The “creation versus evolution” controversy was heating up again. It was the 1980s, and I was a published doctoral student in late Victorian Darwinism and theology. I had researched Charles Darwin’s life from womb to tomb, studied his published work, his unpublished archives at Cambridge University, his scientific circle of friends and a ton of theological responses to his work. I was teaching the specialist course Darwin and Darwinism at the University of Toronto’s history of science institute.

And so I was invited to lecture biology professors of the faculty of zoology on “Darwin and the creationists.” The expectation, I suppose, was that I would keep Darwin on his pedestal and expose the religious fanatics for the ignorant dim-wits they were.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

I started with an analysis of the structure of The Origin of Species, noting the gaps in Darwin’s evidence and how they affected his argument. Murmurs in the audience grew louder as I described Darwin’s theological education and influences. From the 1820s through the 1840s, as he was developing his idea of natural selection, Darwin was a Christian who saw both evolution and design in nature, God’s creation. The Origin offered a scientific argument for how the Creator worked by means of natural laws.

By now the audience— professional evolutionists all, though none had actually read The Origin — were freaking out. Darwin some kind of design theorist? God forbid, some kind of creationist? I was heckled: “You’re wrong!” “Lies!” “Darwin was an atheist!” I quickly finished up, but not before slipping in the news that both creationists and evolutionists are guilty of misrepresenting Darwin to defend an ideological view of faith and science as mutually exclusive and antagonistic.

Afterward, one highly indignant professor followed me all the way across campus to my office, spittle flying. Red-faced, at times screaming, he told me I “must be wrong” about Darwin and creationists. “Evolution is real!” (No argument there.) “Darwin rejected God!” (Not so.) “Science proves there is no God!” (Not possible.)

So went my first close encounter with scientific fundamentalism.

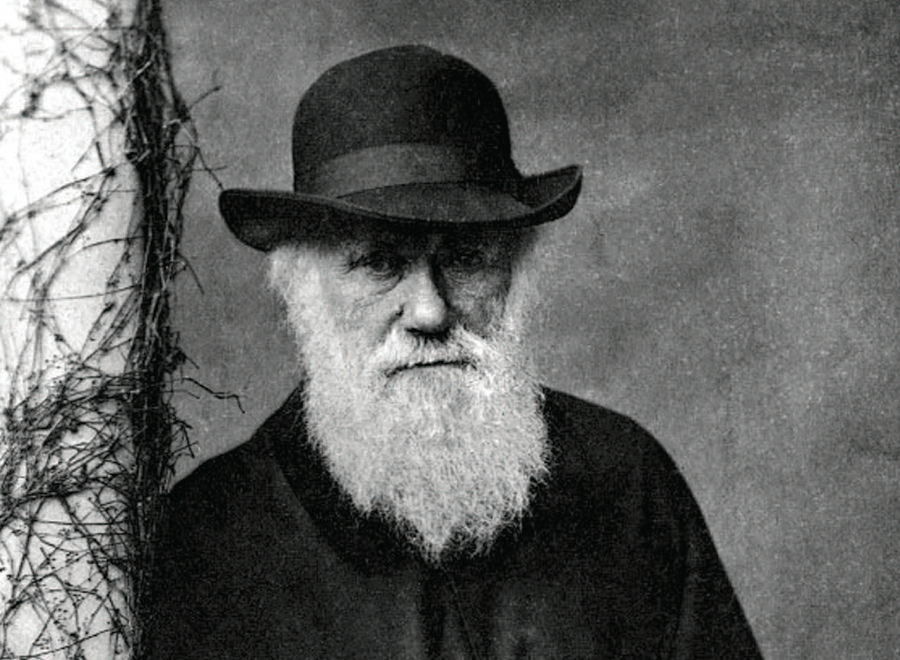

HISTORICALLY, DARWIN’S SCIENTIFIC IDEAS are perhaps the most important ever conceived and confirmed. Yet Darwin the man is shrouded in conflicting mythology. The actual narrative of his life, in particular his eventual turning away from orthodox Christianity, is not as neatly linear as either the evolutionists or creationists would have us believe. It’s considerably more interesting. Thanks to the work of many scholars, we can now peer into it through documents Darwin left behind, unpublished in his lifetime.

