The Fugitive Slave Chapel has faced a demolition attempt, it’s difficult to maintain, there are mixed feelings about its potential relocation, and sustaining the relic will cost $300,000. Despite this, residents of London, Ont., are still working to restore the local Black community’s oldest surviving building at an open-air museum outside the city.

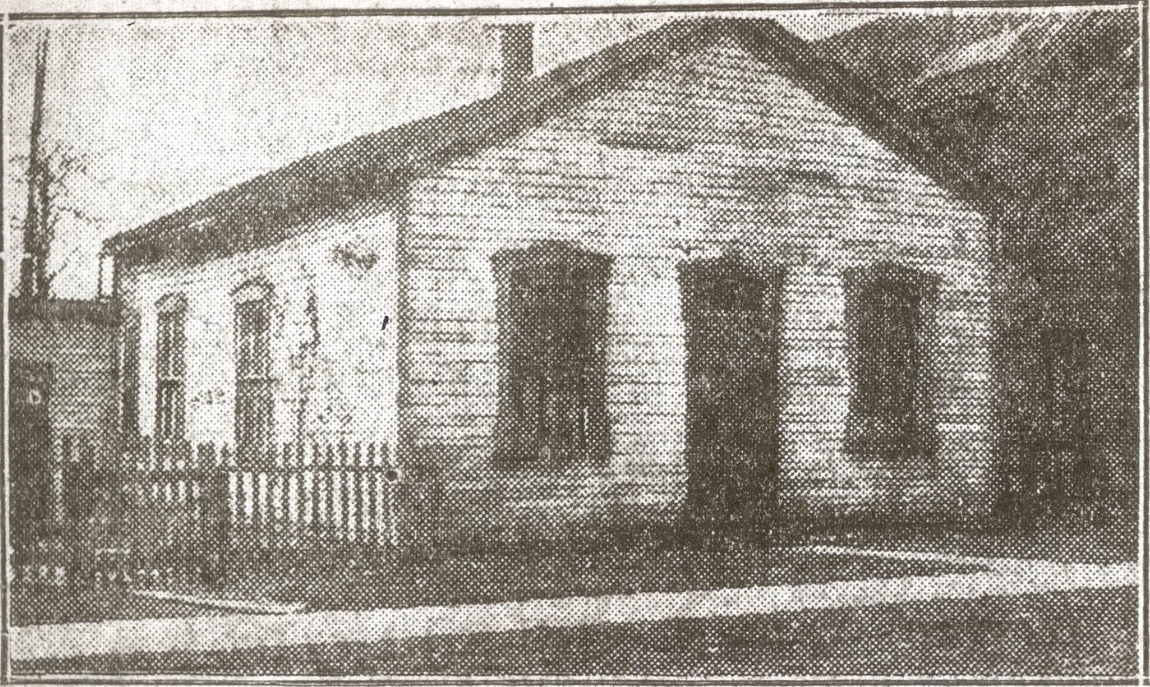

Initially located on Thames Street in London, the 19th-century chapel was one of the final points of the Underground Railroad. Former slaves who escaped the United States established a settlement and congregation there in 1847. The Fugitive Slave Chapel Preservation Project, a community-based effort to save the structure, wrote a proposal to Fanshawe Pioneer Village to preserve the chapel at their museum. Supporters want the chapel to become a learning centre, preserving the stories of Black freedom seekers who started their community.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“I think if people understand what that history means, then I think they will be more receptive to embracing that history,” says Natasha Henry, the president of the Ontario Black History Society. “People can understand that slavery is not who people were, but what what they were subjected to.”

Fanshawe Pioneer Village’s board of directors initially declined to add the Fugitive Slave Chapel to its museum.

With more than 30 buildings, the museum was not in the position to add extra building costs. But witnessing the community support through a virtual town hall of over 75 participants in September 2021 and letters of support from the Black History Coordinating Committee, the Black Lives Matter London group and the Congress of Black Women of Canada helped them reconsider the offer.

