For a brief moment, refugee advocates thought that Canada got it right. Earlier this week, there were signals that the Canadian government, not unlike others around the world, was going to implement travel restrictions to help address the public health challenge caused by COVID-19. Wondering whether, and how, such restrictions would impact those seeking Canada’s protection by land or by air, we braced for what was to come.

But when the first set of travel restrictions were approved mid-week, the government’s Order In Council clarified that the measures would only apply to foreign nationals arriving by air, and a careful exemption was included so that “protected persons” (ie. people in refugee-like situations), could still gain entry to Canada.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Then, when Canada announced that there would be a tightening of the Canada-U.S. border, Minister of Public Safety Bill Blair stipulated that Canada would not bar irregular claimants from claiming protection in Canada. Yes, those who were entering Canada between regular points of entry would face quarantine for 14 days, much the same as other travellers arriving from abroad. That measure was supported by a public health rationale, and it appeared that the government was deliberately crafting its policies in a way that preserved refugee rights, our international legal obligations and public health.

More on Broadview: How a gift of land is helping Yazidi refugees farm again

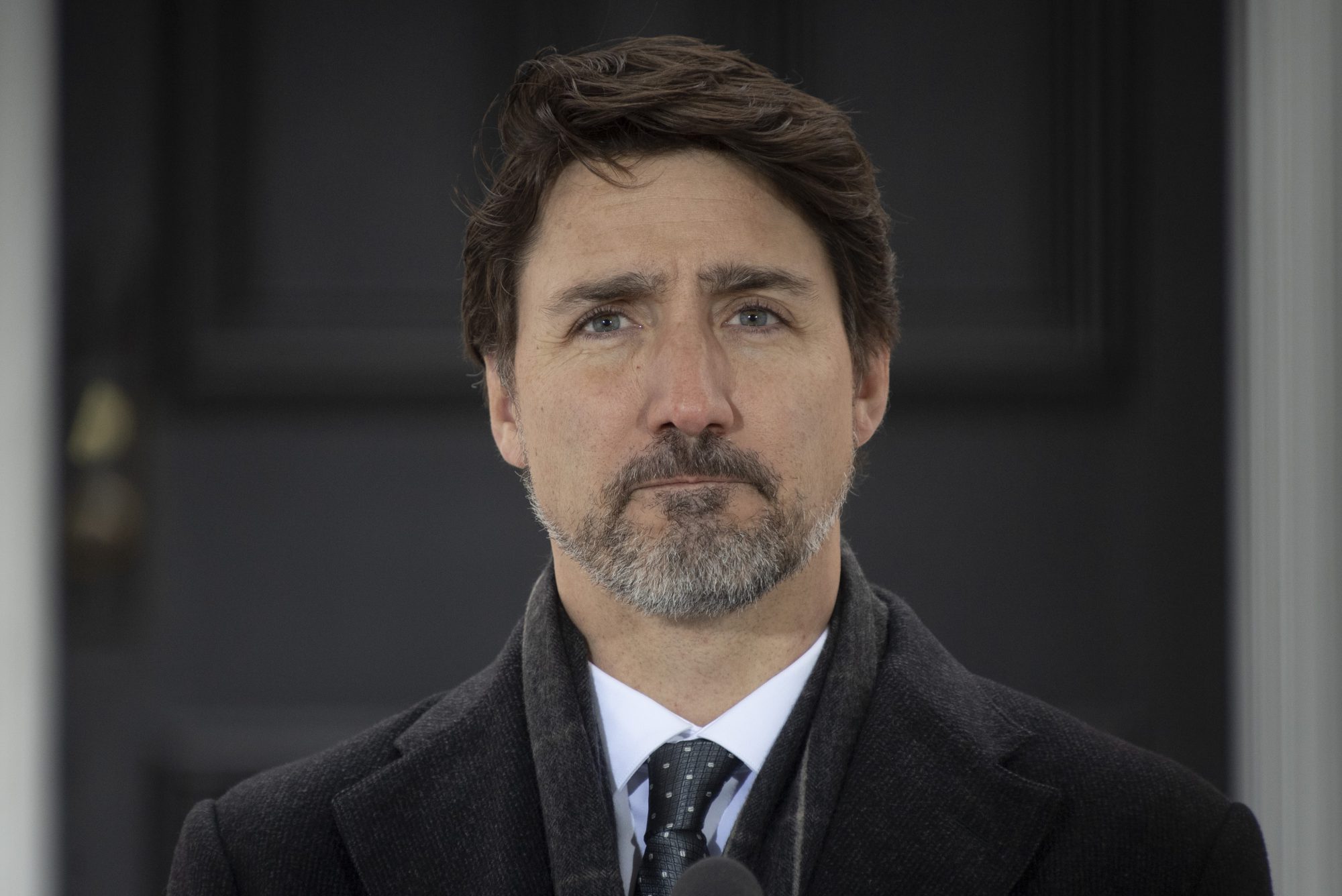

As it turns out, not so. In a stunning reversal, Canada now plans to block refugee protection claimants from entering the country. When I first learned of this about-face, I thought that a journalist had misunderstood and was reporting the story incorrectly, and that the error would be rectified soon. But after tuning in to Friday’s ministerial press conference, it quickly became apparent that the government had completely reversed its position. This is troubling for many reasons.

First, and perhaps most obviously, if there is one thing that can undermine public confidence at a time of crisis, it’s a flip-flop. Despite the rapidly involving situation around COVID-19, I can only imagine that most people seeing the news are wondering: what’s changed? We all know that COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate between citizens, permanent residents and refugee protection claimants. So, if the measures announced earlier in the week were evidence based (as we would expect), what explains Friday’s reversal? The press asked Blair this question, but he failed to provide an answer.

Second, it is entirely unclear from Friday’s announcement how Canada intends to implement this new measure. As the longest undefended border in the world, the practicalities of turning back those who are desperately searching for Canada’s protection is a Sisyphean task. The now well-established “unofficial” crossing at Roxham Road was a response to this very problem, and at least introduced some form of order into the “irregular” crossings. Its closure will do nothing more than force these people underground, through farmers’ fields, ditches, ravines and other places where they may enter Canada without detection by the authorities.

