It was the sound of a teenage girl’s voice on the radio that made Reina Carlson decide she wanted another child. But she didn’t want a baby. She wanted an older child, like the one who was pleading to be adopted on the open airwaves.

“I was sitting in the car with my husband and I turned to him and said, ‘I know we can do this,’” the Delta, B.C., resident remembers. “It was really pressing on my heart.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

That same month, November 2006, Carlson approached Sunrise Adoption, a private agency. She filled out the paperwork and completed the mandatory home study and police check. She and her husband, Robert, were deemed fit parents (they already have four biological children) and have been matched with a 14-year-old girl, though not the one from the radio ad. The Carlsons are now mentoring the girl — taking her for outings and introducing her to the rest of the family — before asking her to be their daughter.

“She might be apprehensive. I’m praying that at some point she will want us to adopt her,” Carlson says.

Though the girl might have trouble getting used to a new family, the Carlsons say they are ready for anything and that the experience has been positive so far. “It could possibly be an emotional roller-coaster,” says Carlson. “But we will take the challenges with the good times.”

If only more prospective parents wanted older children. Canada is home to 22,000 children over the age of three without homes and without families. Nearly 8,500 of these are in care and available for adoption. Many have special needs and most have endured rejection or neglect. In recent years, adoption agencies and provincial governments have gone to great lengths to find adoptive families, even resorting to media advertising to spark interest.

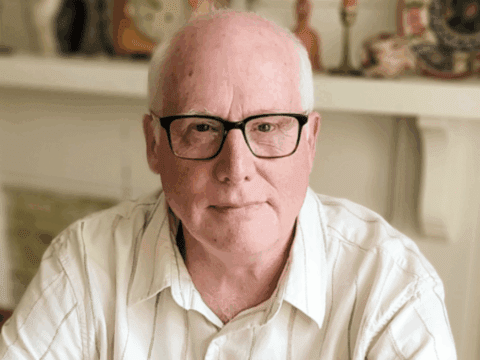

Rev. John Niles of St. Andrew’s United in Markham, Ont., is on a crusade to find a loving home for every waiting child in Canada and is spreading his message throughout the United Church and beyond. For 13 years, Niles and his wife, Liane, have been foster parents to nearly 1,100 kids and adoptive parents to one. They’ve seen it all: children who were “chewed on by pit bulls,” kids covered with scabies and others showing signs of abuse at the hands of their biological parents. Niles says older children often have tough exteriors but tender hearts that can only be nourished by a loving family.

“The first thought is that there are no children to adopt in Canada. That simply is not true,” Niles says on his way home from Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children with a four-pound baby boy being weaned off crack and heroin. “This child, whatever physical and mental problems he has faced and will face, is a child of God,” Niles says with conviction.

For Niles, finding homes for Canada’s foster children is a calling from God — one he hopes other Canadians will share. “Not only is it theologically correct, it’s ethically and morally important,” he says. “We have a responsibility as believers. We have all been adopted by Christ into the family and household of God.”

Niles is the author of three books about his foster parenting experiences, including The Art of Sacred Parenting and his most recent book, The Power of Positive Believing (both White Knight Books). In May 2005, he and Liane received awards of merit from the Governor General for their work with foster kids. Over the past five years, Niles has spoken at dozens of United churches in the Toronto area, as well as service clubs. This year, he launched a speaking tour on behalf of the Toronto Children’s Aid Society’s Homes for Kids program.

“My goal is to break people’s hearts so they open their homes,” the 45-year-old says frankly. “And I’m thankful that in every case, I’ve had people coming up to me saying that they’ve been trying to adopt but can’t because they don’t know where to start.”

“I tell as many people as possible about these children,” he says. “Every time we invite people over who would like to meet the children, they’re shocked. They often say, ‘Why wouldn’t anyone want these beautiful children?’”

At the Adoption Council of Canada, the Ottawa-based national umbrella organization that aids adoption efforts in Canada, Sarah Pederson co-ordinates a program called Canada’s Waiting Children, which finds homes for kids across the country. One prominent myth, she says, is that older children are permanently damaged and have no hope of becoming well adjusted. The reality, Pederson observes, is that emotional, mental and physical problems can be remedied with the stability of a good home.

“A lot of times these are issues that are no fault of the child’s. Just because they have issues now, it doesn’t mean it’s not something that can’t be worked through,” she says. And who’s to say a newborn child is a clean slate? “Both parents can be perfectly healthy, but there’s never a guarantee that the child is going to have a perfectly healthy life.”

ADOPTION EXCHANGES, events where parents meet with adoption agencies to learn about children waiting to be adopted, are one way agencies are trying to find homes for the growing number of parentless children. Sara Campbell of Forest, Ont., is the adoptive mother to Shelly, 13. She remembers attending an adoption exchange in Toronto where hundreds of adults gathered in a convention centre in hopes of spotting their perfect adoptive child among the endless pictures and videos of waiting kids.

“It was a room just full of prospective parents. The social workers showed a picture of a beautiful baby girl. You could see the parents lean forward on the edge of their seats,” Campbell recalls. “Then, the social worker said, ‘There’s just one thing. Both of the child’s parents have schizophrenia.’ You could just see everyone go, ‘Oh,’ and sink back in their seats.”

More controversially, the province of Alberta has been posting children’s photos and profiles on a website — a project that has helped it find homes for 30 percent more kids since its inception in 2003. The site is free for anyone to browse — a rarity among the more common screened and password-protected sites. Critics say this exposure threatens already vulnerable children who might be in danger of people from their past tracking them down.

But Anne Scully, manager of adoptions for the Alberta government, says the public access website is serving the children of Alberta well. “Now we have more older children being adopted,” she says. “It’s been a success because it’s easy to access information. We understand why other provinces have concerns, but some families become discouraged if it’s difficult to access the profiles of these children.”

Scully says the government checked with adoption experts before deciding to post the real first names of children and their photos online. Most other online adoption programs, such as British Columbia’s and Ontario’s, do not post photos with the child’s profiles. Those who do, including a national adoption program called Canada’s Waiting Child, screen prospective parents before they’re given permission to log in to the site.

To many adoption workers on the front lines, promotion and advertising are an acceptable means to an end. “You use whatever tools are at your disposal to secure a permanent place for a child,” says Kaushala Mahesan, an adoption worker with the Toronto Children’s Aid Society.

“The stakes are really high for these kids,” agrees Toronto CAS spokesperson Melanie Persaud. “When we talk to older kids, they tell us all they want is a home. If older children are saying this, we will do whatever it takes to get them adopted.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s March 2008 issue with the title “‘All they want is a home.’”