The Kootenays in southeastern British Columbia evoke a sense of lush natural splendour. The fields, mountains and rivers that stretch from Castlegar past Creston are synonymous with bountiful crops and mineral-rich earth full of gold, copper and zinc. In October 2023, I drove the 620 kilometres from Vancouver to Castlegar, where the winding mountainous route snaked through roads dotted with old-growth western pine. The Ktunaxa First Nations, for whom the region is named, have lived here for more than 10,000 years. European fortune seekers scouring new lands for furs and minerals began arriving in the 1800s.

The region is also intimately intertwined with the Doukhobors, the pacifist Christian group that first sprang up in rural Russia in the 1700s. Persecuted by imperial Russia for their anti-war beliefs and rejection of the Russian Orthodox Church, the Doukhobors settled en masse in Canada at the end of the 19th century. An Orthodox archbishop labelled the group “Doukhobortsy,” which means “spirit wrestlers” in Russian — or those who struggle against the Holy Spirit. The group reclaimed the name to mean those who fight for, and alongside, God.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In Grand Forks, I passed the sites where Doukhobors planted tens of thousands of fruit trees and churned out caseloads of apple, plum and raspberry jam during the Great Depression. In Castlegar, I listened to the rush of the Kootenay River below my feet as I walked along the 100–metre-long Brilliant Bridge, hand-built by Doukhobors over a century ago. In town, I stayed at a 100-year-old red-brick Doukhobor home that once had 16 bedrooms and housed several families.

Canada initially offered a safe haven for the early Doukhobors. But government laws around private land ownership, compulsory public schooling and a taxpayer-funded military chafed against traditional Doukhobor values. Members’ differing ideas on the best way to live as Doukhobors, and as Canadians, soon led to internal rifts and disputes with the state that both splintered the community and pitted them against the government. Last February, the B.C. government apologized for taking Doukhobor children from their families and placing them in forced education facilities in the 1950s.

The Doukhobors’ 125-year-long history in Canada has been shaped by struggle — between members and against state-sanctioned war, materialism and cultural erasure. In recent decades, the Doukhobors have also contended with dwindling numbers as younger generations choose the comforts of urban life over traditional Doukhobor ways. This existential encounter with modernity has been compounded by the fallout from Russia’s war on Ukraine, alongside the scars from government policies that tore apart families. The community has now reached a critical juncture: some elders worry the group could cease to exist in a decade. But as the Doukhobors confront an uncertain road ahead, some say healing their past divisions could be the key to a better future.

***

In the winter of 1899, more than 2,000 Doukhobors boarded the steamship Lake Huron at the Black Sea port city of Batumi in Georgia, which was then part of the Russian empire. The ship, billowing black smoke and adorned with three tall masts, carried the first Doukhobors to Canada. They landed in Nova Scotia, then boarded trains to settle in western Canada. In all, about 7,500 Doukhobors arrived in Canada in a similar fashion that year. Russian writer Leo Tolstoy helped finance their journeys. He sympathized with the group’s principles of simplicity and pacifism and viewed Doukhobors as ahead of their time. Tolstoy called them “people of the 25th century.”

The Doukhobors had considered relocating to places as diverse as Cyprus, Texas, Hawaii and Manchuria. Canada at the time was looking for agriculturalists to settle its sparsely populated West. Its promise to the Doukhobors convinced them to move here: the government exempted them from military service and offered parcels of land where they could settle together.

Upon arriving in the Prairies, most Doukhobors began farming and living communally. But less than a decade later, backtracking on their original agreement to allow communal farming, the government seized tracts of undeveloped Doukhobor land and redistributed them to individual homesteaders. About 5,000 of the Doukhobor group then purchased and resettled large swathes of land in eastern British Columbia’s fertile valleys.

“They thought that when they landed in Canada they could live according to their own spiritual values, their own principles.…[But the government] had the colonizing strategies of shaping the Doukhobor settlers into good, compliant citizens,” says Ahna Berikoff, a Doukhobor and retired professor of child and youth care at Edmonton’s MacEwan University.

