Getting in the mood to pray normally means slipping on my comfy pants and steeping a bag of ginger tea. It definitely doesn’t involve being inserted into a claustrophobia-inducing SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) machine. Or watching Lugol’s solution snake into my veins. Or tracking a scanner as it beeps and swirls around my head while I remain poker still for nearly an hour. But for one day in the spring of 2015 — just prior to a weeklong silent retreat — that’s what getting ready to pray required.

The SPECT scan was one test among a half-dozen to which my brain and the brains of 13 other participants were subjected over the course of about eight hours. These cranial calisthenics were part of a groundbreaking study on the neurophysiological impact of a spiritual retreat, conducted by Dr. Andrew Newberg, author of eight books and the director of research at the Jefferson Myrna Brind Center of Integrative Medicine in Philadelphia.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The first time I spoke to Newberg about his research over the phone, he enthusiastically described the goal of his next pioneering study: “So far, studies have focused on short-term psychological changes while praying. I want to look at the longer-term impact of a retreat.” Specifically, Newberg told me he aimed to discover how a spiritual retreat affects dopamine and serotonin levels and if it changes the way the brain operates. “I’m looking for study participants,” he said. “Are you interested?”

Are you kidding?

A few months later, I drive over the flat, sparsely treed landscape of upstate New York, through the mountain ranges and the Lehigh Valley tunnel, descend on downtown Philadelphia, and finally arrive at the Myrna Brind Center, a skip from where Rocky Balboa famously leapt up the stairs of the art museum. Newberg takes long strides toward me, bounding energetically across the floor. He’s younger than I imagined, and immediately likable. “Call me Andy,” he says with a broad smile. I’ll later learn he’s as capable of rattling off hockey statistics as scientific terms. We step into his office, and he goes over the waiver, explaining that he’ll do a full day of tests now and then again in a few weeks immediately following the completion of the seven-day silent retreat at the Jesuit Center in scenic Wernersville, Pa., a 120-kilometre drive into the countryside.

This isn’t the first time that spiritual practice has occupied a lab. Since the early 1990s, neurologists have been studying the effects of prayer, cataloguing benefits: lower anxiety and depression, a stronger immune system, more capacity to absorb and maintain information, and a higher pain tolerance.

Newberg has been instrumental in mapping the brain on prayer, uncovering the parts that prayer changes: the frontal lobes, which help focus attention; the parietal lobes, which take in sensory information, orient us in the world and give us a sense of ourselves; and, depending on the kind of prayer, the language, visualization, emotion and motor centres, too.

Thanks to a $200,000 grant from the Fetzer Institute, a Michigan-based foundation, my pre-retreat brain is examined; after a couple of weeks, I will circle back to Pennsylvania for the post-retreat portion of the experiment. I’m more nervous about the retreat than I am about being a lab rat; being silent for a week is going to be a challenge.

Entering the Jesuit Center, I walk past a row of Muskoka chairs lined up under a vaulted limestone archway. The chairs look out over an idyllic panorama of undulating hills dotted with maples. In the distance, an enormous weeping beech tree graces a labyrinth and gazebo. A pond rippling with well-fed koi fish waits around the bend.

Retreatants stroll the 97-hectare grounds, heads bowed in silence; as the week passes, they become strangely familiar, not by a perfunctory exchange of what they do for a living or even their deeper life stories, but by their physicality — their gaits, their dining choices, their exercise habits. It’s a peculiar way to get acquainted. Contemplation, prayers, naps and long walks fill the space between the scheduled obligations: meal times, a daily hour-long meeting with a spiritual director and eucharist services at noon.

It takes me four days to settle in; the first three days, I am edgy, unhappy and can’t put my finger on why. I sleep almost constantly: fatigue, a revelation. I fantasize about ditching sessions with my spiritual director, a sharp, soft-spoken woman, who eventually helps focus my days.

