Every Sunday, the St. Lawrence Antique Market bustles with life in one of Toronto’s oldest neighbourhoods. Vendors display a colourful array of relics and artifacts from earlier eras for bargain hunters like me to dig through. You can find vintage typewriters, jade and platinum jewelry, art deco credenzas and davenports, vinyl records and all sorts of other knick-knacks and doodads from the past.

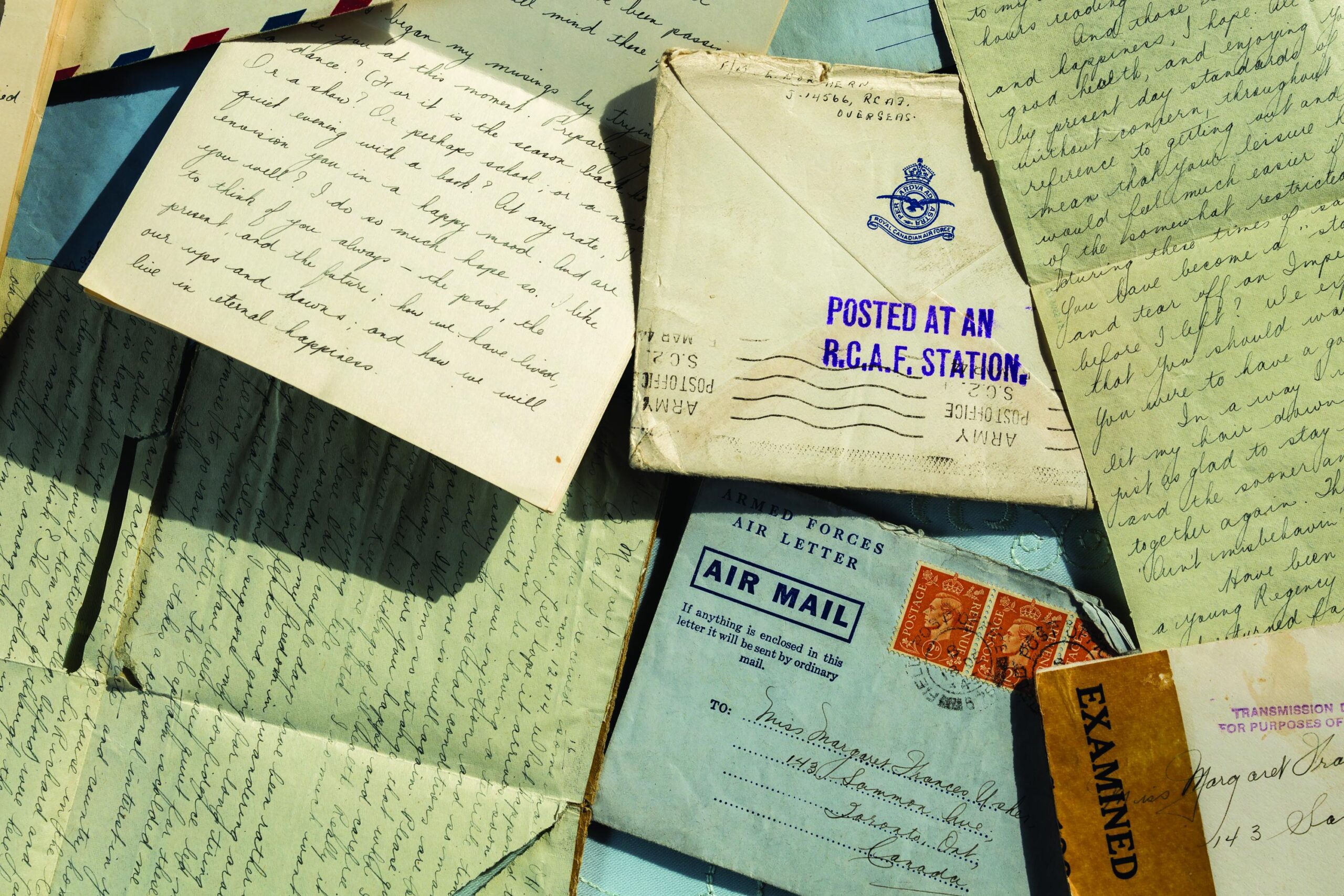

One Sunday late last year, I peeked into a cardboard box on the floor and found a stack of love letters tucked inside a Ziploc bag. They appeared to date between 1942 and 1944 and were written by someone named Edward Northern, who I learned was a flight lieutenant stationed overseas with the 420 Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Based out of Tholthorpe in Yorkshire, England, Edward Northern’s squadron was integral to the war effort, performing tactical bombing operations, many of them night raids, over Germany and occupied Europe. But Edward’s letters reveal a different side of him; they are penned lovingly to his sweetheart, Margaret Usher, who lived on Sammon Avenue in East York, in what is now part of Toronto.