The Doukhobors’ move further west in 1908 allowed them to continue to live traditionally. It showcased their pioneering work in building residential homes and roads, transforming forests into thousands of acres of lush fruit orchards and berry fields. Some refer to it as their “golden age” in Canada — though it was not without conflict.

Competing attitudes about society, how to respond to the government and how to best live as Doukhobors split the community into three main factions that have defined modern Doukhobor life, says Jonathan Kalmakoff, 53, a lawyer and unofficial Doukhobor historian who grew up in Canora, Sask., a historic Doukhobor centre, and now lives in Regina.

Those who stayed behind in the Prairies farmed individual plots of land. They largely assimilated into broader Canadian life and are classified as independent Doukhobors. Orthodox Doukhobors, the largest branch, are affiliated with the Kootenays-based Union of Spiritual Communities of Christ (USCC) that serves as the Doukhobors’ formal organization.

In the early 1900s, a third and more austere Doukhobor group emerged: the Sons of Freedom. Their utopian vision rejected all forms of state interference, including government efforts to individually register land and enrol their children in public schools. Members adhered to a strict ascetic lifestyle and ate a vegetarian diet. They carried out non-violent naked demonstrations to protest materialism, first in the Prairies and later in British Columbia, where the splinter group relocated. The federal government eventually criminalized nude parading and in 1932 sent nearly 600 Sons of Freedom members to prison on a small B.C. island.

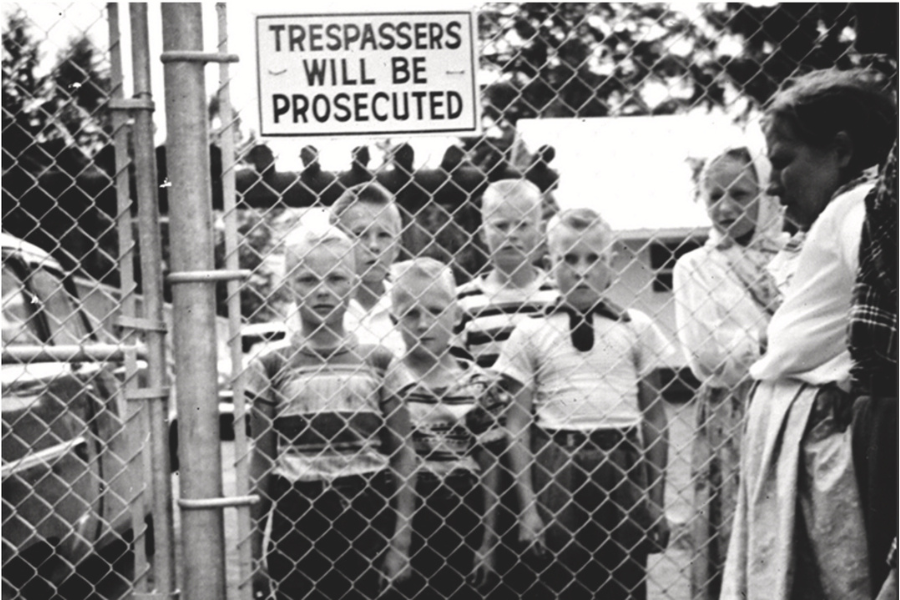

From the late 1930s to about 1980 in British Columbia, the Sons of Freedom bombed public structures like rail lines, courthouses and schools and burned down private property, including their own homes and Orthodox Doukhobor buildings and houses, to challenge increasingly heavy-handed government policies. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police raided Sons of Freedom homes in the 1950s and took custody of over 200 school-aged children in what they dubbed “Operation Snatch.”

Between 1953 and 1959, the children were forced to attend school in New Denver, B.C., living in a former tuberculosis sanitorium turned dormitory. Many endured physical, sexual and psychological abuse, with which the community is still grappling today. “It was an experiment gone awry,” says Berikoff. “It had a real detrimental effect on the children [and] families.”

