been object of similar derision during six years as a guest panellist on the Culture Wars segment of John Oakley’s Toronto talk-radio show.

But Oudman wasn’t finished. He reached London Conference executive secretary Rev. Cheryl-Ann Stadelbauer-Sampa, asking her whether anything could be done about Vosper. If anything could, she responded, it had to be done by Toronto Conference.

A few weeks later, Toronto Conference’s Executive and its executive secretary, Rev. David Allen, took action.

In early April, the board of downtown Toronto’s Metropolitan United — once dubbed “the cathedral of Canadian Methodism” — had written to Allen to ask about “West Hill United’s atheistic/post-theistic beliefs that are in direct contradiction to our creed and profession of faith and yet appear to be tolerated and permitted to propagate.” Signed by board chair Vera Taylor, who cited concerns about addressing church beliefs with potential new members, the letter spoke of “an abdication of core faith and of oversight.” Taylor’s letter urged Allen to act: “This is a time for courage and coherence!”

Until then, conventional wisdom was that Vosper, however unpalatable she might be to many, was untouchable under United Church rules that put the oversight of congregations and ministers in the hands of Presbyteries. Those rules say ministers can only be dismissed for insubordination, criminal or other misconduct, or ineffectiveness. As few as 10 members of Vosper’s congregation could spark a review of her ministry, but none ever came forward, so Presbytery could not accuse her of being ineffective.

However, in 2013, under a pilot project aimed at streamlining personnel processes, Toronto Conference took charge of the oversight and discipline of ministers within its boundaries.

With a mandate from the Conference Executive to look into ways to deal with Vosper, Allen asked General Council general secretary Nora Sanders for a ruling on whether the West Hill United minister could be asked to revisit her ordination vows with the Toronto Conference interview committee. The committee, and others like it across the church, usually evaluates the suitability of candidates hoping to be ordained, commissioned or admitted into ministry. The committee has to decide whether the candidates are in essential agreement with church doctrine and policies, and are able to respond positively to traditional vows. The first of those vows asks: “Do you believe in God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. . . .”

Neither the Toronto Conference committee nor any other church body had ever asked a minister to revisit vows to determine if that person was still suitable for ministry. In early May, Sanders ruled that Conference could do just that.

If found unsuitable, Sanders ruled, Vosper could be deemed ineffective and be removed from her job at West Hill United.

Sanders’ ruling made no mention of the concept of “essential agreement,” which is enshrined in the Basis of Union, the church’s founding document. The concept helped to pave the way for the creation of The United Church of Canada in 1925 and has allowed interview committees since then to approve new ministers who may not be able to answer all the traditional questions positively, but are in agreement with the essence of the faith and able to preach and teach its tenets. It has traditionally allowed ministers some theological leeway.

If church officials hoped the ruling would silence Vosper or lower her profile, news of the review had the opposite effect. Vosper was featured in daily newspapers and wire services across Canada and in respected international publications such as the Guardian and The Economist. A documentary about Vosper aired on the BBC World Service, she was interviewed on CBC’s The National and The Current, and profiled in The Walrus.

Vosper appealed Sanders’ ruling to the United Church’s judicial committee — the church’s court of last resort. By then, she had enlisted the services of high-profile Toronto lawyer Julian Falconer. The judicial committee eventually upheld Sanders’ ruling and declined to hear Vosper’s appeal. The review of her beliefs would go ahead.

So what does the United Church believe, anyway? In the late 1980s, when the denomination grappled over whether openly gay and lesbian people could become ordained or commissioned ministers, the debate hinged on one overriding question: was the Bible a literal guide (leaving LGBT candidates out in the cold) or could it be interpreted?

A General Council report adopted in 1992 confirmed that the Bible was neither “the authority” nor “an authority” but simply “foundational authority.” That decision could be seen as an opening for Vosper’s rejection of the Bible as “the authoritative word of God for all time.”

There was more debate on doctrine in 2009, when a proposal to the 40th General Council from Saskatchewan Conference sought to relegate the doctrine section of the Basis of Union to the status of a historic document. It led to a compromise that left the church’s founding Twenty Articles of Faith in place, along with the 1940 Statement of Faith, the well-loved 1968 New Creed (modified in 1980 and 1994) and the 2006 Song of Faith, as the accumulated church doctrine. But all those statements or standards were deemed secondary to scripture, which stood as the primary source of doctrine.

According to Rev. John Young, a former theology professor at Queen’s University, the main architect of the 2009 statement and now a General Council staff person, the compromise “suggests that we do agree that scripture is our primary authority. . . . That means that we are a denomination that wrestles, and wrestles seriously, with scripture.” But, on the other hand, until a scriptural debate works its way up to General Council where it might overpower the existing doctrinal statements, the various statements of faith stand as belief standards against which ministers or even members could be judged.