When I register surprise that as a card-carrying Protestant, I’m drawn to the crucifix, she suggests that I ask God what God wants to reveal to me through it. As the week unfolds, I delve into suffering, betrayal, relinquishing control and what it means to surrender. I spend luxurious hours staring at crucifixes, intently gazing at Jesus dangling gracefully in front of the cross like an emaciated ballet dancer. His loincloth knotted just so. Eyes closed. Wistful. Contemplative. Eventually, it dawns on me that the portrayals are not about denying or overcoming suffering but about finding peace in the midst of it. I drill into the suffering in my life, looking for peace in the places of struggle. This contemplative work is excruciating.

Later, a staffperson at the retreat centre tells me that the centre dissuades new retreatants from doing 30-day silent retreats because of the risk of mental breakdown. It’s an important caution. Being silent for a week isn’t everyone’s idea of a spiritual picnic. For some individuals, certain practices might do more harm than good. Science has yet to help us separate the wheat from the chaff.

Newberg learned the value of meditation early on. The summer between university and medical school set the trajectory of his career in neurotheology, including this study. “I had taken comparative religion courses in college and spent that whole summer meditating on the big question: how do we understand reality?” he says. “I wanted to look at things and decide whether I could know them or not, and if I couldn’t, then I would say, ‘Well, this is something that has to go into a realm of doubt.’” The deeper Newberg retreated into what he could know, the more he doubted. “In the end, I felt an infinite doubt. It wasn’t a bad experience; it was peaceful. I kind of surrendered to it. It had a spiritual element.”

I turn a mental corner halfway through the week when I decide to draw; putting a pencil to paper helps me feel more me.

After the fourth day, I feel my stress recede. Serenity sets in on day five. On day six, feelings of connection with God blossom. On day seven, I am disappointed to see the week end.

Leaving the Jesuit Center, I feel lighter, less anxious and more hopeful — convinced I should retreat again. On the heels of so much silence, the traffic noise and car horns on the drive back to the Myrna Brind Center in Philadelphia are almost unbearable. I arrive to another marathon of tests, including filling out a battery of psychospiritual forms designed to examine the nooks and crannies of my well-being.

Like all the other subjects, I report feeling more physically healthy, less tired, less tense and mildly less depressed and anxious after the retreat. Not surprisingly, across the board, all of us testify to feeling more spiritual and religious. Neurological scans back up the anecdotal evidence.

But not in the way Newberg expected.

Newberg is in the preliminary stages of analyzing the fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) data he collected in the study, but he already sees post-retreat changes — new parts of the brain appear to be affected, and there are changes in brain connectivity. “The best analogy I can think of is highways. [The retreat doesn’t] lay down new highways in the brain but changes the number of cars it sends down. It changes the brain’s functional connectivity,” he explains. “We can now see that more highways are involved than we’ve seen before, and have a better sense of the traffic patterns.”

He has completed the analysis of the SPECT data — and this is where the surprise comes in. Newberg anticipated seeing higher levels of dopamine and serotonin, the brain’s feel-good chemicals. Dopamine is responsible for happy feelings of love, joy and pleasure. Serotonin helps to regulate mood, irritability, impulse and memory. Yet while everyone reported feeling great after the retreat, Newberg didn’t find more dopamine and serotonin.

In fact, he found less. Overall, there was a five to 10 percent decrease in serotonin and dopamine transporters, which remove the neurotransmitters. It sounds like a drop in the bucket, but it’s significant given the brain’s delicate chemistry.

Enter the cocaine effect: “Cocaine actually blocks the dopamine transporter, so you get this sudden elevation in your brain, and that’s associated with the euphoric high,” explains Newberg. By directly lowering the amount of transporter, less dopamine is carried away, resulting in a greater rush. “What I think is going on here is that [a spiritual retreat] potentiates the brain’s ability to have this kind of experience,” he says. In other words, the spiritual retreat neurologically primes us to feel good.

“By praying repetitively or doing it in a concentrated form like a retreat, you are creating a brain state where the really big experiences — the enlightenment experiences, the mystical experiences — can happen,” he explains. “I think that’s maybe the best answer to what’s going on in this study and reflects what’s going on in these practices that we have never seen before.”