Laura Savinkoff, a resident of Krestova, B.C., who died last spring at age 73, was raised in an Orthodox Doukhobor family. But she identified as a Sons of Freedom member, admiring their steadfast adherence to Doukhobor ideals. “The conversation wasn’t about cars, making money and getting ahead in life. It was about the principles and ideals of being a Doukhobor,” she said. When Savinkoff’s husband was a child, he was taken to the New Denver school. The pain he carried from that experience led to their marriage falling apart. “His trauma was getting deeper and deeper. I had to save myself,” she recalled.

The radical actions of the Sons of Freedom intensified the dividing lines within the Doukhobor community. Moderate Doukhobors viewed the bombings and burnings as contrary to the Doukhobor principle of non-violence. They also resented the negative media attention this extremism attracted. Many Canadians associated all Doukhobors with the actions of the Sons of Freedom, leading to further isolation of the entire Doukhobor community from Canadian society.

Berikoff, who identifies as a Sons of Freedom Doukhobor, says her mother and grandfather were jailed for their activism. She says the group is still contending with harmful stereotypes and the “long-standing effect of being represented in a sensationalist manner.” Among the community as a whole, “there’s deep-seated hurt from our history.”

***

As I walked from the parking lot to the Brilliant Cultural Centre on a drizzly Wednesday morning in October 2023, the sweet scent of freshly baked bread wafted from its doors.

Inside the centre — a USCC-run Doukhobor gathering place for everything from prayers and choir practice to meetings, weddings and funerals — a group of eight volunteers kneaded pillowy rounds of dough and carted the risen loaves off to industrial ovens. Bread, salt and water are omnipresent on Doukhobor tables, representing their core tenets of peace, hospitality and a simple life. The activity, which brought Doukhobor and non-Doukhobor volunteers together, also exemplifies recent efforts to engage with the wider community, says Michael Davidoff, 67, a lifelong Doukhobor who led the bread-making day. As the dough baked into golden loaves of rye and speckled whole wheat bread, he explained: Doukhobors believe “God is basically love…and that God and love potentially dwells in every person,” rather than in any formal institution, organization or book.

Davidoff’s childhood in the Chernoff village south of Castlegar typified traditional Doukhobor life. His family lived in a two-bedroom log home with an outdoor toilet and bathhouse. At the time, three other Doukhobor families resided in Chernoff along with his own. “One of the buildings served as a community hall [and] upstairs was a Russian school. I never knew how to speak English until Grade 1. I had very little. We lived a very simple life.…The value of having God and love is a more important thing than any material wealth.”

His generation would be the last to live traditionally. Communal living and farming receded from Doukhobor life as the effects of the Great Depression, government pressure, intra-community strains and technological change compelled Doukhobors to adapt and blend in.

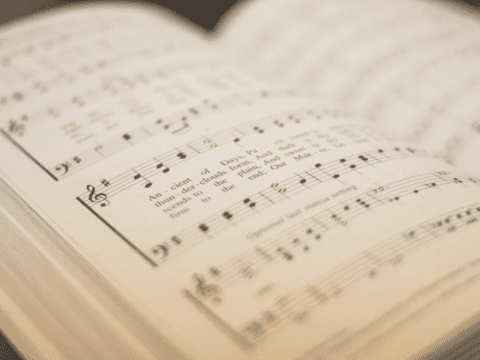

Some Doukhobor traditions have endured. After Davidoff’s volunteers packed up their aprons that rainy October day, a group of Doukhobor men and women gathered in the cultural centre’s fluorescent-lit, wood-panelled basement. They filled the room with an ethereal energy as they harmonized in melodic Russian to hymns that praised God and told of Doukhobor joys and sadness. Performed without musical instruments and written arrangements, a cappella singing remains vital to Doukhobor identity and oral history. Choir practice was “the popular thing in our day,” says Ernie Verigin, who teaches Russian and helps lead the choir in Castlegar. Among his generation, kids “couldn’t wait to turn 16,” at which age they could join the youth choir.