Vosper’s expensive but unsuccessful appeal of Sanders’ ruling argued that it unilaterally redefined “the church’s understanding of ministry,” and should have been put to a church-wide vote or remit. In her final submission, though, Sanders argued successfully that she simply made a “procedural ruling” and “any minister whose suitability is in question may be assessed using the review process.”

Others, however, worry about the precedent of allowing Conferences to challenge serving ministers on their beliefs. “How does a general secretary get to decide that we depart from the Basis of Union, which provides that provision of ‘in essential agreement’?” asks Rev. Bill Wall, a retired minister and former executive secretary of Saskatchewan Conference. “We’ve gone off on a tangent that was never authorized by General Council. We are in the wilderness, and it is extremely difficult to know where it’s going to lead.”

Fallout from Vosper’s review may someday bring a variety of theological and administrative issues back into the church courts for discussion. For now, though, the actions of General Council, its Executive and Toronto Conference have shut down possible avenues for discussing issues raised by the review, opting instead to stick with Sanders’ administrative solution.

The 2015 General Council very narrowly defeated a proposal from Toronto Conference — sparked by Vosper’s review and the theological issues involved — to review ministers’ vows in the Basis of Union “to ensure their continued relevance and effectiveness as we move forward in support of our ministry leaders.”

An almost identical proposal from Hamilton Conference, asking General Council’s theology and interchurch interfaith committee to do the review, was bumped off the General Council agenda due to time constraints, but came before the Executive at its autumn meeting in 2015. There, committee chair Rev. Daniel Hayward of Ingleside, Ont., said his committee could take on the task. But once again, the motion fell victim to a ticking clock.

When it came back before an online meeting of the Executive last April, the governance and agenda committee recommended that no action be taken: the theology committee was already too busy. Ironically, one of its tasks is to consider a new model for church membership where some members would not have to make a profession of faith. But there was no time to talk about ministers’ ordination vows.

Yet another chance to open up widespread discussion was lost a month later when Toronto Conference met in Midland, Ont., and debated a motion to reconsider its sub-Executive’s decision to go ahead with Vosper’s review. There were problems meeting quorum and confusion about what the motion meant. Eventually, the secret-ballot vote was 100-57 against reconsidering the review. Vosper’s supporters went home with fading hopes of further dialogue but aware that more than one-third of those who cast a vote seemed willing to leave the atheist in her pulpit.

Vosper is ‘not suitable to continue in ordained ministry because she does not believe in God, Jesus Christ or the Holy Spirit’

Vosper and two of her lawyers met with the Toronto Conference interview committee late last June. In the end, the review did in fact evaluate and rule on the question of essential agreement.

The majority of the Conference’s 24-member committee was not swayed by Vosper’s written and verbal answers to the ordination questions and doctrinal issues, concluding that Vosper is “not suitable to continue in ordained ministry because she does not believe in God, Jesus Christ or the Holy Spirit” and “does not recognize the primacy of Scripture, . . . will not conduct the sacraments and . . . is no longer in essential agreement with the statement of doctrine of The United Church of Canada.”

Along with its majority decision, the committee added a minority report from four members who felt that Vosper is suitable to continue in ministry. They pointed out that the church’s doctrine continues to evolve and that “many ministers and lay persons share Ms. Vosper’s belief in a non-theist God.” The minority report implies those beliefs could fit into the church’s most recent doctrinal statement, A Song of Faith, which refers to “God of Holy Mystery, beyond complete knowledge, above perfect description.”

Toronto Conference’s sub-Executive officially received the interview committee report on a sunny mid-September morning, and then held a three-hour session to hear from Vosper, her lawyer, members of her congregation and supporters from other congregations in the Toronto area and Ottawa, plus Toronto Southeast Presbytery.

Vosper appealed to the sub-Executive’s spirit of generosity, while her congregation attested to the strength of her ministry as an indication of her suitability. Lawyer Falconer called moving to a formal hearing that would decide his client’s fate “a huge mistake” and said Conference should put the review on hold for a year in favour of a structured dialogue or debate.

At that point, though, debate was little more than a faint hope. Still, the sub-Executive took almost a week to decide to follow the interview committee’s recommendation and to ask General Council to schedule a formal hearing. With a hearing panel chosen by the judicial committee, and likely to include people with secular judicial experience, Vosper’s removal from the ministry seems increasingly probable.

The review of Vosper’s suitability is probably the closest The United Church of Canada has ever come to holding a heresy trial, but there have been attempts in the past.