Evolution did play a part in Darwin’s eventual turning away from Christian belief. But more crucial to Darwin’s religious journey was the theological problem of suffering in a world created by a good God, and the deaths of loved ones.

Darwin was supposed to become a physician like his father and grandfather, but he wasn’t cut out for it. So he became an Anglican priest, a respectable vocation, which would allow him to continue his true passion, studying natural history. After reading books on theology and the Apostles’ Creed, assenting to the church’s Thirty-nine Articles of Religion and affirming the literal truth of every word in the Bible, Darwin went to Christ’s College, Cambridge, in 1828 to begin studies toward his BA in divinity.

At Cambridge, he cut classes and spent his time hunting, drinking and beetle collecting. But he also attended geology lectures and befriended Rev. John Henslow, a pastor and professor. Henslow taught him botany and recommended Darwin, after graduation, for the round-the-world voyage of HMS Beagle, where he would serve as the ship’s naturalist.

Darwin also mastered the work of Rev. William Paley, author of Evidences of Christianity and Natural Theology, who looked upon the natural order and saw evidence of God’s adaptive designs, both great and small.

Darwin set out aboard the Beagle in 1831, intending to be ordained and expecting to find new signs of God’s power and wisdom at work in creation. On Sundays, he attended shipboard worship services and read from his Greek New Testament. In his diary, he spoke of the Brazilian rainforest as a “temple” filled with the handiwork of “the God of Nature.” No one could witness such sublimity, he wrote, “without feeling that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body.” Yet, also in Brazil, he witnessed the horrors of slavery — an offence to his Christian ethics and to his belief that all humans constituted a single species with a common origin.

Gradually, Darwin’s reading, observations and experiences led him to doubt the literal accuracy of biblical narratives. He came to believe that miracles violated “the fixed laws of nature.” He found the Old Testament’s portrayal of God as “a revengeful tyrant” objectionable. By the time the Beagle finished her voyage in 1836, Darwin’s clerical-naturalist vocation had transmuted into that of a naturalist alone; but he was far from being an unbeliever.

On his return to England, he began to focus on the origin of species by natural, rather than supernatural, means and saw that characteristics such as eyes or wings could have evolved incrementally, without a designer. In 1838, while reading Rev. Thomas Malthus’s Essay on Population, he realized all organisms were continuously struggling to exist and reproduce in a world of limited resources. Those best suited to survive any given habitat would be selected by nature.

Those less fit would be eliminated. Here was a theory by which he could imagine new species, over time, descending with modifications from earlier ones.

Darwin slowly began to transfer the creative and providential powers of the Christian God to nature, or more precisely, to what he called his new “deity”: natural selection. The idea that God works through laws, not whims, did not diminish God, but “should exalt our notion of the power of the omniscient Creator,” he wrote in 1842. Like God’s own radar, natural selection swept over the world scrutinizing “every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving . . . all that is good.”

Darwin’s fateful turn away from orthodox Christianity came in 1851, more than a decade after he discovered the role of natural selection in evolution and eight years before he published The Origin. The catalyst was the death of his first and favourite daughter, Anne, who had just turned 10. Darwin had been by her bedside at a clinic in Malvern, Worcestershire, during her last weeks as she struggled with fever, vomiting and diarrhea. Throughout, he desperately held out home she would rebound. “I trust in God we are nearly safe….Poor dear little soul,” he wrote on Easter Monday to his devout wife, Emma, who was 250 km away at their home and too pregnant to travel.

Two days later, Annie was dead. Her funeral service was taken from the Book of Common Prayer, her gravestone engraved with “IHS,” the first three Greek letters of the name Jesus.

His tears gave way to angry grief. “We have lost the joy of our household and the solace of our old age,” he wrote. He idealized Annie as a perfect “little angel,” undeserving of any punishment in this life or the next. But he could no longer believe that her soul was in heaven. What kind of God could take away such a loving and beloved child?

Darwin was 42 at the time of Annie’s death, and it haunted him for the rest of his life. Later, in the private autobiography he prepared for his family between 1876 and 1881, he wrote bitterly that that he could “hardly see” how anyone could “wish Christianity to be true,” for if it were, the “plain language” of the Bible seems to claim that those “who do not believe, and this would include my father, brother and almost all my best friends, will be everlastingly punished. And this is a damnable doctrine.”