A few kilometres away at the Doukhobor Discovery Centre, an interactive musem of Doukhobor history, a handful of Doukhobor women peeled, chopped and brined a rainbow-coloured assortment of beets, potatoes, carrots and celery. The fruits of their efforts rested nearby on a long wooden table lined with glass jars of cherry-red borscht and pickled vegetables that would be sold to raise funds for USCC activities.

The Doukhobors’ community calendar is bustling. In any given week, groups of Doukhobors meet at community halls, local schools and members’ homes for traditional activities like woodworking, handicraft making and Sunday prayer service known as “moleniya.” They gather for special events such as borscht cook-offs and memorial services for past leaders, and to mark annual events from Earth Day to Human Rights Day.

Yet one key ingredient is missing: “Where are the young people?” asks Kalmakoff. He says there’s a lack of continuity involving Doukhobor youth — and he counts youth as everyone from 15 to 50 years old. “The majority of [the] active population is 65-plus,” he says.

The post-war decades in Canada ushered in a new era of assimilation and geographical dispersion that saw the number of self-identified Doukhobors plummet. Today, Canada is home to an estimated 30,000 people of Doukhobor descent. Yet only 1,675 Canadians self-identified as Doukhobors in Canada’s 2021 census — a 90 percent drop from the 1941 peak.

In Pelly, Sask., a village of less than 300 known for its vast wheat fields and historic sites — the Hudson’s Bay Company once operated a bustling fort here — retired farmers Fred and Eileen Konkin spend their summer days giving tours at the National Doukhobor Heritage Village, a “living museum” that recreates a traditional Doukhobor settlement of communal homes, a prayer house and more. They hope to share Doukhobor history and philosophy, which is “almost impossible to pass on [and is] getting lost. We took things for granted,” says Fred. Born and raised in Pelly, the Konkins remember growing up at a time when Doukhobor civilization was abundant. Now, “our numbers have dwindled so much at Sunday meetings, we’re wondering how much longer we can keep this up,” says Fred.

More on Broadview:

Communities traditionally populated by Doukhobors have emptied out as working-age people moved to more economically vibrant areas for education and job opportunities. The Kootenays’ unemployment rate has consistently trended higher than the provincial rate. “There’s no work here,” said Savinkoff. “For higher education, [young people] have to leave the community, so very few actually come back.”

Meanwhile, prayers and choir practice have been overshadowed by modern preoccupations like social media, shopping and logging long hours at school and work. Today, young people of Doukhobor descent largely “adhere to modern, secular life. They don’t speak Russian or go to prayers,” Kalmakoff says. He and his wife are raising their three children in accordance with Doukhobor values and beliefs. But living in Regina, apart from larger Doukhobor communities, means their children only see and experience the superficial trappings of being Doukhobor, like eating traditional meals of borscht, vareniki (crescent-shaped dumplings) and hand pies, Kalmakoff says.

For the Konkins, who raised their two daughters in the 1970s and ’80s, family life was busy with farm work and second jobs. “Our children attended services but don’t remember much. We didn’t sit them down for Doukhobor lectures, didn’t place enough importance on passing on the [Russian] language. As they got older, our kids developed their own ideas, which they passed on to their kids,” says Eileen.

Doukhobors, who historically don’t proselytize, have increasingly married partners from different religious, cultural and ethnic backgrounds — a trend most say is intensifying. Davidoff’s parents disapproved of him marrying someone from outside the Doukhobor faith. His grandson was recently baptized in the Roman Catholic Church, which he sees as growth. “The bottom line is that…we don’t have these closed doors,” Davidoff says. “[We’re] expanding our family with the same feelings and the same philosophy.” There are no steadfast rules to be a Doukhobor, he adds. “[We] have the spirit of God within us. We have the spirit of love — that’s all [being a] Doukhobor is.”

The community has felt the absence of young people acutely. District leaders have aged out with no successors to take over. Some local Doukhobor chapters have shuttered in the last half-decade.

There are signs of hope. The community has made recent efforts to attract younger members back to the fold, though long-term solutions remain unclear. “We need to do something different…to turn the tide. Because whatever we’re doing now, it’s not working,” says Kalmakoff.