The museum accepted the building from its owner, Beth Emanuel Church, on the condition that at least $300,000 is raised so the deteriorating chapel can be restored before moving to its new home for renovations and preservation. Donations for their $300,000 fundraising goal currently sit at $50,000.

The Fanshawe Pioneer Village is fundraising among individual and corporate donors, the municipal government, and foundations. According to executive director Dawn Miskelly, the museum is also applying to match fund grant programs like the Canada Cultural Spaces Fund, which could potentially cover up to 50 percent of their expenses.

“We want to be part of the solution for the preservation of this building,” says Miskelly. “Our mission is to connect our communities by remembering, sharing, and celebrating local histories.”

While finding a new location for the chapel was a victory for some, the news was bittersweet to others.

“We have to be truthful and say we have mixed feelings about it. It’s always nice to have a building close to where it grew up,” says Genet Hodder, chair of the Fugitive Slave Chapel Preservation Project, which worked to move the church down the road to its current location when it faced demolition in 2013.

The museum is outside London, which is a drawback, Hodder says, because people need cars to access it. Despite the lack of public transportation, Hodder says there are “tremendous advantages” to the new plan.

Hilary Neary, a member of the Fugitive Slave Chapel Preservation Project, says she is moved by the church, having learned about congregants finding “solace and comfort” in the building despite their painful lives. “I can’t help but believe [it’s] reflected in the wood and the shingles and the windows and the doors of this building.”

The chapel was part of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first African-American denomination in the U.S. When the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 compelled Americans to capture runaway slaves escaping to Canada (then British North America) where slavery was banned through the Slavery Abolition Act in 1834, the newly freed Black community did not want their church associated with America. They separated from African-American Methodists and became the British Methodist Episcopal Church in 1856.

As more freed Black people came into Canada, the Fugitive Slave Chapel needed more space to fit its congregation. This led to the establishment of a new church between 1868 and 1871, Beth Emanuel Church, located on Grey Street, while the older building sat empty.

While researching the chapel’s history, Neary uncovered more about its community through letters from Rev. Lewis Champion Chambers, a missionary pastor from the American Missionary Association who led the church from 1860 to 1863. His letters detail how Black skilled labourers and farmers struggled to find work. In some cases, they experienced more prejudice in Canada than the United States, as many families from the southern states also migrated north to settle. Chambers also shared about the difficulties of segregated schools.

More on Broadview:

- By day, he was my dad. By night, he was the Padre of the Pubs.

- Website preserves Vancouver Japanese United history

- The Acadian roots of a curious Ontario landmark

Henry says this history corrects the often “misinformed” idea that Black people are new to London. “It also helps contextualize the long, entrench[ed] history of anti-Blackness in London.”

When the owner of the property where the chapel rested filed for demolition in 2013, community members rallied to save it. Beth Emanuel Church offered their property as a new home.

Community members raised money to hire an architect to help restore and repurpose the church, along with some financial support from the City of London. Its walls were replaced and pews removed, temporarily serving as a space for charitable outreach. Its relocation to Grey Street in 2014 was a testament to the city’s history as it rested in the Soho region, one of the two original Black communities in London.

“It was like a mother coming back to live with the daughter,” says Neary.

Several years later, the costs of maintaining the chapel became too burdensome for Beth Emanuel Church. The Fugitive Slave Chapel was on the verge of disappearing again until the museum became a solution.

Neary says Fanshawe Pioneer Village is the best possible place for the chapel to be preserved and become an education tool for visitors who want to learn about the past.

“Reading the words of people who’ve lived through difficult experiences can be a transforming event in somebody’s life,” she says. “I think that this building can be a very effective interpreter of a very important part of Canada’s history.”

With files from Ashley Okwuosa

***

Sherlyn Assam (she/her) is a freelance writer from Brampton, Ont.

This report on the Black Church in London has good information. I have been fascinated by a parallel story of Priceville near where my Perigoe ancestors settled, and also by the story of the BMEC in Toronto.