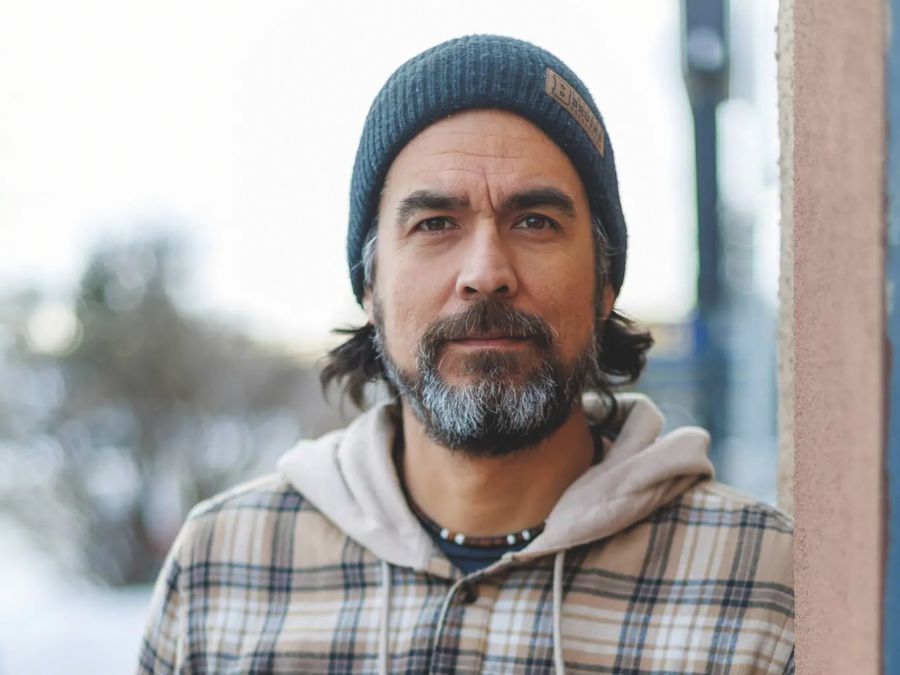

Award-winning Cree author David A. Robertson has long been at the forefront of Indigenous storytelling in Canada, using fiction, memoir and graphic novels to provoke necessary conversations about truth and reconciliation.

His latest book, 52 Ways to Reconcile: How to Walk with Indigenous People on the Path to Healing, is a practical guide to engaging with reconciliation all year long — one week at a time. Blending personal anecdotes, reflection and action-oriented suggestions, Robertson invites both settler and Indigenous readers to embark on a journey of understanding, relationship-building and change. In this conversation via Zoom from his home in Winnipeg, he speaks to Julie McGonegal about what reconciliation truly demands of us.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

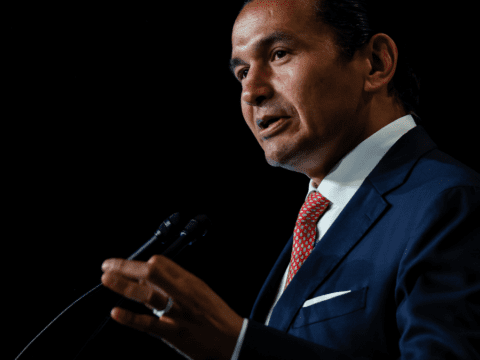

Julie McGonegal: What does reconciliation mean to you?

David A. Robertson: I think about reconciliation in two ways. One is from the perspective of the Indigenous community. My father and I used to talk about this often. Reconciliation in its truest form happens at the level of the Indigenous individual, family and community. Before colonialism, we had well-structured, healthy communities. Colonialism disrupted all of that. So now, the work is about healing. Within Indigenous communities, we need to mend relationships that were once strong. That, to me, is the purest form of reconciliation.

When people talk about reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canada, I struggle with that. There was never a good relationship to begin with. Instead of repairing something that was broken, we’re trying to build something that’s never existed: a healthy, respectful relationship grounded in understanding. That’s what reconciliation means to me.

It’s a conversation, an interaction. It’s about respecting and learning from one another to build something new together.

Reconciliation used to focus primarily on residential schools. That should always remain a cornerstone. But it has to encompass more — missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, the justice system, education, health care, the foster care system. We have a lot of learning to do. If you don’t understand what’s wrong, it’s hard to fix it.

“…have faith that the things you do today will make an impact tomorrow.”

JM: Where do we see the impacts of colonialism today?

DAR: The foster care system is still a big problem. It’s a colonial system. And the fact that over half the children in foster care are Indigenous — that’s an enormous number. It’s like a second residential school system.

You can’t say “Now we’re starting to heal” when trauma is still happening. We’re not even at a point where we can heal in a holistic way. It’s a long movement. It requires broad, consistent action — and it requires everybody.

JM: Do you worry that we’re losing momentum? Reconciliation was a buzzword 10 years ago. But now, with nationalism and sovereignty on the agenda, it feels like we’re moving into a different period.