The Trump administration’s contempt for refugees knows no bounds, and the thought that anyone would give up on seeking Canada’s protection from Trump’s remain in Mexico policy, or being removed to Guatemala, Honduras or El Salvador under the so-called “safe” third country arrangements, defies all logic.

Finally, and perhaps more importantly, the measure is contrary to Canada’s obligations under international law, specifically the 1951 Refugee Convention. And, as if violating our international legal commitments wasn’t enough, by having taken this disproportionate measure at our land border, Canada loses all moral authority to encourage other countries to protect refugees displaced by war and conflict.

How, for example, will Bob Rae, who was only last week named as Canada’s new special envoy on humanitarian and refugee issues, convince other governments to put international human rights obligations at the heart of their responses to concerns about the consequences of COVID-19 for refugees within their countries? What authority does Canada have to press that point with countries faced with much larger refugee populations and far fewer resources, when we are not prepared to meet our obligations to the handful of people looking for Canada’s protection at the border?

In 30 days, the government’s Order In Council will expire and we could return to the status quo. Unfortunately, the stain on Canada’s reputation is sure to last much, much longer.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

I don’t have the answers, but…..

“if there is one thing that can undermine public confidence at a time of crisis, it’s a flip-flop.” – Under the circumstances I think most of the general public is thinking: “Let’s deal with the pressing matters at hand.” Those coming across the border can sit it out for a few weeks or months. (Those coming from the States are in a safe third country)

“Its closure will do nothing more than force these people underground, through farmers’ fields, ditches, ravines and other places where they may enter Canada without detection by the authorities.” News flash – this is already happening, we’ll deal with it as we have in the past, just more of it for now.

“violating our international legal commitments wasn’t enough, by having taken this disproportionate measure at our land border, Canada loses all moral authority to encourage other countries to protect refugees displaced by war and conflict.” – WHO has stated that ALL countries apply controls in a proportionate manner, allowing the flow of goods and services as well as essential services. I don’t think claiming refugee status fits either.

I’m thinking Canada’s reputation among the nations will never change one way or the other, in spite of our actions and circumstances.