I stood in the market and browsed through the letters. They were written on standard-issue RCAF stationery: a delicate robin’s egg blue adorned with the snowy owl crest of Edward’s squadron, each sheet folded upon itself to create an envelope. Most of the letters had been sliced open by censors and stamped to mark their approval.

As an avid collector of old love letters, I knew I had found something special. A voice inside my head kept saying that if I didn’t buy them, I would regret it. The vendor wanted $20 for the stack. I talked her down to $14. The 12 letters would reveal the ache of young love torn apart by war and the difficulty of truly knowing someone through the traces they leave behind.

Over a period of about two years, Edward sends Margaret regular letters of love and affection. “The Sunday afternoon in your kitchen . . . when we confessed our love was the greatest day for me,” he writes in elegant cursive. “How anyone could be that kind to me was almost too much to bear. . . . I do need your love. The assurance that it is always there gives me so much, much more confidence in myself. And it gives me something worth fighting for.”

Margaret’s letters appear to buoy Edward’s spirits. In reply to one, he writes, “It made me happy. You seem to be well and content. That means a lot to me. . . . Don’t let the smile wear off. It will give us both hope and confidence, without which we are lost.” Later in the same letter, he asks, “Would you mind sending me a picture of you, dear? I have been wanting one for a long time, but was afraid of damaging it. Now I think everything will be fine for a picture of you.”

Edward insists on a greater frequency of letters and expresses unbridled joy upon receiving care packages. His delight reflects the widespread enthusiasm among soldiers for correspondence during the war. Historians have suggested that letters were almost as important as food in the lives of soldiers fighting overseas. Because they were so key in maintaining morale, writing letters was one important way that families and friends were able to contribute to the war effort from home. Over the course of the Second World War, billions of pieces of mail crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

In his own letters back to Canada, Edward regales Margaret with tales of the war. He describes his companions, their late-night barracks shenanigans and the great feeling of being among a band of brothers. He shares the story of a bombardier climbing to the top of a statue of the Duke of Wellington and even tells Margaret when his rear gunner contracts a venereal disease during leave. He writes of the movies his squadron is treated to in the mess hall, like Big Shot starring Humphrey Bogart, wondering if Margaret has seen them as well. And he tells Margaret of the songs he hears on the wireless that remind him of her, including Bob Hope’s Two Sleepy People.

But Edward’s high spirits are quelled when the war harms his squadron. “Fred crashed in England and is still in hospital. John went missing a few weeks ago. Both really good lads,” he writes on Feb. 28, 1944. In the same letter, Edward describes his own brush with danger. “A little over a week ago I went on a raid with partially unserviceable oxygen equipment. The strain was too much, and, try as I might to overcome the effects, I just passed out over the target. However, I got back to England. Felt very ill for some days following; and when I tried to go on another show, the M.O. [medical officer] advised strongly against it. His argument was so convincing that I wound up in a hospital cot.”

Despite the deaths of his peers and his own injuries, Edward remains confident of his purpose in the war and enthusiastic about flying. “Deep-throated, guttural roars made me crane my neck to stare out the window as our huge air armada took to flight,” he writes from the hospital. “No one can tell just how many will return, yet each one grins as he goes out into the black of night — grins and is thrilled because he knows that his load is just one more step toward winning this great fight for freedom.”

Every letter is signed with a variation of “I love you dearly” or “Forever yours” or “With all my everlasting love,” and he even employs his French language skills once with “Mon cœur est toujours à toi” (my heart is always yours). A parade of Xs follows his signature, at one point taking the shape of the phrase “I LOVE YOU.”

How did Margaret feel about Edward’s ardent professions of love? When two letters from another man slipped out of the package, I began to wonder. Written at the same time as Edward’s, they were signed by a man named Casey. There is no last name and no return address. These letters are written with care and investment, but they lack the passion of Edward’s. Still, Margaret had kept Casey’s letters along with Edward’s. Had I stumbled upon a love triangle?