Some are optimistic that an English-led revitalization of Doukhobor services and online offerings will engage young people. Ryan Dutchak, the 33-year old director of Castlegar’s Doukhobor Discovery Centre, is among those advocating for English prayer services and events, which some members have resisted in a bid to preserve Doukhobor Russian. “I don’t know if it’s necessarily foolproof, but maybe switching to or adding more English would be something that would attract more youth,” he says. Elders tell him, “I don’t want to come to an empty prayer home in 15 years.”

Active members are also finding new, digital ways to help people tap into Doukhobor history and culture. Krestova-based Berikoff is creating a video series on the early Doukhobors in the Russian empire and how they came to Canada. The project aims to help people understand the Doukhobors through bite-size videos rather than a 200-page history book, she says.

Last January, the USCC launched an in-person and Zoom speaker series on the teachings of Peter “Lordly” Vasilievich Verigin, an early Doukhobor leader in Canada who died when a bomb ripped through his train cart in 1924. (Some speculate he was assassinated, but his death remains unsolved.) The first session exceeded 100 participants on Zoom alone.

A handful of young Doukhobors are revamping Doukhobor websites — many of which were last updated in the early 2000s. Others are running Facebook pages or broadcasting YouTube and TikTok videos on Doukhobor life. The TikTok account of the Doukhobor Dugout House, for example, a national historic site near Blaine Lake, Sask., has almost 13,000 likes.

***

On an overcast afternoon in fall 2023, I followed the forestgreen hatchback of J.J. Verigin, the 68-year-old current leader of the USCC, up a gravel road to the Verigin Memorial Park. His father, grandmother and ancestors, including Peter “Lordly” Verigin, are buried at the site, which the Sons of Freedom bombed several times.

Verigin, clad in a dark grey suit — he had attended a Doukhobor funeral that morning — animatedly recalled his younger years when he and his Doukhobor peers were fiercely active in global peace movements. In 1991, after Boris Yeltsin became president of the newly formed Russian Federation, Verigin says Ottawa called on him and the USCC to give Yeltsin a tour of Vancouver. “They called us because they knew that we didn’t change course depending on which way the wind blew. We were always against war. We were never patriots,” Verigin says.

Doukhobors have long campaigned against war and militarism. The mass burning of weapons in 1895 by Doukhobors in southern Russia led to their exile from the empire and triggered their move to Canada. The crux of Doukhobor philosophy centres on pacifism — the belief that all violence, under any circumstances, is indefensible and unjustified. But being a pacifist doesn’t mean you can’t be courageous, Verigin says.

Riled up by the impending U.S. invasion of Iraq, Savinkoff in 2002 founded the Boundary Peace Initiative (BPI), a largely Doukhobor-run group that organizes peace rallies across the Kootenays. In Grand Forks last March, it hosted a free public event on the Israel-Hamas conflict that included Palestinian voices alongside Jewish anti-war activists, as well as a lunch of borscht. The BPI is now searching for an individual to take over from Savinkoff after she died unexpectedly just a week after the event. But fresh leadership might be hard to find. In 2023, Savinkoff sent out a request for help in distributing the group’s printed newsletter, which circulates to cafés and stores in the region. Only one 90-year-old man responded.

Before her death, Savinkoff lamented the absence of younger Doukhobors in building peace movements. “We don’t see them coming out to peace marches anymore. We’re lacking that vital generation’s participation in and leadership of the community,” she said.

Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine has divided the community even further. Most members agree with the USCC’s official stance that Doukhobors are, as Verigin puts it, “against all wars and violence. There are no winners in war,” and Doukhobors shouldn’t take sides.

Even so, Canadian Doukhobors remain fractured on how they believe their community should respond to Russia’s war on its neighbour. Doukhobors have ties to both Russia and Ukraine, and many have loved ones living in both countries. “Our people have been exiled to Georgia, Ukraine and the southern Caucausus,” Verigin says. Doukhobors’ ancestral history coupled with their diverse backgrounds today makes consensus difficult. Some resist the polarization of “pro-Ukraine” or “pro-Russia” stances and argue that the West has played a role in igniting the conflict. Others stand on Ukraine’s side and see President Vladimir Putin’s Russia as the oppressor. Most others refrain from talking about the subject. “We don’t have those kind of conversations…as a collective,” Berikoff says.

