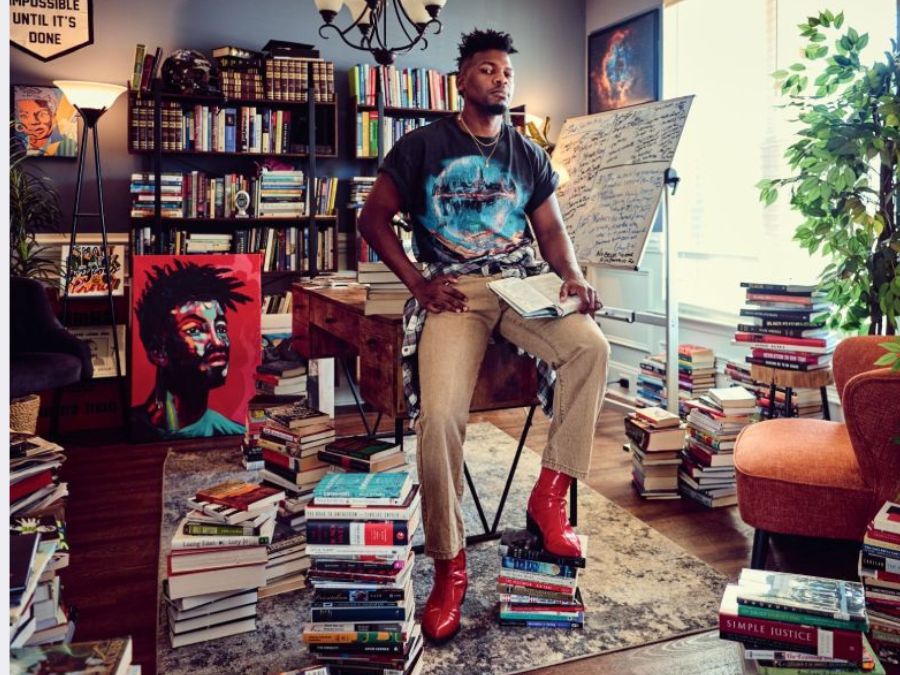

Christopher White: I’d never heard of Charlie Kirk before his assassination, but there has been an enormous reaction on the right and on the left to it, and you wrote a very thoughtful and challenging piece on it. You talked about the selective outrage that the United States has regarding some of the assassinations that have happened. Can you talk to me a little bit about that?

Danté Stewart: I think it can be characterized in a post that I saw the other day — how many people got fired for mocking George Floyd? Both Floyd and Kirk are citizens. None of them were government officials or anything like that. In the death of one, this country allows people to mock and to belittle and things like that, and then the death of the other, a person who built his whole platform on bigotry and hate and exclusionary politics and just flat-out cruelty, is treated like a saint. And I think the question that I’m always trying to ask is, what does this mean for us?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

It’s almost like an American Christian outrage, because Kirk sits at this intersection of religion and politics, particularly around conservatism and evangelical Christianity, where he merges both of those and benefits from both of those and exploits the worst impulses of both of those identities. And that’s all I really wanted to wrestle with, is that, if I can be honest, I find it very hard to mourn him. I’m not a person who’s going to cry any tears for him, but I will say, okay, let’s figure out what this means for all of us.

CW: I want to just get your take on the theology of Christian nationalism, which is very tied to this in the United States, and it has absolute echoes of Germany in the 1930s late 1930s. What do you see as the role of Christian nationalism right now in the United States? And we’re starting to see parts of that also popping up here.

DS: Let me say, first and foremost, there are scholars that are much more apt to talk about Christian nationalism than I am. I’m thinking of one in particular, Dr. Jemar Tisby, who’s an amazing scholar that people should follow.

But I think Christian nationalism, thinking about those on the American right, plays a central role for them. For many Christians in that tradition, which I was part of for about six or seven years while attending an evangelical church, the belief is often that America is a Christian nation. While they may not explicitly identify as Christian nationalists, they commonly assert that the nation should be guided by the principles of the Bible. Now, the problem with that is, is that in the Bible, there is no quote, unquote mandate that a nation should be a Christian nation. It’s my view that we’re not called to desire a Christian nation, but we should be people who are, in whatever country or nation state that we are in, trying to better that place and make it more loving, make it more just, make it more equal.

And I think for many people who are on the American right, religion is an ultimate thing, right? It’s their whole identity — there’s no place in which faith should not go. So if you think about bad actors in history, they have understood that if you can infuse churches and schools and areas like that with bad religion and bad theology, then you can control a mass of people who would think that these bad ideas and bad actions are a part of their devotion to God. That type of demographic is very vulnerable, because in some sense, their idea of faith, there really isn’t any openness to the possibility of being wrong.

More on Broadview:

- Toronto condo’s lawsuit against street ministry is deeply cruel

- Filmmaker captures untold stories of Black caregivers in Canada

- RFK Jr.’s views on autism aren’t just wrong — they’re dangerous

And I think this is not something new in Christianity. Christianity has always struggled with the tension of relating to people as if they’re fully human, as if they should be protected. What we’re seeing right now is like a kind of endgame with the merging of religion and politics, particularly conservative Christianity in America. I’m thinking of Julian Zelizer and Kevin Kruse’s book Fault Lines, where they talk about the history of the United States since the 1980s and one of the chapters in there talks about religion and this almost like play by play, where those on the American right understood something about using conservative Christianity as a way to institute bad policies, as a way to control, as a way to manipulate and things like that. And so for many of them, it’s central, because they believe that this moment is about a kind of God moment.