But exactly which aspects of the retreat stir up the neurological happy juice? Silence, switching off the cellphone, lounging outside, naps, conversations with the spiritual director, prayer? What if the study participants weren’t practising Christians? Would a newbie to spiritual practice register more whopping results?

Newberg states that the study elicits as many questions as answers: “One might wonder whether a Buddhist retreat, or simply going on a relaxing one-week vacation, would result in similar effects.” I swiftly volunteer to be a lab rat again should a vacation study ever come to pass. Preferably one that involves a beach in February.

More research dollars will be needed for Newberg to dig deeper — and he hopes his new study will help him to win another grant. While the study was small in size, the results are “remarkable,” he notes. “This is the first time anyone has shown a long-term consequence in the neurotransmitter area for any kind of spiritual practice or retreat.”

Could this study and others that follow lead to more spiritual and less pharmaceutical treatments for depression and anxiety? Or a surge in people signing up for silent retreats? It’s hard not to smell the money. A 2013 study published by the Global Wellness Institute estimates that wellness travel — including things like spa vacations, holistic cruises and spiritual hikes — is now a US$400-billion market, accounting for 14 percent of all tourism revenue. According to research hub IBISWorld, the meditation industry made over $1 billion in 2016.

Corporations are already offering their employees mindfulness training, and critics have charged that the bosses are more interested in keeping stressed-out workers on the job than in actually supporting their wellness. Will Newberg’s study prompt CEOs to send frazzled employees on extended silent retreats?

And there are deeper theological questions: If the primary goal of engaging in a spiritual practice is to inoculate ourselves against the 24-7 grind, are we more inclined to acquiesce to the hamster wheel rather than question why it exists at all? Are we simply anesthetizing ourselves to the issues that eat us alive? Is the modern mantra “to ground myself” the best answer to the question “Why pray?”

Surely the renewed attention science is paying to prayer and spiritual retreats has positive potential. The neuroscience in particular is affirming. I imagine the author of the book of James, who wrote, “The prayer of a righteous person has great power as it is working,” celebrating from the great beyond, arms raised in the air, dancing from foot to foot, yelling, “I told you so!”

Newberg chuckles as he recounts reactions to a prayer study he conducted with Franciscan nuns about 15 years ago. “Afterward, I showed them their brain scans, and they said, ‘Thank you Dr. Newberg. This is so exciting. It validates what we feel when we pray.’ Off they went feeling really good about seeing the changes in the brain scan. Then, when the paper came out, I got a call from the head of the local atheist society in Philadelphia, and he said, ‘We just wanted to thank you so much for showing that religion is nothing more than a manifestation of your brain function.’” Newberg muses, “Somewhere in my mind there is this cosmic balance — like, with one piece of data, I made a nun and an atheist happy.”

Characteristically, Newberg flashes between jocular and pragmatic in a heartbeat. “We always have to be cautious in how we interpret the information,” he says. “Clearly, what it shows is that by doing a practice or a program like this spiritual retreat, there are physiological effects. That’s what we can measure and show.” Is he concerned about what stakeholders will do with his research? “I can’t personally worry about how everyone takes the information. I hope that if people are going to use the research, they are going to use it in a way that ultimately benefits people rather than for the monetary benefits they could derive.”