Doukhobors were ostracized for their Russian heritage when the war first began. J.J. Verigin says some stores and restaurants in the Kootenays refused entry and service to Doukhobors. Savinkoff’s elementary school-aged granddaughter told her that after she presented a class project on Doukhobor history, her classmates said being Russian made her inherently bad. The association with both the Sons of Freedom and with Russian aggression has led some members to pull away from Doukhobor culture. “People don’t want to get involved. They’d rather fit in instead,” Savinkoff said.

Still, a handful contend that Doukhobors can help Canada’s Russian and Ukrainian communities work together toward peace. Museum director Dutchak, whose family identifies as both Ukrainian and Russian, says Doukhobors and Ukrainians each faced the similar plight of fleeing Russian government oppression. Doukhobors, he suggests, “should be at the forefront of anti-war and anti-racism movements in Canada.”

For Dutchak, a resolution to the conflict is simple. “I’m not going to sit here and say I don’t take either side,” he says. “If Russia just would go back to Russia and leave Ukraine, then there’s no war.”

***

Last February, B.C. Premier David Eby delivered a solemn apology to Doukhobors at the provincial legislature in Victoria. He formally acknowledged the past actions of the B.C. government that forcibly removed Sons of Freedom children from homes and placed them in residential schooling, causing “harms that have echoed for generations.” The premier added that the province recognized “the stigma and trauma experienced by the Sons of Freedom and the broader Doukhobor community.”

Reconciliation — both within the community and with wider Canadian society — remains top of mind for many Doukhobors, who say that it’s necessary to move forward and to grow. The apology came with a $10-million funding package that will help preserve Doukhobor heritage sites, support cultural offerings and directly compensate survivors of the New Denver school and their descendants. Savinkoff said she cried for two days after the apology. “I hope this can be a catalyst for so much more, a deeper understanding of each other, and an acceptance and working together for a better world.”

Doukhobors are now taking inspiration from, and finding common ground, with Indigenous communities. Early Doukhobor settlers displaced Indigenous communities. But Verigin emphasizes that to survive their first winter in Canada, Doukhobors “were helped by Indigenous Peoples on the Prairies. We’ve always had a historical relationship with our Indigenous brothers and sisters.” In 1989, when the Sinixt people returned to Vallican in the Kootenays to protect their sacred burial grounds from a highway project, Doukhobors supported them with food and clothing and joined their protests asserting the Sinixt claim to the site, Berikoff says. “Now there are yearly events [and] initiatives that bring [together] Doukhobors and Indigenous communities in that area.”

The USCC has made reconciling with Indigenous communities a priority. Last fall, it partnered with Selkirk College’s Mir Centre for Peace to invite Cree and Lakota children’s author Monique Gray Smith to share her personal truth and reconciliation journey at the Doukhobor cultural centre in Castlegar. Doukhobor attendees filled the hall.

Doris Sookaveiff, a 79-year-old Castlegar-based retiree, is among those who believe Doukhobors have much to learn from Indigenous communities. “[They] are an inspiration in many ways. Seeing their young people taking interest in and relearning their ancestral customs is amazing. We have been slacking off on our own culture, which takes effort and time to uphold,” she says.

Much of the continuation of the Doukhobor legacy now seems to rest with individual families and the values and history that are passed down to children. And reconciling their own community could start with the younger generations. “When we become Doukhobors first — not USCC, not independent, not Sons of Freedom, not inactive — when we become Doukhobors, period, then we have a chance of preserving what our ancestors envisioned,” Savinkoff reflected. “My children’s generation will move it forward. But my grandchildren…all those divisions don’t mean a thing to them.”

***

Yvonne Lau is a journalist in Vancouver who writes about issues related to China and Russia.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2025 issue with the title “Wrestling with Modernity.”

Good report.