DAR: When something becomes a buzzword, it leads to exhaustion and complacency. I want people to feel like what they do matters. That’s why I wrote this book: 52 Ways to Reconcile is meant to invite people in. It shows that this work is doable in small steps — and every step matters.

Some of the ideas are small, some are fun, some are more involved, but they’re all things anyone can do. Every action has an impact.

My dad used to say that change takes more time than we have. He believed that if he did it right, he wouldn’t see the impact in his lifetime. So you have to take the long view and have faith that the things you do today will make an impact tomorrow.

Complacency is a problem. You see it with land acknowledgments. They’ve become rote. What we need is intentionality and action.

JM: Has a kind of performativity taken over land acknowledgments?

DAR: Absolutely. There’s a great segment on the Baroness von Sketch Show. Someone’s giving a land acknowledgment before a play, and someone in the audience asks, “So…should we leave?” The speaker’s thrown off. Then the person asks, “Are we donating to the community?” The answer is no. “What about the bottled water proceeds?” “No, that goes to Nestlé.” It’s hilarious — and accurate.

Acknowledgments should be a commitment. With thought behind them. With real actions we’re going to take.

JM: I think fear prevents many of us from engaging in reconciliation. It’s easier to fall back on something rehearsed.

DAR: People hold back because they’re afraid of making mistakes. That’s human. But reconciliation is still new. In the grand scheme of Canada’s history, it’s only been about 15 years. Mistakes are part of growth.

We need to give ourselves grace to make mistakes. If you try with a good heart and mess up, that’s better than doing nothing. What I’ve found is that being open, honest and vulnerable builds relationships based on trust. And that’s what we need.

More on Broadview:

- This Cree-Métis lawyer is shaping law with trauma-informed practices

- Tanya Talaga’s new book is her most personal one yet

- Are controversial monuments making a comeback?

JM: Your book has many helpful ideas. Were there any that resonated deeply with you?

DAR: Many of the actions in the book are arts-based because I believe in story. Art is storytelling, and storytelling is the foundation of reconciliation. Even the last action, sharing, is about sharing music or literature that educates. Food is culture, too. Culinary arts are storytelling. Whatever the form, art saves lives. It can guide us.

“I can offer ideas, but you do the lifting, and we walk together.”

JM: You dedicate a couple of chapters to the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on Sept. 30. For you, this day is much more than just wearing an orange shirt. How can we live it in a meaningful way?

DAR: By making it more than a day. That’s the key. Honouring survivors is meaningful. But the danger is treating it like a one-day event. Like, “Okay, I’ve done the work.” We need to carry the spirit of that day into our daily lives. I’m not saying you have to devote your life to reconciliation. But live the sentiment in how you conduct yourself in [the] community. Every day is a chance to learn, to influence someone. So ask yourself: What kind of teacher do I want to be? What kind of learning do I want to do so I can become a better teacher? That’s what Sept. 30 should be — a starting point.

JM: What can teachers, librarians and parents do to help kids learn about the history of the residential school system in a responsible way?

DAR: I think the first thing to understand is that kids can handle a lot. They’re very intelligent, and in my experience, they’re capable of absorbing complex stories. When I wrote When We Were Alone, my picture book about residential schools, I didn’t shy away from the history. I approached it in a way that could generate empathy and understanding rather than fear or trauma. How would it feel to have your hair cut? To not see your family? To not be allowed to wear your favourite shirt or speak your language? Those are good starting points for young children.

What you want is to have these hard conversations in a way that’s right for their age. You’re building a foundation so that as kids get older, you can go deeper. It’s no different than how we teach anything else. You don’t start a first-grader with calculus — you begin with the basics. It’s the same with this history. You start with what’s relatable and build from there. By Grade 8, maybe it’s time to talk about the abuses that happened in the schools. Maybe it’s time to introduce terms like “genocide.” The conversation deepens as kids mature and become ready to engage with the really hard things.

JM: How do you view your role or responsibility in doing this work?

DAR: I’ve chosen to do this work as a writer, though I could easily write about lighter, more fun stories — and I’ve done that sometimes. But when you have the ability to create change, when you have a platform, I think you also have a responsibility to use it.

I do feel that, too often, Indigenous people are expected to provide answers to problems we didn’t create — even though we understand what needs to be done and how to do it well. There’s a balance to strike. Some people in our community can offer guidance, but it has to be a shared workload. This book is a starter’s guide to walking the path in a good way, but it asks you to do the work. I can offer ideas, but you do the lifting, and we walk together.

JM: You’ve said reconciliation is a long process. What gives you hope?

DAR: Kids give me hope. I have the privilege of speaking to kids across Canada almost every day, from all walks of life and all grade levels. Seeing what they’re focusing on gives me hope for the kind of leaders we’ll have: more informed, empathetic and active leaders who will make better decisions and lead us well.

I choose to see that hope rather than focus on setbacks. In work like this, it’s easy to get discouraged, but it’s also easy to be hopeful. How you choose to feel drives the work you do and the passion you bring to it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Julie McGonegal is a writer and editor in Guelph, Ont.

This interview first appeared in Broadview’s September/October 2025 issue with the title ”A Journey of Understanding.”