In my lifetime, I have gone from being a criminal if I bought a lottery ticket to being less than a patriotic Canadian if I don’t. Such has been the dramatic transformation in gambling laws in this country in the last half-century.

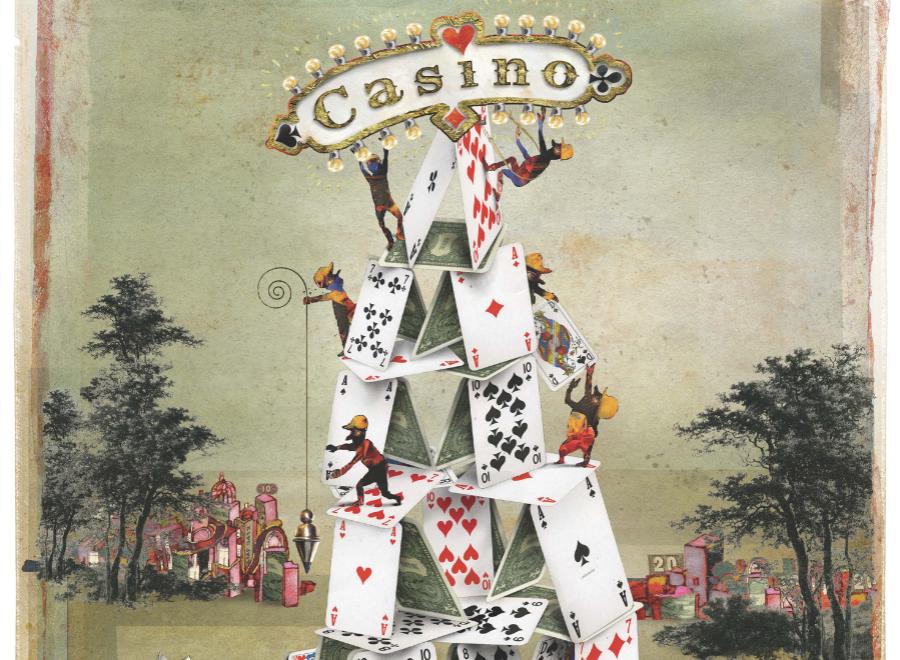

Yet not once, as far as I can recall, did any serious politician or political party campaign on a platform of more gambling. I could be wrong, but I’ll bet a sawbuck that I’m not. It happened by increments, and we all went along with it. Now, without any discussion of ethics or morality, our governments continue to push the envelope. It’s all economics and fear: apparently our civilization will founder unless we pay for our excesses by fleecing ourselves.

Politicians who supposedly represent us are bribing their own communities to widen the network of government gambling dens.

Is there a limit? Earlier this year, the citizens of Toronto seemed poised to live up to their old nickname of Toronto the Good. A powerful grassroots group strongly resisted a proposal by the aggressive Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation to establish a huge new casino complex in the city’s downtown. The city council eventually voted to kill the proposal.

Was this a backlash of public purity? Were we coming to our moral and ethical senses?

No. While some politicians rejected the proposal on its dubious merits, for most councillors, it was about the money.

Toronto wanted nothing less than $100 million a year as a fee for hosting the casino. The province offered $53.7 million, tops, so city council rejected the deal.

The casino clash illustrated a key point of modern politics: moral and ethical issues related to government-promoted gambling are rarely debated. There’s no shortage of evidence about the evils of gambling, but polls show that a majority of Canadians are still quite content with the concept. We’re glad to take a cut from a casino to lower our tax bills; just make sure you put it across town in the other guy’s backyard. Even then, resistance often crumbles if the pot is sweetened.

Rev. Cheri DiNovo, a United Church minister and the NDP member of provincial parliament representing Toronto’s Parkdale-High Park, was one of a handful of politicians who addressed the ethical issues related to the casino proposal. The casino, with all its temptations, would have been located within walking distance of one of the lowest-income areas of Toronto — an area that also has a higher-than-normal proportion of residents battling addiction and mental illness.

“Casinos promote addiction,” says DiNovo. “In a community like Parkdale where those with mental health and addiction issues are a loved and honoured part of the community, this can have devastating effects. Casinos are not glamorous. Folk gamble away life savings, grocery money and futures, and the house always wins eventually. God is love, according to 1st John. There is nothing loving about a crippling addiction or the costly devastation to our communities.”