In 1979, Toronto South Presbytery tried to charge the late Rev. Clifford Elliott with heresy after he placed a controversial statue called Crucified Woman in his church; the effort failed. In 1997, early in his term as moderator, Very Rev. Bill Phipps declared that he did not believe Jesus was divine. A petition to have him removed from office was circulated, without effect. Both cases sparked widespread dialogue about the nature of God today. But the church’s choice of tactics in dealing with Vosper may alter the way it deals with such challenges in the future.

A Toronto Conference press release insisted “that a clear answer was required” in the Vosper matter. But it also expressed “sadness” over the “vitriol” aimed at both the Conference and Vosper. While still placing Vosper outside the boundaries of church beliefs, it said, “The sub-Executive hopes for respectful discussion that allows people to explore and share their own faith and to hear from others.”

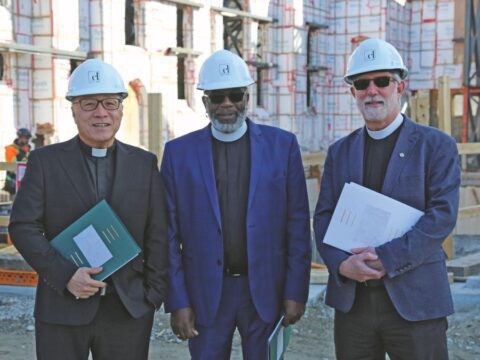

In an open letter to the United Church, Moderator Rt. Rev. Jordan Cantwell said she recognizes the tension between “our faith in God” and “our commitment to being an open and inclusive church,” but nevertheless pointed out that “faith in the triune God” is clearly part of church doctrine. Cantwell won’t defend or criticize Toronto Conference’s decision on Vosper or comment on Vosper’s ministry. Nora Sanders also declined to comment.

Members of Vosper’s congregation seem more disappointed than angry at the outcome. Dana Wilson-Li, past chair of West Hill’s board and a member of the committee that initially called Vosper, says, “The United Church that I’ve known all my life would have said, ‘Yes, let’s have a conversation about this.’ But instead they went to discipline.”

Church officials say it could be months before a formal hearing decides Vosper’s future. For her part, Vosper says she will continue to oppose efforts to remove her, but she’s acting more on principle than out of a belief that she can somehow keep her job. She was clearly downcast after the Toronto Conference interview committee found her “not suitable” for continued ministry. “I was not surprised,” she said shortly afterward, “but at the same time, the day was filled with grief because it seemed to me the indication that I really needed to give up the notion that this is my United Church anymore. It is not.”

Whatever the final outcome of the disciplinary action, the church will have to deal with divisions the controversy has opened.

Louise Lawrie and her husband, Mike, regularly drive 125 kilometres from their home in Cambridge, Ont., to attend services at West Hill United. Lawrie was one of Vosper’s supporters gathered outside the Toronto Conference office on the day of her review. “I feel criticized by my church because I have chosen to explore my faith,” she said.

Another gauge of support for Vosper came in a petition launched by parishioners at Southminster-Steinhauer United in Edmonton, urging Toronto Conference’s sub-Executive to reject its interview committee’s recommendations. In less than a week, the petition had gathered more than 1,100 signatures.

On the other side of the Vosper divide, though, are countless United Church people who readily profess faith in God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit, and can’t see how anyone calling themselves an atheist can remain a church minister.

According to Reginald Bibby, the University of Lethbridge sociologist who has studied the United Church widely, research suggests “that to the extent religious leaders — including United Church leaders — don’t believe in God, they are in a very lonely position.” A national survey Bibby conducted with Angus Reid in 2015 showed that 62 percent of “people who identify with the United Church” believe in God, while 30 percent call themselves agnostic and eight percent say they are atheist. But among people who attend services at least monthly, belief in God goes up to 98 percent.

Even so, Vosper remains the highest-profile United Church minister on the planet — a fact that surely irks the church leadership, many other ministers and tradition-minded members. And she continues to garner international media attention; the Washington Post weighed in with an article earlier this fall.

Whether Vosper will maintain her profile if she loses her United Church pulpit remains to be seen. If she is de-frocked, the West Hill pastoral charge — as an entity and a property — will remain within the United Church. It cannot legally part company with the denomination.

The bigger question for West Hill is whether the people in the pews, Vosper’s loyal flock, will follow her if she ends up elsewhere. Last February, there was a hint that they were thinking of options beyond the status quo at West Hill: the congregation voted to affiliate with Oasis, a small U.S.-based network of freethinking secular communities begun in 2012 by a non-believing former pastor. At the time, the West Hill congregation announced plans to launch an Oasis community in Toronto.

Skimming through the Oasis website, you can’t help but notice that the network’s core values — reality is known through reason; meaning comes from making a difference; people are more important than beliefs — could have been written by Vosper herself.

This story originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of The Observer with the title ‘Unsuitable.’