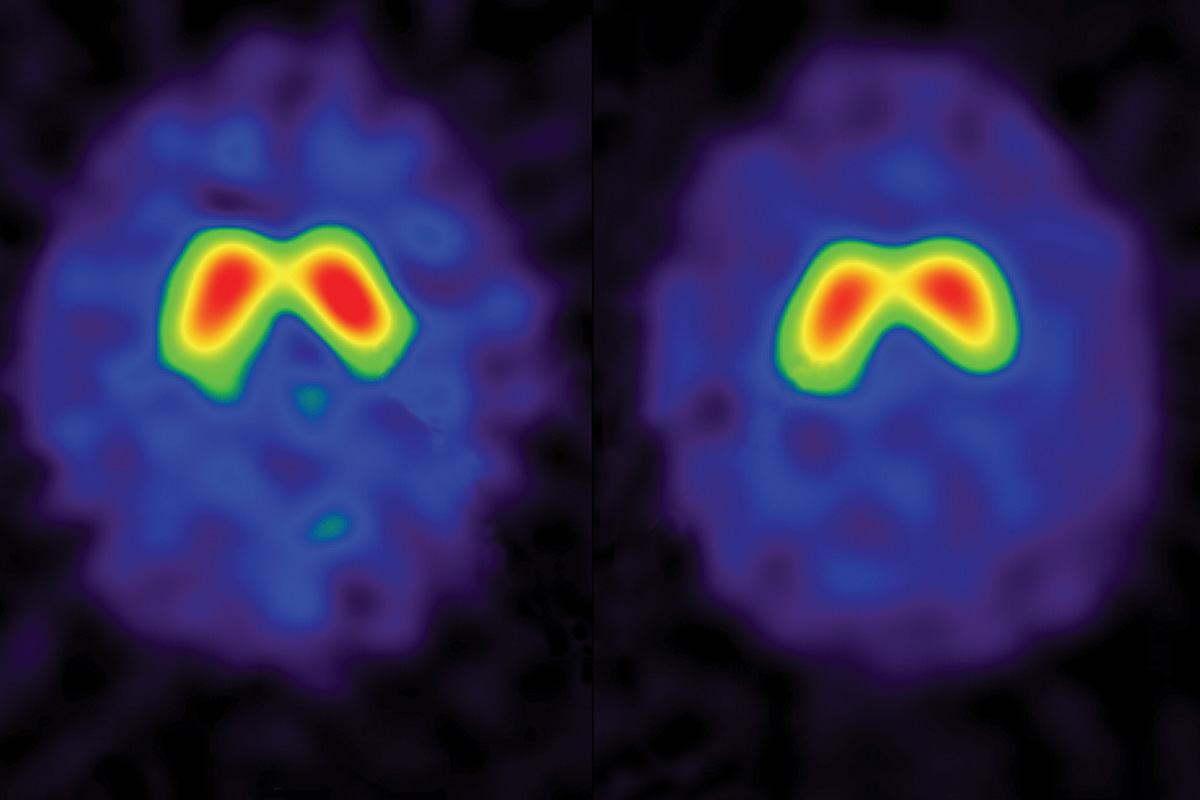

Over a year and a half after the study, Newberg sends me the images of my brain before and after the retreat. The basal ganglia area, a major dopamine centre, looks like a psychedelic mask. The colours reflect the amount of dopamine transporters. The intensity of transporters definitely shrank after the retreat. And this drop in transporters translates into happy feelings. Explains Newberg, “One interesting other way of thinking about it might be that the spiritual retreat acts a little like an SSRI [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor] antidepressant, since it seems to make the dopamine and serotonin transporter less active. The SSRI does it artificially by blocking it, and the retreat appears to do it more physiologically as the result of the meditation.” Riveting proof that the retreat made a difference. I can’t tear myself from the scans — an astonishing photo finish.

The images are the physical rendering of the calm I felt on the final day of the retreat — my footsteps echoing against the marble floors, the homey groupings of lounge chairs, the sunshine casting a halo in the cavernous space. On a side table, I found a small card titled “Daily Exercise in Spiritual Discernment” and tossed it into my purse. It’s been taped inside the drawer of my bedside table ever since. I practise the five spiritual movements it prescribes daily: Ask God for light to see as God sees; Thank God for specific blessings; Notice the movements toward God; Notice the movements away from God; Ask what I need for tomorrow.

This, for me, was a gem of the retreat: a simple but elegant take-home reminder that discernment is the core of the spiritual life — and the key to leveraging the extraordinary science of spirituality.

This story first appeared in The Observer’s March 2017 issue with the title “When neurons meet prayer.”