DiNovo adds that casinos draw customers away from neighbourhood businesses, “because of both the lure of gambling itself and the incentives offered: free food and centralized shopping. This kills local business and promotes the empty-storefront phenomenon, slowing inner-city rejuvenation and investment.”

I remember visiting Canada’s first casino, on the seventh floor of the Fort Garry Hotel in Winnipeg. Imagining I would find a flashy betting house worthy of a James Bond film, I was surprised, shocked and saddened to discover that the casino was little more than a series of dreary hotel rooms stuffed with slot machines patronized by people who were clearly less fortunate than most.

Kingston, Ont., once rejected a casino. So it was built 30 kilometres away in the much smaller tourist town of Gananoque. When Kingstonians saw the $1.6 million in annual hosting fees the casino was adding to Gananoque’s coffers, some residents started a campaign to reclaim the casino for themselves.

The battle has produced some odd reasoning. Gananoque and its gambling partner, the Township of Leeds and the Thousand Islands, hired a consulting company to find out why Kingston would be a bad choice for a casino. The consultants concluded that “the demographics, the white-collar, higher-educated resident base of Kingston speaks to a community that does not welcome or align with optimal gambling populations.” Unlike Torontonians, the people of Gananoque are so enamoured of their gambling centre that they have started a Save Our Casino movement.

Simply put, the price is right.

But what price are we paying as a society when we use gambling proceeds to pay for essential services? Have we crossed some kind of Rubicon, led by our governments into untenable tax waters?

Once upon a time, gambling was banned in Canada, period. Subsequent amendments to the 1892 Criminal Code allowed local charities to run raffles, lotteries and bingos, but no big-time stuff.

The ascent (or descent, if you like) to massive government-encouraged gambling began with legal changes to stem the outflow of Canadian dollars into foreign lotteries such as the Irish Sweepstakes. In response to offshore gambling challenges and changing public attitudes, Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau announced in 1967 that Canada would loosen gambling laws.

In the meantime, the first lottery was already up and running. Desperate for cash to pay for the Montreal Olympics, Mayor Jean Drapeau came up with a scheme whereby people could buy a “voluntary tax” ticket for $2 and have a chance to win prizes worth up to $100,000.

Although the Quebec Court of Appeal ruled that his program was illegal, the popularity of it must have impressed the Quebec government. As soon as the federal government changed the law in 1969 to permit provincial lotteries, Quebec became the first province to organize one. The federal government chimed in with its own Olympic lottery to pay for the 1976 Games.

In less than 10 years, we moved from government-prohibited lotteries to government-promoted lotteries. At first, the money was used to finance non-essential but nice-to-have community projects, like hockey rinks and cultural centres. They were called charity lotteries, conveying the impression that all the money earned through gambling was going to good causes.

Today, lottery money is channelled directly into essential programs like health care and education. By playing up the benefits to these programs from gaming revenues, advertising soft-soaps us into believing that gambling is a harmless way of contributing to the community good. The subtle message is that if we don’t play, we are not only missing out on the fun but also shortchanging our neighbours.

After lotteries, the gambling action morphed into casinos. From that first one in the Fort Garry Hotel in 1989, we now have more than 100 casinos across Canada, including 16 centres run as partnerships between First Nations and provincial governments. And some provinces are getting into online gambling, encouraging gamblers to pay their voluntary taxes from the comfort of their homes.

Many churches, alarmed by the social negatives flowing from the gaming industry, are opposed to gambling. But not all are. The Bible itself does not condemn gambling, although it occasionally mentions the casting of lots in the same way we would talk about drawing straws or other ways of taking a chance. The United Church has stayed true to its Methodist roots by declaring gambling a social menace. The General Council opposes the expansion of gambling and urges congregations and church-related groups to refrain from using the proceeds of gambling for any of their projects. In the church’s view, gambling exploits the vulnerable, feeds addictions, increases economic inequality and reinforces a vision of a society made of “winners” and “losers.”

These are good moral and ethical arguments. But they have had little impact on government policy. Nobody mentions ethics anymore, so long as the price is right.

Orland French is a writer and publisher in Belleville, Ont., where he attends Eastminster United.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s September 2013 issue with the title “Government’s big gamble.”

Comments