As conflicts flare around the world, a beacon of hope shines in a small Canadian town. For two years, a group of volunteers in Bancroft, Ont., have been hosting community events and telling stories online to inspire and educate people about peace and the values that sustain it. Last September, the group announced they’d been given a two-storey, 8,000 square-foot property to establish a permanent home for the Canadian Peace Museum. The gift came from another grassroots organization, the North Hastings Community Trust, and represents the strong partnerships the museum group has built in a short time.

The museum is a registered charity, not a federal project, yet the group’s ambitions are national and their self-defined mandate encompasses a broad definition of peace. “When we speak about peace,” says museum co-founder Chris Houston, a former humanitarian aid worker in conflict zones, “we consider both negative peace: the absence of war, the absence of violence, the absence of fear; and positive peace: all the things that make for a more peaceful society. By that, I mean planetary health, human health, education, democracy, truth and reconciliation, art.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

It’s a grand vision for a new national cultural institution in a small town of only 4,000 residents. But Bancroft, which lies about halfway between Toronto and Ottawa, welcomes many visitors throughout the year, and organizers say the museum is well positioned to attract both domestic and international tourists.

Bancroft also illustrates Canada’s complex relationship with peace. Internationally, we’re known as a peaceful country. Prior to becoming prime minister in the 1960s, Lester B. Pearson proposed the modern concept of United Nations peacekeeping while serving as Canadian secretary of state for external affairs. He was given the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for his leadership in establishing the very first UN peacekeeping operation. In the years since, peacekeepers in blue berets have become an iconic international symbol.

But while Pearson was working for peace, prospectors were excited about uranium around Bancroft. During the Second World War, Canada had nationalized its uranium industry to supply the United States with raw material for nuclear weapons. Bancroft’s uranium was initially thought by government geologists to be too difficult to extract, but after the war, private companies were allowed back into the industry and established four mines in the Bancroft area. Though none of the mines are still producing uranium today, their cavernous tunnels deep beneath the soil remain an undeniable reminder of Canada’s part in developing the most violent weapons humanity has ever seen.

Rev. Svinda Heinrichs of St. Paul’s United Church in Bancroft participated in several of the museum group’s community events, including the unveiling of a peace pole, a type of monument found around the world with the words “May Peace Prevail on Earth” inscribed in multiple languages. She says the group is committed to the kind of social change and awareness that brings about a just peace. “Just peace happens when everybody regards and acknowledges that every other person has value and worth as a beloved child of our Creator,” Heinrichs says. “And that’s the problem with war, right? We make people less than, and that’s why we can kill them.”

More on Broadview:

- Forged Morrisseaus are hurting today’s Indigenous artists

- Why fascism fuels misogyny and how we can fight it

- Quebec’s struggling churches are finding new life as homeless shelters

Another organization supporting the museum is the Syria Civil Defense, also known as the White Helmets. Established in 2013, the White Helmets made international headlines for their volunteer work rescuing civilians from the rubble left by bombings during the Syrian Civil War. When the White Helmets became a direct target of the Assad regime, Canada participated in an international effort to help many of them escape the country. Once funding for transportation is raised, two ambulances formerly used by the White Helmets will be displayed at the museum.

“A museum like this becomes a beacon of awareness,” says Farouq Habib, group deputy general manager of the White Helmets. “By shining a light on ongoing challenges to peace — whether in Syria or elsewhere — it encourages thinkers, communities and policymakers to work together on solutions.”

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Canada is also vouching for the museum by loaning an exhibit by one of its contributing photographers, Nicolò Filippo Rosso. Called Exodus, the exhibit documents stories of loss and separation among migrants leaving their home countries in Latin America as they look for safety.

“Showing this exhibit in a Canadian museum offers a unique opportunity to bring the global refugee crisis into a local, human context,” says Darcy Knoll, senior communications officer at UNHCR Canada. “It also serves as a reminder that peace is not just the absence of war, but the presence of justice, dignity and compassion.”

The need for positive expressions of peace is unfortunately growing. The same month the museum announced the gift to establish a permanent home for the project, the Trump administration declared it was changing the name of the U.S. Department of Defense to the Department of War.

But the generations since the Second World War have shown us that aggression doesn’t have to define our national cultures. Museum co-founder Houston points out that conflicts aren’t necessarily driven by a desire to harm each other. Conflicts arise when people have run out of options to resolve things through other means, or because countries have leaders who think good leadership means being aggressive.

Houston suggests that using conflict to settle disagreements is a failure of imagination. “Our inability to speak to each other and to disagree,” he says, is an “oversimplification of society.”

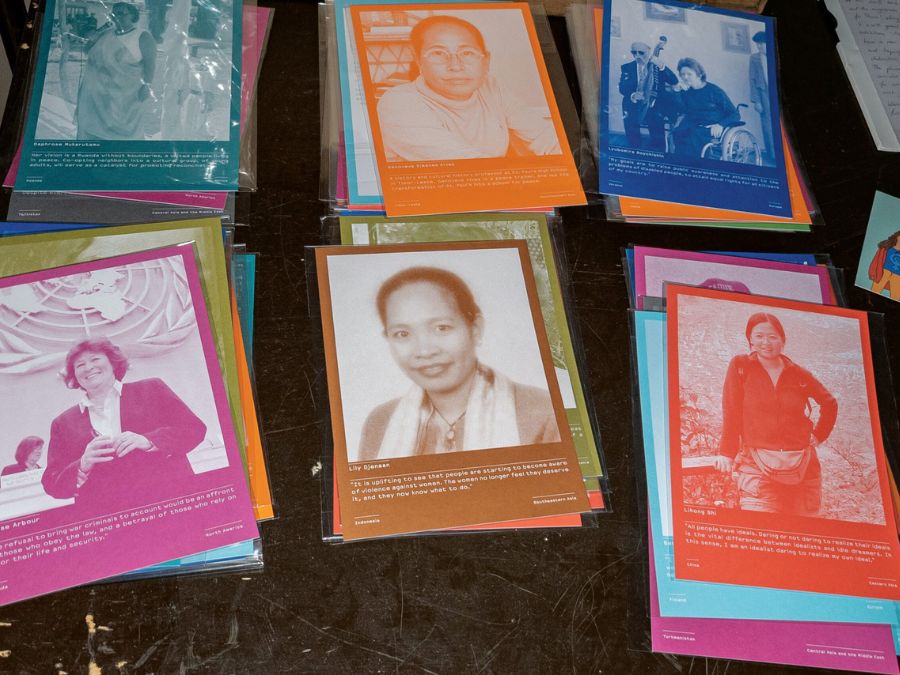

With renovations underway, the Canadian Peace Museum will open in phases as funding allows, beginning as early as this summer. Initial exhibits will include a timeline of the peace movement in Canada and displays on symbols of peace. The museum has also been loaned 1,000 Faces of Peace, a travelling exhibition featuring the portraits of 1,000 women peacemakers from around the world who were collectively nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2005.

The hope is that all the exhibits will spur conversations among Canadians, so we can speak more with our neighbours. “I don’t want people to just think this is about what’s happening in Sudan or Gaza,” says Houston. “This is not just a faraway thing. This is an us thing.”

This article first appeared in Broadview’s March/April 2026 issue with the title “Giving peace a chance.”

***

Angus MacCaull is a journalist and poet in Toronto.