But there are those of us who are Christian as well, who are not Christian nationalists. We have to fight against it, but at the end of the day, I belong to Tabernacle Baptist Church, a historic black church in the town where I live. And every week isn’t about fighting against Christian nationalism, because if we’re only thinking about our faith as only about what we’re against, rather than the type of people we’ve become, then faith becomes limited. We kind of use the same script that we’re trying to fight against. So I think we need to address Christian nationalism, because it’s very powerful, and these people are actually having real-world consequences on very vulnerable people. And we need to be writing about it constantly and talking about it constantly. But also, I think for so many of us, our lives are bigger and we are much deeper, and we are much more worthy than the very small, limited, weak views of those who would desire a white Christian nation.

I’m reminded of Toni Morrison. She said, if you can only feel powerful when your foot is on somebody’s neck, then you have a serious problem. And then right after that quote, there’s a line, she says, white people have a serious problem.

CW: What would you say the call to the churches, and especially those in the former mainline, because our reality is that we are shrinking at the very time when I think the values that are represented by much of the former mainline church are desperately needed.

DS: On some level, I think it’s not the desire to have less faith but a better faith. I think sometimes in moments like this, it’s easy to say, okay, let me just throw out my faith because it’s associated with the worst kind of people. But I think there’s something generative and good about being a person of faith, and I don’t think that it’s fair for us to give them a monopoly on faith or the language of faith that we use as Christians.

I think that we should honestly evaluate it and question why this particular faith creates such bad Christians, and we need to ask those questions of how can we be different? And I think the second thing for me is that the only way to get through this is together. And I think there has to be a kind of humanity about us, where I really don’t care right now where you fall in what you say, if you have bad ideas, I want to convince you to have better ideas. But I also want to convince you to be a better kind of person for people.

We need each other, and we need to lean on the people and resources that we have around us. So it’s almost like loosen the grip on once-cherished ideas or identity and reach out to the people around you, even if they’re not people that you normally would have reached out to and lean on them, because God is at work in them as much as God is at work in you. And I think whenever we believe that God is only at work in our experience, then we limit ourselves to our experience of faith or goodness in the world.

But I also think we’ve got to say something. I’m thinking about Rev. Mariann [Edgar Budde], when President Trump was visiting the National Cathedral. She was willing to speak truth to power. Or even I think about Rev. Dr. Howard John Wesley in Virginia, who just preached a sermon. And many people around the country who preached sermons this week and for helping us try to wrestle with this moment, when it comes to people turning Charlie Kirk into a symbol of Christian goodness and mercy and compassion, when he was everything but that in this life. And I think calling a thing a thing in this moment, and being willing to like say something, even if it costs you. This is where the community comes in, so that it’s easier to say things and you don’t feel like you’re lonely.

CW: This is the first time, at least for the Canadian church, where there are going to be consequences for speaking out. And it’s a time that calls for courage. So my next question is, where do we find the courage?

DS: It has to come from within, and it has to come from one another. And I also think it has to come from history. So human beings, we’re a very, very resilient species. And when push comes to shove, we can do hard things.

So it’s like leaning on your own intuition and your own story and your own kind of guts to reach deep down, because we can do it. And we think about our lives, there have been micro-ways where we’ve done hard things, and I’m preaching to myself right here. Courage is very difficult. Maya Angelou says that without courage, none of the virtues can be practiced consistently. And I can see in myself where I lack courage in some real ways and I think that if we look back over our lives, we’ve been courageous, we can lean on that and say, okay, if I’ve done it before, then I can do it again. If I made a hard decision before, then I can do it again. I had a hard conversation before; I can do it again. If I’ve stood in the gap for somebody, then I can do it again.

This moment in American history is bad, but I’m Black. I come from people who were enslaved. I come from people who were sharecroppers. I come from people who, the little that we did have, it’s been taken from us. So I think that there’s a lot that people can learn from us in this moment, but I also think there’s a lot that people can learn from women. There’s a lot that people learn from black women. There’s a lot that people can learn from LGBTQ persons. And we think about these kinds of various aspects of oppression, there are things that we can learn from others that should challenge the way that we think and figure out, okay, how did they do it? And what can I lean on in their story to help me find the strength and the courage I need in my story?

***

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity. Watch the full interview here.

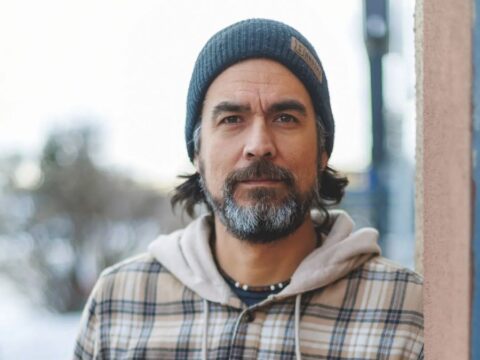

Rev. Christopher White is a United Church minister in Hamilton.