Yet while he rejected key doctrines of Christianity, including the divinity of Christ and the afterlife, he never fully rejected religion or the idea of God, the Creator who had designed the laws of nature Darwin so revered. He declared he had “no intention to write atheistically.” Nor would he ever. Indeed, Darwin invited his masterwork to be read theistically. A few examples: while the word “evolution” appears not once in the first edition of The Origin, “creation” and its variations appear more than 100 times.

Opposite the book’s title page Darwin supplied two theological epigraps. One affirmed that God created through nature’s laws, not special “interpositions” of power. The other urged study of both the Bible (“the book of God’s words”) and science (which reads nature, “the book of God’s works”). In the second edition published in 1860, Darwin added a third epigraph, this one from Bishop Joseph Butler’s Analogy of Revealed Religion, affirming that “what is natural as much requires and presupposes an intelligent agent to render it so…as what is supernatural or miraculous.” He also added a telling phrase, about life being originally breathed into the first creatures “by the Creator,” to the last sentence of the book.

Ironically, while the scientific community mainly rejected natural selection for decades, theologians from fundamentalists to liberals embraced it, believing that Darwin, far from having dispensed with God, had explained how God works. Asa Gray, a conservative Congregationalist and Harvard botanist, for example, wrote an essay called “Natural Selection Not Inconsistent with Natural Theology,” which Darwin proposed and had printed at his own expense.

Darwin stopped attending church after his father died, yet he played an active role in parish life. His children were baptized and confirmed at the parish church, where the family had both a pew and a plot. Darwin entrusted the education of his four younger sons to carefully chosen Anglican clergy. He maintained a lifelong friendship with the local vicar, supported the local church and five Sunday schools, and helped supervise church finances. Emma, like a good pastor’s wife, held family prayers on Sundays, took the children to services and dispensed food and medicine to the elderly, poor and sick. She also organized a drop-in centre/reading room for local workers as an alternative to the pub. She and Charles supported the work of evangelists who came to the village preaching temperance.

In a letter written three years before his death in 1882, Darwin declared he had never denied the existence of God, that one could certainly be both “an ardent theist and evolutionist.” But he really was no longer sure of such things. His theology, as he confided in an earlier letter, was “a simple muddle.”

Darwin was able to reconcile the power and glory of a good and loving God with nature’s cold indifference and manifest cruelty — the infamous and pitiless “survival of the fittest” — by viewing struggle, pain, suffering and death not as the direct will of God but as the result of the impersonal operation of universal laws. The process of evolution by means of natural selection was deadly and wasteful, and yet, as Darwin concluded in The Origin, it had a higher, nobler purpose. Higher species would evolve. The Creator — the God of scientific theism— lawfully drew good out of evil and progress out of pain.

Near the end of his life, Darwin thought it impossible to conceive that “this immense and wonderful universe” was “the result of blind chance or necessity.” No, it still seemed that the world had been willed into being. “I feel compelled to look to a First Cause having an intelligent mind in some degree analogous to that of man,” he wrote in his autobiography, “and I deserve to be called a Theist.” At the same time, Darwin believed that “the mystery of the beginning of all things” was simply unsolvable; and so he also declared, “I for one must be content to remain an agnostic.”

A few weeks before his death, Darwin came across a familiar letter that Emma had written to him just after their marriage in 1839, in which she expressed worries about the religious doubts that Charles had shared with her. It grieved her to think they might not be together eternally, and she urged him to reread Jesus’ farewell discourse to his disciples in John’s Gospel. At the end of the letter, he added in his own hand for his wife to read, “When I am dead, know that many times, I have kissed and cryed over this.”

Darwin was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. His friends wanted him in the national cathedral next to Isaac Newton. As always, different interests contended for a Darwin of their own construction. An atheist whom Darwin had rebuffed late in life soon published a tract claiming him for unbelief. Then, early in the next century, the legend of Darwin’s “deathbed conversion” spread like wildfire among evangelicals. Racists, capitalists, communists and Nazis all saw Darwin as “one of us.” Anti-evolutionary creationists saw him as a force of evil. And theologians of various stripes began a dialogue with Darwin that continues today, in which doctrines of creation and providence, sin and salvation, evil and eschatology are re-examined in light of our best knowledge of how the world works.

Two hundred years after his birth, 150 years after The Origin’s publication, we are still coming to terms with Darwin.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s November 2009 issue with the title “Rescuing Darwin.”