The last letter from Edward that I have in my possession is dated Feb. 28, 1944. The final words are “Keep those big brown eyes smiling. I love you.” What happened after that? Did Edward return and marry Margaret, as he said he hoped to?

I started to realize how little I knew about the people whose intimate lives I had been prying into, more than 70 years later. So I went to the library. As I scoured through historical records — census documents, voter rolls, city directories, passenger manifests, birth and death certificates, declassified military files and the genealogy website Ancestry — a fuller picture emerged. The Toronto District School Board lent me yearbooks from Edward’s high school, East York Collegiate, which he attended between 1931 and 1936. Edward’s letters say he met Margaret in 1934, when he would have been about 16, so I surmised they were high school sweethearts. I had detected a scholarly inclination in his letters, so cleanly written and polished, and Edward’s pre-war life, as revealed in his yearbook, corroborated this. Edward, in fact, edited the yearbook, played rugby, spoke French and knew rudimentary German. His graduating quote was from Shakespeare’s As You Like It: “Nay, I shall ne’er be ’ware of mine own wit till I break my shins ’gainst it.”

Edward’s declassified military file explains the sudden end to his letter writing. He flew into enemy skies on the night of April 30, 1944, and disappeared along with the rest of his squadron. While the bodies of some of his peers were found the next day, his never turned up, and he was later officially presumed dead. He was 26.

I found carbon copies of the mournful letters the RCAF sent to his mother on Toronto’s Woodbine Avenue. “I am fully aware that nothing I may say will lessen your great sorrow, but I would like to express to you and the members of your family my deepest sympathy,” wrote the RCAF casualties officer.

Tragically, Edward was scheduled for leave after he completed his last mission. Instead, he was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and his name was included along with 20,450 others on the Runnymede Memorial in England for Second World War airmen whose bodies were never recovered. His file also includes his official military portrait. With his square jaw and slicked hair, his pencil moustache and the glint of a mischievous humour in his eyes, he was painfully handsome.

I needed to know more. I searched through the Toronto city directories from the 1940s and found Margaret listed as living on Sammon Avenue with her family and employed as a fibre worker at the de Havilland airfield in what’s now north Toronto. By 1951, Casey Sterling is listed as living with Margaret in the house to which both suitors addressed their letters. Margaret takes Casey’s last name by 1953, and they move to their own home in Scarborough, now part of Toronto. I found voter records from the 1970s referring to a Wayne Sterling living at the same Scarborough address; I presumed he was their son.

These new details were illuminating, but I still felt removed from the real lives of Edward, Margaret and Casey. The traces our lives leave on paper are merely a shell, bare outlines often recorded at arbitrary moments and incapable of capturing the fullness of our experience. I had access to all of these facts, but none of their emotional impact.

After a bit of digging, I found Wayne Sterling on social media and I reached out, hoping he might fill in the details. We met for coffee in the north end of Toronto. He was a short, pleasant man, probably in his 60s. Finally, after researching the lives of these people for months on end, I was able to connect them to a living person. Sterling told me that his mother, Margaret, died in 2016 at the age of 96. His dad, Casey, had died long before that.

I told Sterling that I was researching the life of an RCAF officer who was a friend of his mother’s. Sterling asked if his name was Ed. “I can remember [Mom] talking way back about him.” Apparently, his mother said that if Edward hadn’t died, she would have married him. Beyond that, Sterling didn’t have much more to share. He didn’t know precisely how his mother and Edward met. He didn’t know if Casey and Edward knew each other. He couldn’t tell me if his mother loved both men at once. But that didn’t surprise me. How often do mothers reveal the secrets of their hearts to their sons?

Sterling did, however, share a story his mother had told him. Once, Edward had taken her up in an airplane at the de Havilland airfield. The plane was damaged with bullet holes, but he snuck her out in it anyway. Sterling told the story with giddy pride, showing that Edward’s memory, and the impact the young pilot had made on Margaret, were still alive in this family.

In the air over the de Havilland airfield that day, Edward joined together the two things he seems to have loved most: Margaret and flying. Maybe he thought he would fly with her again one day. Certainly, his letters carry that hope. On July 3, 1943, he wrote, “Remember when we were at the Uptown on those last few days before I left? The organ played, ‘We’ll Meet Again.’ . . . Believe me, we will.”

This story first appeared in The Observer’s November 2018 edition with the title “Forever Yours.”